1. A note on the Yugoslav gender regime

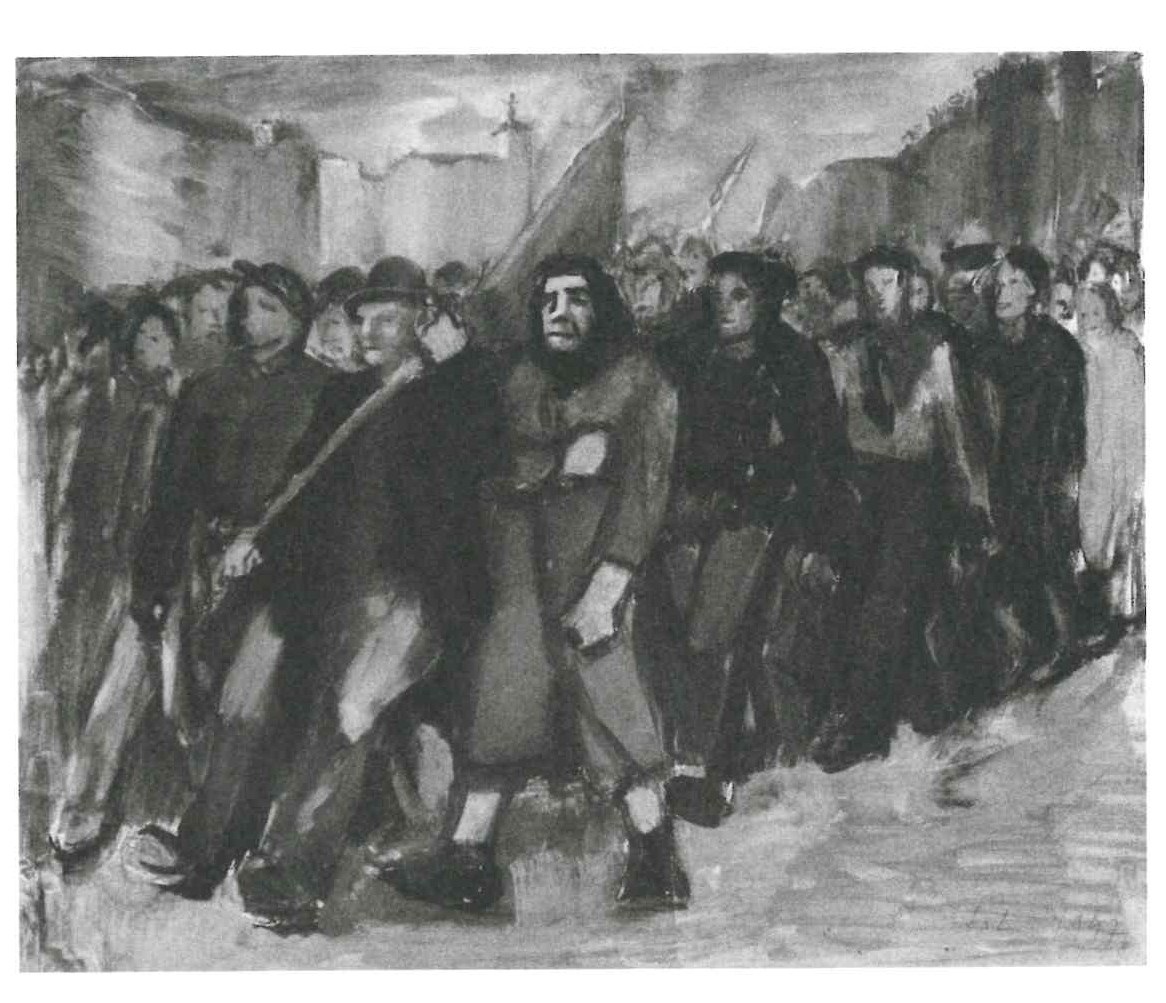

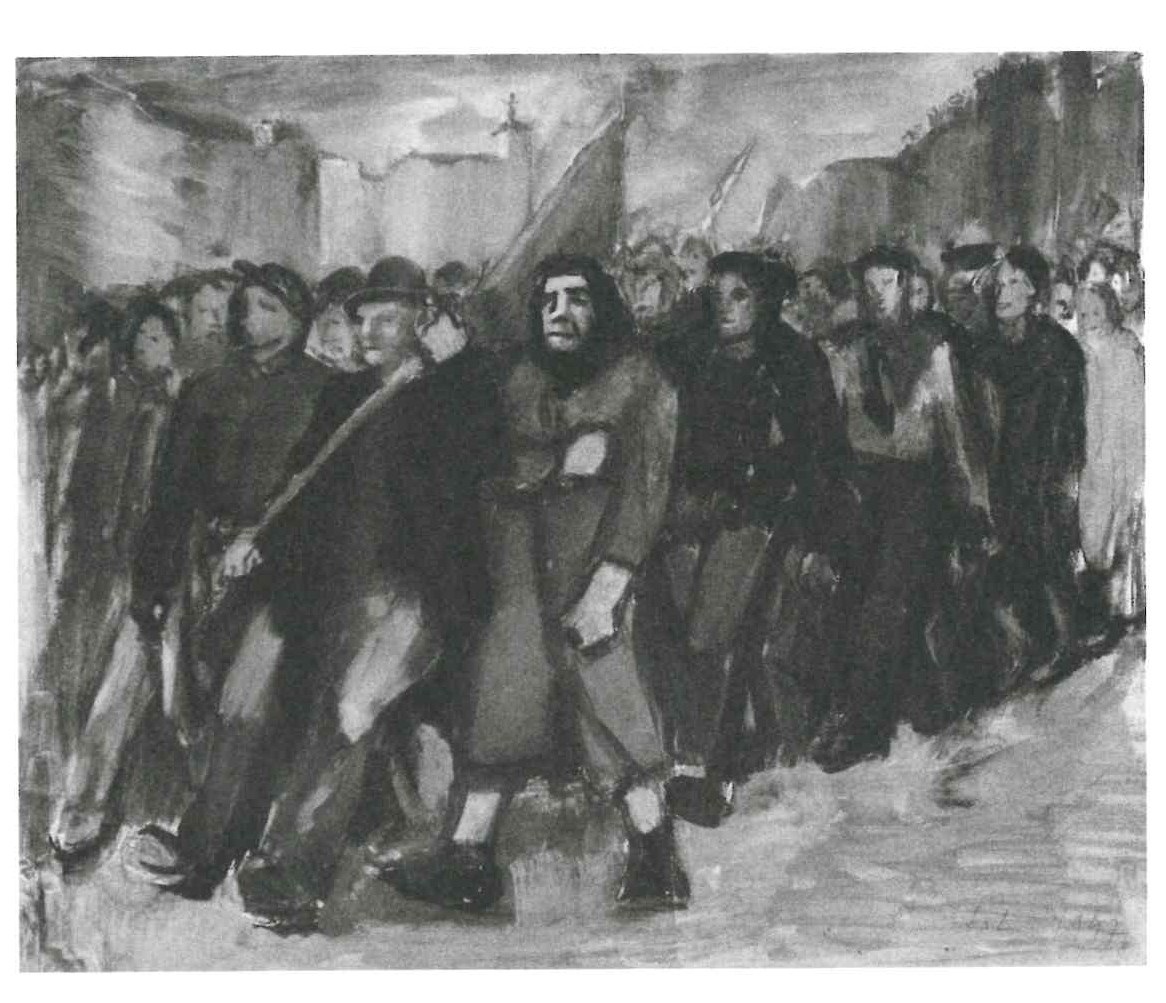

Picture 1. Stjepan Lahovski; Demonstration (Self-portrait as a female comrade in a procession), 1947.

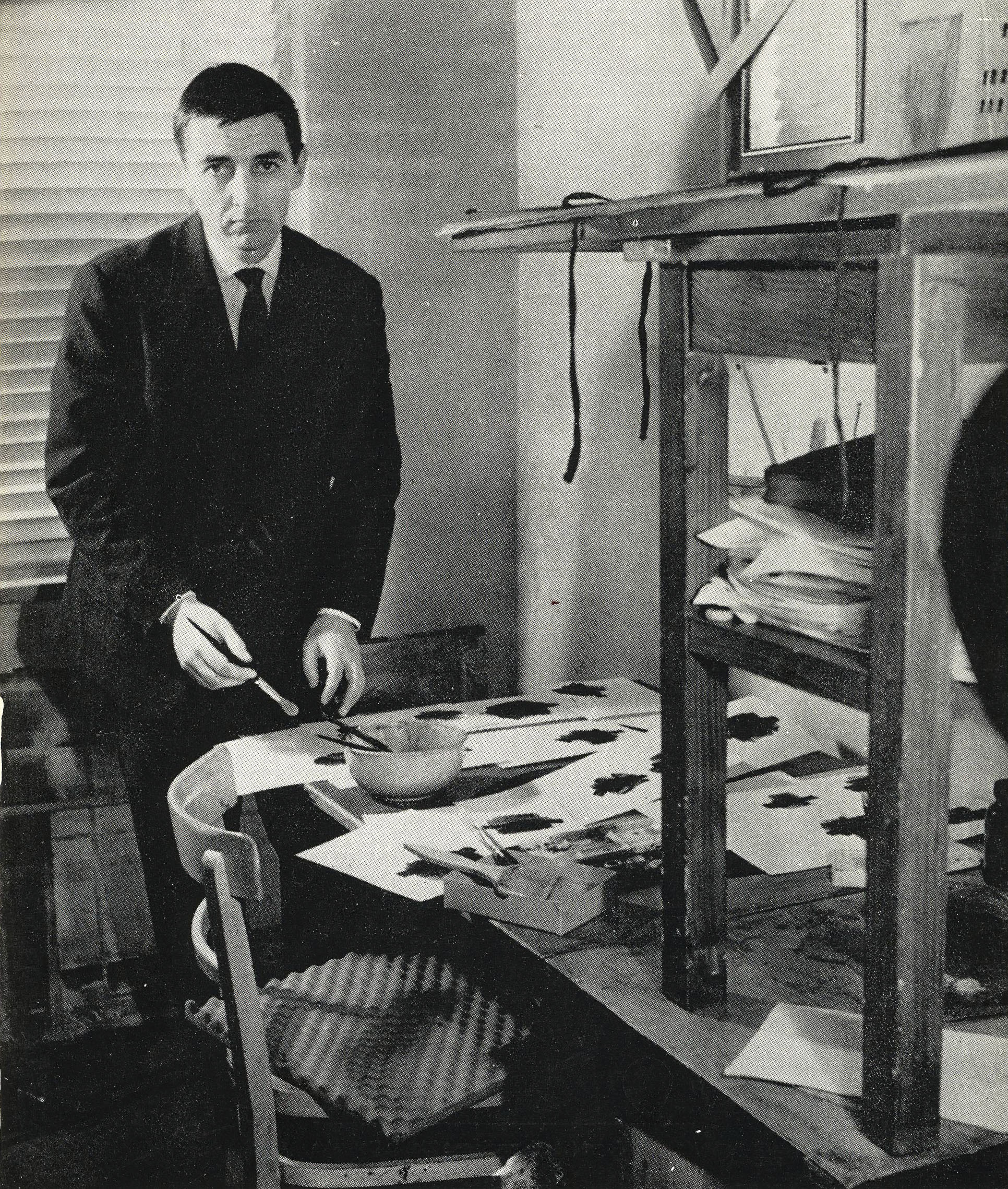

In 1947, painter Stjepan Lahovski painted a self-portrait in gouache under the title Demonstration – Self-portrait as a comrade in a procession (Ilustration 1). He said, “That’s me, an old woman (baba)1 in an overcoat, a headscarf and military boots.” The author, who throughout his opus was involved in making self-portraits painted in different styles and techniques, taking over “the vesture of a certain historical style”, thought of himself as not being courageous and not having a sense for struggles and wars. Thus, in various self-portraits he sought to compensate for some qualities he did not have, such as youth and courage. Why then he portrays himself like an old woman in a scarf? Although his statement accompanying the picture can be understood as a mocking of old women participants of demonstrations, the painting still tells a lot about the models of depicting courage in that period. In addition to the famous heroic depictions of female Partisan as some kind of Amazons with guns in their hands, the depictions of women during the period of the People’s Liberation Struggle, as well as in the postwar period, included also images of old women with headscarves depicted as they learn to write, as they participate in elections and perform hard physical work, as we can see in the numerous illustrations in the Woman in the Struggle magazine2 (Ilustations 2, 3, 4). In its editorials, this magazine explicitly expressed the goal of creating and disseminating new models of femininity, which is in line with the very reason for the emergence of this “organ of the struggle”.

After the war, the position of women was more drastically changed than that of men, creating the need for a more precise creation of the character(s) of “new” women in order to consolidate them to the right place in the new society. The Partisan is not only an Amazon or a Spartan, but bent and stiff. However, persistent, hard working and brave. The figures of heroes and heroines aimed to be associated with an ethic of hard work, and gradually the heroism of work became the most prominent social value that replaced the heroism of the struggle. In the imagery of that time, women appear as heroes of socialist work, women in peasant cooperatives, women cutting the woods or working on afforestation. Although the organizers of the Anti-Fascist Front of Women (AFŽ) were mostly educated urban women, and among the “ordinary” fighters were women from the towns, the heroines represented were almost always as villagers, often shepherds. Besides the fact that this contrast (nescient villager oppressed by rural patriarchal relations→strong, emancipated fighter dedicated to the building of a new society) more explicitly emphasizes the transformative effect of the participation in the People’s Liberation Struggle, the character of an illiterate shepherd or an old woman makes the woman a kind of tabula rasa in which it is easier to incribe any desirable meaning. On the other hand, the urban intellectual differs much more from the traditional ideal of womanhood, and it can also bear associations of bourgeois habits, values and lifestyles typical of the urban middle class from which she probably originates. By using the figure of a female comrade in a military overcoat and a headscarf for a self-portrait, Lahovski does two things: 1) he clears himself of his “negative” attributes – bourgeois lifestyle, cowardice, inadequate masculinity, “homosexuality” and the decadence and laziness associated with it3; and 2) shows that certain characters of the new woman – Partisans and heroines of labour – have in some way become iconic – symbols of certain values for the depiction of which certain recognizable models were always used. The fact that Lahovski somewhat ironically appropriates such a representation of women for the exploration of his own identity, already in 1947 suggests that the figure of the heroin of labour would quickly become emptied of its content.

Continue reading →