Nina Simonović

1.

In the not-so-inspiring imagination of the post-Yugoslav Yugonostalgic left, a specific style of writing about “socialist” Yugoslavia persists, one that entails the use of a specific vocabulary. This vocabulary is dominated by ideological constructs that always emphasize the supposedly “contradictory” character of the Yugoslav society, such as: “complex class logics that collided and confronted each other”; “contradictory political and economic phenomena”; “social dynamic that was simultaneously centripetal and centrifugal” and so on.

In this sense, the publication “Gradove smo vam podigli” (“We Raised Cities for You”) is characteristic (the subtitle is “On the Contradictions of Yugoslav Socialism”), recently published in Belgrade, as supplementary material for an exhibition of the same name. In fact, all of the above-mentioned ideological phrases are taken out of the introductory text from this publication. Along with this text, I will also briefly take into account the text “Contradictory Reproduction of Socialist Yugoslavia” from the same publication. This exhibition and publication gathered a number of leftists from the Yugoslav area and represent a very good and fresh example of the ideological articulation of this type.

In the mentioned introductory text we also encounter the ascertainment that a “socialist revolution led by a communist party” took place in Yugoslavia, that this was “an emancipatory endeavor (…) that spread itself through the ideas of self-management, structurally democratic participation in the political life, social ownership of the means of production…” and it is stated that in this period “Yugoslavia for the first time in its history secured a real independence in relation to the global dynamics of the political and economic centers of power.”[1]

Besides this, there are statements about the consequences of the breakdown of Yugoslavia, so we can read “that all of the states created after the destruction of Yugoslavia are nationalistic and capitalist” and that the agendas of local regimes are submitted “exclusively to the logic of capital.” The expressed sorrow seems especially painful because today “the interests of the working class are represented by hardly anyone,” and because the lack of “educational and socio-political activities directed at the workers” and again the lamentation for the absence “political representation of the workers.” This post-Yugoslav period is always, and self-evidently, characterized as the “restoration of the capitalist system.”

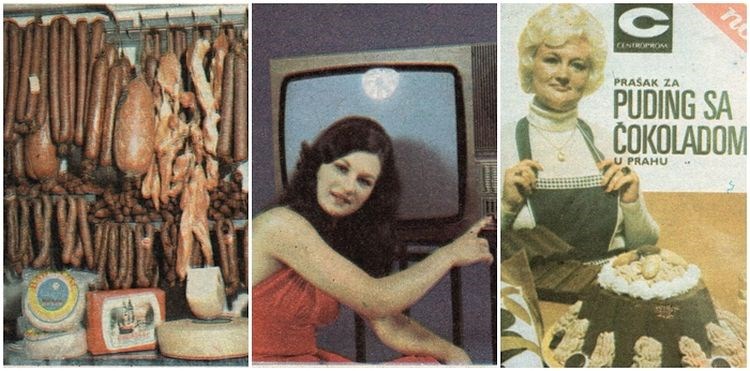

To put these ideological phrases in question you don’t have to look far away. It is sufficient, for example, to look at the text “Contradictory Reproduction of Socialist Yugoslavia” from the same publication. The authors of this text strived to write a balanced text that would, as they explicitly state, avoid the trappings of, on the one hand, approaches that portray Yugoslavia exclusively in a negative light, as well as those that refer to it only in a positive way. So, unlike the introductory text, that was probably intended to explicitly explain the ideological point of the whole project, the praises of Yugoslavia in this text are carried out in a more “sober” way. In that fashion, they point out the “construction of infrastructure that provided the satisfaction of the needs of the widest social strata”; “intensive development of education”; “extraordinary progressive social principles, such as equal pay for the same work (for men and women), voting rights (for women), full equality in marriage, divorce by mutual agreement and the right to abortion”; “large state investments in the construction of hospitals, education of medical personnel, modernization of infrastructure of the health institutions and the implementation of the effective scientific achievements in the treatment and suppression of diseases”; “accelerated industrialization”; “development of the electric power network, the railroad, shipbuilding, machine building, steel factories, chemical factories,” which all entailed an “increased work productivity and modernization of the production process.” Then it is stated that “such a social progress resulted in a large rise in the living standard of the wide population strata, which was reflected in the quality of nutrition, clothing, and supply of homes with infrastructure that provided a comfortable living, such as heating, electricity, indoor plumbing, furniture and home appliances of better quality, and so on.”

The authors, in their evaluation of Yugoslav society, use the thesis of Canadian economist Michael Lebowitz, who deems that the “condition and categorical imperative of socialism” consists of: 1. social ownership of the means of production; 2. social production organized by the workers; 3. the satisfaction of common needs and intentions. The authors immediately state that in the “social reality of Yugoslavia it is impossible to locate the implementation of all of the three sides of the triangle, adding immediately that “this could be” the consequence of the fact that this was really a “system in the making, a system which was not finished up to the level at which we would speak about a reproduction of an organic regime of social production of a socialist type.” We could, rather, say that none of the sides of the triangle could be located, except formally.

Despite this, in order to characterize the Yugoslav system as “really existing socialism” it is necessary to invoke again the quasi-Hegelian rhetoric of “contradictions,” this time in the form of Lebowitz’s concept of “contradictory reproduction” which suggests that “during socialism, there were different logics in place, that functioned in a contradiction to each other.” These were the logic of capital (embodied in managers), the logic of the vanguard (embodied in the Party) and the logic of the working class. These logics were contradictory to each other, so according to Lebowitz, “exactly because there existed a contradictory reproduction between different sets of productive relations, the interaction of the system can generate crisis, inefficiency and irrationality that cannot be found in any system in its pure form.”

From this, a claim about a socialist character of the Yugoslav system is deduced, about the time when “socialist ideas came down to reality in an attempt to build a different world,” despite the survival of the harmful “logic of capital,” today we can find in an “open horizon of opportunities” a “renewed vision of a socialist future,” exactly “thanks to a precious experience of the socialist past.” Besides this, it is claimed in the text, enthusiastically and incorrectly, that: “The idea of the construction of new socio-economic system wasn’t imported from the Soviet area of influence, but was indigenously developed under the decisive contribution of the People’s Liberation Movement in the destruction of fascism.”[2]

2.

This vocabulary, in fact, represents a revival of the (post)Stalinist ideological vocabulary of the Yugoslav ruling class. The contradictions on which this class insisted were the contradictions of the “transitional period.”

So, we can see that the high-ranking SFRY functionary Mijalko Todorović – Plavi (People’s Hero and Hero of Socialist Labor[3]) advocated for a view according to which (as he stated in the 1965 book Liberation of Work) “the law of value is the general objective law of the transitional period.” He saw socialist self-management as a system which “automatically” provides better efficiency, productiveness of work, and living standards, which, according to him, is proven by the structure of personal consumption and indicators such as the number of individuals with high education, circulation of books, attendance of theatrical plays, and so on. The rise of the standard of living is reflected in the “diversity provided and imposed by the free initiative of direct manufacturers and by the direct willful influence of consumers and other beneficiaries and interested parties.” According to Todorović, the wish to abolish the law of value immediately “as soon as we took power” is romantic, idealistic, and even religious. On the contrary, this law needs to be conquered and used, until objective circumstances for its disappearance are built:

“As we will see later, our new socialist relations in the conditions of commodity production, contain this contradiction, that can give birth to, as a by-product, various negative phenomena, antagonisms, political, and other conflicts. Because of this, the identification and existence of the law of value and its use in progressive efforts entails a simultaneous identification of corresponding organic weaknesses, also born from the law of value and the new relations developed in the given conditions. The law of value is not new but has a typically socialist phenomena and quality (some almost brag about it as socialist attainment). But, it is reality – one which cannot by bypassed or denied. Furthermore, it can very efficiently be harnessed for the socialist cause, under the condition that all of its qualities are known, bad as well as good ones!”

Another high ranking member of the Yugoslav ruling class, Svetozar Vukmanović – Tempo (also People’s Hero and Hero of Socialist Labor), in 1966 spoke similarly about workers strikes and their demands:

“Even less justified is if some work collective demands higher pay regardless of the results of the business. Such demands are in their basis a demand for the state to, by taxation, take a part of the earnings of a more successful company and give it to another. And would therefore be a wage-leveling („uravnilovka“) with all the negative consequences on further economic development. Collectives would then be interested not to make efforts in work, but for the state to provide the pay for them.“

Writing about the same theme (“distribution according to the individual quantum of work”) in 1961, sociologist Dragomir Drašković pointed out that the Yugoslav system is such a social system “in which self-management and direct socialist democracy achieve increasingly perfect and humane forms,” but that in itself it contains a “contradictory process in which forms of alienation of consumers are expressed” …nevertheless, self-management represents a first step towards dealienation, which “doesn’t mean that social ownership of the means of production has abolished alienation, nor that the first appearance of self-management has liberated humanity from wage relations.” According to him, workers (“producers”) are now managing the surplus value, but in an indirect way: “Rewarding, that is, social distribution of income, according to the individual quantum of work, represents the abolishment of wage relations and opens the process of dealienation in the work place.” This process “resolves the dialectical contradiction of alienated work and represents the beginning of economic dealieanation which, in the system of worker’s self-management, increases opportunities for the affirmation of free work and a free man as producer.”

3.

Along with the (post)Stalinist ideological vocabulary of the ruling class, which remained in the tradition of “dialectical materialism,” in Yugoslavia there existed a suppressed and marginalized critique of the Yugoslav system that was sometimes based on libertarian socialist foundations.

Jelka Kljajić Imširović (1947-2006), who was active in the radical current of the ’68 student movement, wrote the following about her critical views from that period, not only regarding the Yugoslav system, but also regarding what she considered the insufficient criticisms of that system by the group Praxis[4]:

“In the case of the new type of class society, I was of the view that it is logical not to call it socialism at all. To call a society in which class relations are created and reproduced [socialist] meant rendering the very idea and struggle for socialism meaningless. Finally, I will mention only one more objection that I made that year, a long time ago, to the members of Praxis. It was about tying of Stalinism to the Soviet society. They did this, in my view, explicitly and implicitly, both the Praxis-ists who thought of Stalinism as a negation of socialism, and those who, along with a sharp critique of it, nevertheless classified it as a form of socialism. Without an analysis of the Stalinism of KPJ [Komunistička partija Jugoslavije – Communist Party of Yugoslavia], I thought, there is no concrete critical analysis of Yugoslav society.”[5]

Fredy Perlman (1934-1985) who in the sixties lived in Belgrade[6], and who after that experience radicalized his perspectives and separated from orthodox Marxist views, wrote at that time very clearly about Yugoslavia:

“The principle ‘to each according to his work’ was historically developed by the capitalist class in its struggle against the landed aristocracy, and in present day Yugoslavia this principle has the same meaning that it had for the bourgeoisie. Thus the enormous personal income (and bonuses) of a successful commercial entrepreneur in a Yugoslav import-export firm is justified with this slogan, since his financial success proves both his superior ability as well as the value of his contribution to society. In other words, distribution takes place in terms of the social evaluation of one’s labor, and in a commodity economy labor is evaluated on the market. The result is a system of distribution which can be summarized by the slogan ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his market success,’ a slogan which describes a system of social relations widely known as capitalist commodity production, and not as socialism (which was defined by Marx as the negation of capitalist commodity production).”[7]

In the book from 1991, Od staljinizma do samoupravnog nacionalizma (From Stalinism to Self-managed Nationalism), Jelka Kljajić Imširovć analyzed the development of the ideology of KPJ/SKJ. In the following way she summarized the pro-work essence of this ideology, as it was presented at the Fifth Congress of KPJ: “As the ruling one, the working class has to radically change – and according to the party’s evaluations it is most of time doing just that – its relation towards work and the state. Now it needs to lead in work, in the mobilization of all of the workers for the constructive efforts, for the increase of production, for the increase of labor productivity, for the development of the productive forces, for the, as correct as possible, implementation of the policy of the Party in economic and organizational questions. Work and only work, competition in work, work discipline, shock work [udarništvo[8]], struggle against non-work, unconscientious work, non-implementation of work assignments and quotas, cooperation with the management of companies, with constructive pointing out of mistakes in order to achieve even better and more efficient work, work enthusiasm in the implementation of economic plans adopted and developed by the Party and the State – these are the only ways and guarantees, along with the support for the Party and State in the struggle against the class enemy, for the ruling position of the working class (and working people) to become in the material and social sense better and better.” The ideology of work did not solely remain a means of increasing production, but also a manner by which to affirm loyalty to the Party and the leadership. Thus, the representatives of work collectives in this congress announced that the quotas and plans would be exceeded as a sign of solidarity with Tito and the Party, and in honor of the congress, work was organized into competitions.

Yugoslav sociologist with a libertarian-socialist orientation, Laslo Sekelj (1949-2001), stated in his 1990 book Jugoslavija – struktura raspadanja (Yugoslavia: the Process of Disintegration), that, although official Yugoslav ideology always invoked Marx, “the concept of socialism in the ideology of the Yugoslav and real-socialist parties was always reduced to the Leninist notion of socialism as delayed communism.” Such an understanding of socialism was, according to Sekelj, completely foreign to Marx who, although he rarely used the term, by socialism meant the lower phase of communism, in which the market is already abolished and there is no money, but in which there still remains the rule of reward according to work: “Individual share in the distribution depends on the number of work hours based on the principle of equal reward for different concrete work. The basic ideological principle of Yugoslav self-managed and every other real socialism is completely the opposite: different reward for the same quantum of work, depending on the kind of concrete work, that is, market results, which is the ideological principle of liberal capitalism.”

4.

Robert Kurz (1943-2012) thought that[9], in some way, the Mensheviks were right when they were pointing out that the revolution in Russia had an “objectively bourgeois character,” according to him in a logical, not in a historical or empirical, sense. The task of bourgeois modernization in Russia could not be fulfilled by the agent that fulfilled it in the West – the “liberal bourgeoisie” – which in the Russian revolution played only a secondary role. This could be done only by a worker’s party clearly differentiated from western capitalism, which was the only one capable of implementing a program of catching up with the capitalist development (“catch-up modernization”). The Bolsheviks were, in that sense, right about the “practice”: they had to implement a program of ideological deceit. So, communism became a “proletarian” ideology for the legitimization of a forced late bourgeois modernization.

Kurz stated that the presentation of this program of “socialist capital accumulation” – which has a completely capitalist character – can clearly be seen in the writings of Lenin and Stalin. Lenin glorified German state-capitalism as a model for development, and in doing so he defined state capitalism quite obtusely, very imprecisely differentiating it from “socialism.” Stalin clearly described the logic of accumulation in the system of commodity production, which produces abstract “profits” in the form of money, where this whole process is not considered capitalist because the “parasitic class” of old “capitalists” is expropriated. A statist regime of accumulation was named socialism, and such a regime was, more or less successfully, realized in other places too.

One of the variations of such a system was Yugoslavia. Historic aberrations from the Soviet model haven’t made the Yugoslav system any less capitalist than the original model was.

“To make things even clearer, let us first of all take the most concrete example of state capitalism. Everybody knows what this example is. It is Germany. Here we have “the last word” in modern large-scale capitalist engineering and planned organization, subordinated to Junker-bourgeois imperialism. Cross out the words in italics, and in place of the militarist, Junker, bourgeois, imperialist state put also a state, but of a different social type, of a different class content—a Soviet state, that is, a proletarian state, and you will have the sum total of the conditions necessary for socialism. Socialism is inconceivable without large-scale capitalist engineering based on the latest discoveries of modern science. It is inconceivable without planned state organization, which keeps tens of millions of people to the strictest observance of a unified standard in production and distribution.” (Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder)

“While the revolution in Germany is still slow in “coming forth”, our task is to study the state capitalism of the Germans, to spare no effort in copying it and not shrink from adopting dictatorial methods to hasten the copying of it. Our task is to hasten this copying even more than Peter hastened the copying of Western culture by barbarian Russia, and we must not hesitate to use barbarous methods in fighting barbarism.” (Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder)

“Clearly, construction work on so large a scale would necessitate the investment of thousands of millions of rubles. . . . But we were then a poor country. There lay one of the chief difficulties. Capitalist countries as a rule built up their heavy industries with funds obtained from abroad, whether by colonial plunder, or by exacting indemnities from vanquished nations, or else by foreign loans. The Soviet Union could not as a matter of principle resort to such infamous means of obtaining funds as the plunder of colonies or of vanquished nations. As for foreign loans, that avenue was closed to the U.S.S.R., as the capitalist countries refused to lend it anything. The funds had to be found inside the country.” (Stalin, The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks))

“And they were found. Financial sources were tapped in the U.S.S.R. such as could not be tapped in any capitalist country. The Soviet state had taken over all the mills, factories, and lands which the October Socialist Revolution had wrested from the capitalists and landlords, all the means of transportation, the banks, and home and foreign trade. The profits from the state-owned mills and factories, and from the means of transportation, trade and the banks now went to further the expansion of industry, and not into the pockets of a parasitic capitalist class. . . . All these sources of revenue were in the hands of the Soviet state. They could yield hundreds and thousands of millions of rubles for the creation of a heavy industry.” (Stalin, The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks))

5.

So, we saw that the rhetoric that emphasizes alleged contradictions of a “transitional period” or “socialism” is in reality the ideology of the ruling class of a state-capitalist system; that is, the rhetoric of a class war waged against the proletariat. Orthodox Marxism (that is, the mainstream of the historical left, represented by the line Second International – Third International and later derivatives) is one of the consciously most pro-capitalist ideologies that ever existed – that’s why it has such a clearly defined exploitative and pro-work character reflected in the warnings addressed to the Yugoslav proletariat, that pointed out the necessity to “change the relation towards work.”

This is completely in the spirit of Lenin’s warnings from 1918:

“The Russian is a bad worker compared with people in advanced countries. (…) The task that the Soviet government must set the people in all its scope is – learn to work. The Taylor system, the last word of capitalism in this respect, like all capitalist progress, is a combination of the refined brutality of bourgeois exploitation and a number of the greatest scientific achievements in the field.” (The Immediate Task of the Soviet Government)

In the class war waged in Yugoslavia, the ruling class articulated its interests through this rhetoric with the help of its basic instrument, state repression, while the proletariat attempted to resist it through different rebellions – workers strikes, peasant uprisings, student demonstrations – which appeared more or less throughout the whole period that Yugoslavia existed.

According to the available data, the first strikes in Yugoslavia appeared in 1958, among the miners of Trbovlje and Zagorje ob Savi in Slovenia. In Trbovlje all of the 4000 miners and other employees were on strike. The cause of the strike was low wages, and before the start of the strike the workers tried negotiating the work conditions with the authorities for almost a year. The miners were also demanding better work protection. Then, about 1200 miners from Zagorje ob Savi also started striking in solidarity with the miners of Trbovlje. The fact that some of the demands were that free clothing and footwear should be provided to all workers annually, as well as that overtime and Sunday work should be paid additionally, speaks a lot on the position of workers as the “ruling class.”

The workers of Trvoblje were known as organized and socialistically inclined workers since the period before Second World War, who didn’t shy from physical confrontations with their enemies.[10] In general, it was characteristic of these early strikes in Yugoslavia that the older workers saw strike as a tool of workers struggle more clearly and were the ones who were most ready to use it.

After the strike ended, the organs of the mine (formally the organs of workers self-management) and the organs of local authorities demanded that “adequate measures should be taken against the individuals that have a negative and suspicious past” and the existence of enemy activities during the strike was pointed out. The mine’s workers council adopted unanimously amongst its conclusions the following remark about the “irresponsible elements” that were active during the strike:

“We need to brand these people as the hostile elements to our socialist community and the interests of the working people. Because of this, the Workers council will, in the future, condemn all of the unjustified incidents of this kind and demand the organs of the authorities to deal with individuals like that according to our laws.”

Besides this, especially active was the Alliance of Women’s Societies of Zagorje (Savez ženskih društava Zagorja), which adopted a resolution condemning the insidious actions of a few rabble-rousers, and expressed regret that “even some women were duped by the instigators and that they behaved as if the miners are striking in the conditions of a capitalist regime.” The organization then reminded the miners that the working class “today has the power in its hands” and through its organs it can always express difficulties and justifiable demands: “Who acts differently is spitting on the heritage of the people’s liberation struggle, on the heritage of the working class and on our socialist development. Such a person is the enemy of the working people.”

Next year, in 1959, there were 150 strikes, and in 1964, there were 271 workers strikes. From that year until 1969, there were 869 strikes with 77.596 workers participating. The strikes were spreading more and more. At first, they appeared in the most developed areas of Yugoslavia and, in the end, in the poorest. The first strike in Kosovo was in 1968, 10 years after the strike in Trbovlje. Strikes mostly lasted for a short time, the authorities attempted to end them as quickly as possible by granting some of the demands. The media in most cases didn’t report on the strikes, and if they did, they would report about them only after they were already finished and that situation was back to “normal.” The workers’ unions and the organs of workers self-management were completely passive during the strikes, so the workers were sometimes in conflicts with them as well. The workers were hiding who was in the “striking committees,” that is, who were the organizers of strikes. In most cases the damage caused by the strike had to be compensated through additional work of the workers. In 80% of the cases, it was the workers in production who were striking.

The number of strikes was on the continuous rise, so in 1980, there were 235 strikes with 13.504 participants, in 1983, 336 strikes with 21.776 participants, in 1986, 851 strikes with 88.860 participants, and in 1987, 1685 strikes with 288.686 participants.

In the eighties, ideas of connecting workers on the level of Yugoslavia appeared – that is, of overcoming the practice of organizing isolated strikes, and even ideas about starting workers’ unions that would be separated from the state. One of the workers active in this field was Radomir Radović (1952-1984). He was a union activist, close to the dissident socialist circles in Belgrade, and was pointing out the need for union organizing separated from state structures. Radović was fired because of his activities against one manager, and was under constant police pressure. During 1984, he was arrested repeatedly, and then was found dead under suspicious circumstances. The official version of the authorities was that he committed suicide, but his friends thought that he was murdered. His friend Jelka Kljajić Imširović thought that Radović was a victim of a police and political crackdown of their dissident circle, “specifically because he was a worker, and with that, educated and politically active within the union.”

While the question of workers’ strikes was problematic for the ruling class of Yugoslavia above all because of the ideological and propaganda thesis about proletarians as the real ruling class, for the peasants there was already a prepared ideological matrix in place, the one about the “hostile kulak elements.” This matrix was often applied to poor peasants as well, that were often partisans, and sometimes it reached ridiculous proportions, like when, in 1945, Aleksandar Ranković accused kulaks that they trying to compromise new authorities, among other things, by “committing suicides by jumping through windows.”

Pressure was directed towards the peasantry particularly in the 1946-1953 period, which also includes the period directly after the break with the Soviet union. This pressure was, in the first place, reflected in the obligatory buyout of agricultural products as well as in the collectivization which was implemented and modeled on the one in the Soviet Union. Sometimes the obligatory amount of a specific agricultural product that the peasants had to sell to the state was greater than the average produced amount of that product in that year. This kind of pressure led to several attempts of organized peasant resistance.

On May 6th 1950, after preparations, an attempt of an armed insurrection of peasants started in the region of Cazinska Krajina in Bosnia, and in Kordun in Croatia, two areas that border each other. A big majority of rebels in the Bosnian part of the insurrection consisted of Bosniaks, but they chose as their commander an ethic Serb. This was a partisan fighter from ’41, Milan Božić. At the same time the leader of the Kordun part of the insurrection was Mile Devrnja, also a partisan fighter from ’41.

That year the peasants were struck by a catastrophic drought, so they were not able to fulfill the imposed, and already unrealistic, obligations towards the state. They were subjected to brutal pressure, which included police harassment, confiscation of property and mobilization for enforced labor (logging, construction and factory work). Starting an armed insurrection was therefore a move of the desperate that were unable to rebuild their homes, which were destroyed during the war, and feed their families.

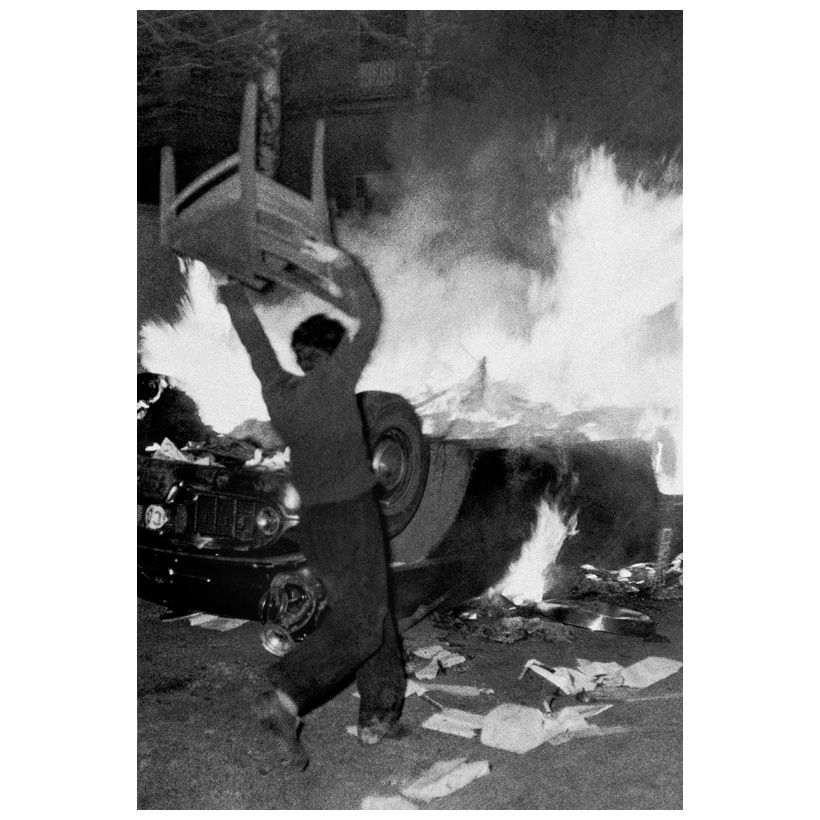

After the insurrection broke out, the peasants burned down several archives of the local authorities (similar to the way the partisan insurrection started in ’41), disarmed several cops (the police commander was later shot by the authorities, because he didn’t put out an armed resistance to the rebels, despite being confronted by a force one hundred times stronger than his own), took down telegraphic pylons, confiscated several cooperative storage rooms and captured several political functionaries.

This poorly organized and ideologically confused insurrection of the desperate was quickly and easily suppressed by the state, when it sent several hundred soldiers against it. In the action of capturing of the rebels, about 15 of them were killed, and more than 700 were arrested. Eighteen were condemned to death, and six of them were shot (Milan Božić, Ale Čović, Hasimbeg Beganović, Stojan Starčević, Mile Devrnja, Nikola Beuković), while the rest had their sentences converted into long prison terms. Two hundred and seventy-five people were sentenced to long prison terms including life sentences, only a small number got sentences below 10 years. As a consequence of the hard labor in the Zenica mine, several of the convicts died and some of them committed suicide.

Following this, the families of the Bosniak rebels were forcefully displaced to Srbac.[11] That is how approximately 70 to 100 families were moved, who were forbidden to carry belongings with them, and were moved in cattle train cars: “Train cars were locked, there was not enough water even for the children, and all [bodily] needs were done in the train cars. The stench was everywhere. No one asked us if the children had anything to drink or eat.” (testimony of Bejza Čalić). In Srbac, the elderly exiles were engaged in begging, and the children cared for the cattle of the richer locals.

According to Svetozar Vukmanović, another high ranking official Jovan Veselinov (is there even a need to mention: Peoples Hero and Hero of Socialist Labor), said the following about the conflicts with the peasants from this period: “Thousands of peasants were arrested and convicted. Some are also dead. People defend the little wheat they have with axes. There are some kulaks, but the majority is our people! In the people’s liberation struggle they were on our side, now they’ve become the enemy. Not because they are kulaks, but because the buyout was set too high. Our activists that are pushing the buyout have separated themselves from the people. They are the same people who were the most popular during the war, and have now become the most hated.”

The rebellions of students and the youth against the new authorities started very early on. Already in the end of the ‘40s there were sporadic arrests of young people, even pupils, because of political activities against the authorities. One such group was, for example, a group of schoolgirls from Belgrade (Nađa Poderegin, Leposava Milošević, Milana Ilić) who distributed flyers accusing the authorities of betraying the goals of communism, and that those authorities were beginning to get rich.

Two students of the Civil Engineering Faculty in Belgrade spoke in 1952, at a student gathering, against the new economic measures that were making the position of poor students even worse. The next year, those same students were in court, and the trial transformed into a student demonstration which included a physical confrontation with the police.

The first bigger student demonstrations happened on the 29th October 1954, in Studentski grad[12] in Belgrade. The reasons were connected to the low standard of living for students, especially in regards to accommodation and food. During the whole year the atmosphere in Studentski grad was charged, with frequent conflicts with the police. When the demonstration started, around a thousand students headed from Studentski grad towards the center in Belgrade. They were stopped by the police, which applied brutal force and arrested many students. The students shouted slogans against the government and threw stones at the cops.

For the same reasons, student demonstrations started in Zagreb and Skopje in 1959. In the demonstrations in Zagreb between 1000 and 3000 students were in the streets. When the protests started in Skopje, the local students connected them with the ones in Zagreb. The Zagreb demonstrations were quickly stopped, after the arrest of a smaller number of students. In the same year there was a student strike in Rijeka.

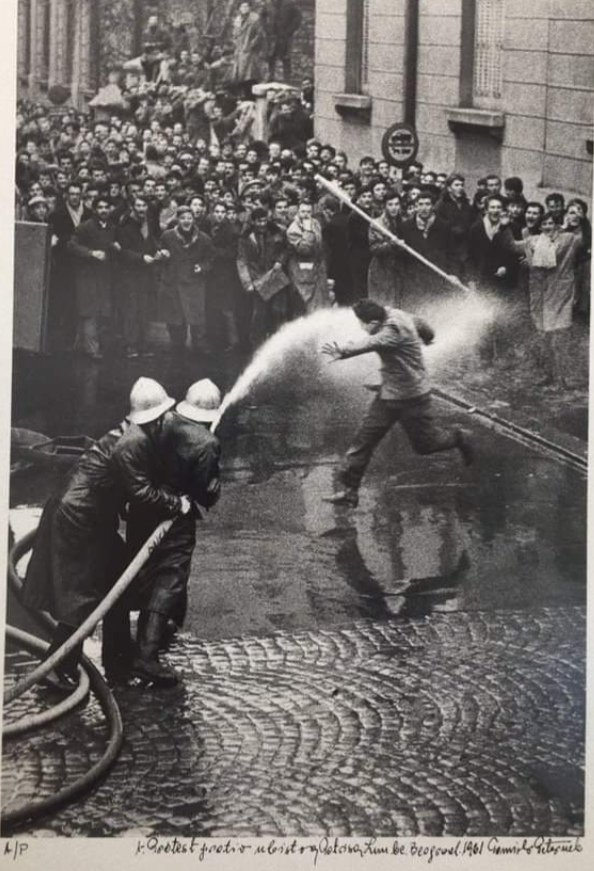

In the sixties, a few demonstrations were at first organized with the support of the authorities, but then transformed into confrontations with the police. In 1961, in Belgrade, demonstrations were held because of the murder of Patrice Lumumba, and then they became a clash with the cops, in which there was also an attack on the Belgian embassy. In 1966, in Belgrade, Zagreb, and Sarajevo there were demonstrations “in the support of the people of Vietnam.” In Belgrade, around 3000 people participated, and this protest too transformed into a clash with cops. The police used tear gas, water cannons and batons against the demonstrators, and a number of them were arrested.

The best known example of a student rebellion in this period, which was at the same time the most massive, organized and politically articulated, was the one from 1968. In Yugoslavia in that year student demonstrations were organized in Belgrade, Zagreb, Priština[13], and other cities. In Belgrade, again student riots started in Studentski grad, in the beginning because of the low student standard of living, and then they developed into demonstrations against the new class society and the “red bourgeoisie.” Already on the first day of demonstrations, on the 2nd of June, a fierce conflict with the cops broke out in which firearms were used. The student rebellion lasted for seven days, during which students occupied the Faculty of Philosophy, and proclaimed the establishment of the “Red University Karl Marx,” regularly held assemblies (which they called “convents,” after the French Revolution), published their newspaper, and gained the sympathies of public personalities and society in general. This movement also contained a more radical wing, which negated the socialist character of the Yugoslav society and tried to develop a radical critique of it. With a skillful maneuver of Tito himself, this protest was “supported,” along with isolating “counter-revolutionary elements,” meaning the radical wing of the movement. Members of this circle continued to be submitted to state repression in the following years. One example of that was the trial of Jelka Kljajić, Pavluška Imširović and Milan Nikolić from 1972, after which they were sentenced to prison terms.

A characteristic representation of the radical content of the student demonstrations from 1968 in Belgrade is contained in the text “Down with the red bourgeoisie of Yugoslavia,” by anonymous authors[14], which is a report on the events in Belgrade, published in the same year in the anarchist magazine Black&Red from Detroit:

“Call what you have created what you like, but don’t call it socialism. We here are for real power in the hands of the working class, and if that is the meaning of self-management, then we are for self-management. But if self-management is nothing but a facade for the construction of the competitive profit mechanism of a bureaucratic managerial – why don’t I say capitalist – class, then we are against it. No, you are not socialist and you are not creating socialism.”

6.

The priests promise to those who suffer, eternal bliss after death, but suffering today; socialists promise prosperity somewhere in the far future, and patience today. So, will we, as well, dumb down people with one more faith in the future society? If we know that faith is a need of only those who suffer, so that they wouldn’t rebel, and to more easily bear their unbearable life of slavery. If there wasn’t faith, which still today keeps people in slavery, they would rebel, free themselves of their false beliefs and the chains that burden them.

Newspaper Anarhija, Belgrade, 1911.

I have based my affair on nothing.

Max Stirner

In the Belgrade newspaper Politika, surrealist (and communist) Marko Ristić[15] published a text in 1971 where he explained his persuasion for Yugoslavia, or as he put it himself, FOR THIS YUGOSLAVIA: “If we were not living right in this moment, on this Planet, as it is today, in this world that is divided into blocs, this violent, militarized, racist, nationalist, neofacist world in which there is no survival for us, the peoples of Yugoslavia, outside Yugoslavia, outside yugoslavism – and no republican statehood can, nor will it, save us – I would perhaps, consistent with internationalism, declare myself a “citizen of the world,” that is, of Utopia. But, as this is not the case, Yugoslavia seems to me to be our only hope, and that it will be this for a long time, simultaneously a minimal and maximal, unavoidable and unavoidably relative reality.”

This was a smooth-spoken, abandonment of the Impossible[16]. The abandonment which is today sometimes romanticized and glorified as kind of an almost-cosmopolitan principle, even though it represents its negation.

More than 50 years earlier, another Yugoslav communist expressed a completely opposite feeling towards Yugoslavism. This was Rudolf Hercigonja[17], who only a few years before this statement considered himself to be a Yugoslav national-revolutionary, and committed to the cause of the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian empire and the creation of a Yugoslav state. When he was, with the creation of Yugoslavia, freed after a four year imprisonment, he realized that the warden of Lepoglava, the prison where he was held, stayed the same, that the system of state repression stayed the same, and it was now carried out only under the robe of the so-called free state of the south Slavs. In a pamphlet from 1919[18], Hercigonja concluded his indignation and rejection of a system such as that with the statement that those who were “tortured, murdered and abused for the sake of that Yugoslavia (…) are today again hunted animals, without any rights or protection (…) Which means that the whole Yugoslavia is one large Lepoglava (…) And all of our reaction is one horrific old cellar in which they suffocate, torture and murder innocent people (…) Oh, give us dynamite, lots of dynamite, to fill up all of the terrible hollow places of the old cellar, and to blow up whole of Lepoglava into nothing.”

In this period, Hercigonja became one of the founders of the communist movement in Yugoslavia, and participated in the faction of this movement that was opposed to parliamentarianism, and was, for this reason and others, called an anarchist faction[19]. Because of his commitment to the militant methods of struggle, he had to emigrate, and in the end he settled in the Soviet Union. This man, who disowned Yugoslavism, in the beginning because of the real meaning that state repression of revolutionaries and poor people had to him, embodied in the prison system, ended his life in a Soviet dungeon, where he was murdered in 1938.[20]

***

Authors of the exhibition and publication “We raised cities for you – On the contradictions of Yugoslav socialism,” took this title from the revolutionary song Padaj silo i nepravdo (Fall, oh, force and injustice), written in the 1920s and dedicated to the Hvar rebellion[21].

However, although they took a verse from this song for the title for their project, they failed to provide, at least, the whole stanza where that verse is contained:

We raised cities for you,

Built keeps and towers.

We have always been slaves,

and we labored for you.

Continuous reference to the supposed contradictions of the Yugoslav system directly continues the ideology of the Yugoslav “red bourgeoisie,” who similarly pointed out the contradictions of the so-called “transitional period” and completely ignored the perspectives of the radical critics of that system who, in it, clearly saw a capitalist character.

This mystification had a clear goal: to justify the class war waged against the proletariat which was managed by the “red bourgeoisie.” Therefore, it is logical that, today, those who rely on this ideology and this mystifying view of Yugoslavia, are those who want to be managers of our enslavement and misery, and who have the ambition to enclose us in the eternal limbo of the transition from capitalism to capitalism through capitalism, calling this, at the same time, the road towards our final liberation, which will of course never come. This is a perspective that always and again expects new sacrifices and toiling, and in return it promises sometimes little-better conditions of enslavement (depending on how much this is allowed by the market – the only true capitalist manager) and the glorification of our work and sacrifices.

Nationalist and capitalist states which became independent after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and about which the leftist complain – as well the “logic of capital” which dominates them – have all been established and, as states, defined in the context of the Yugoslav federation (with the category of “constitutive nations” included). Meanwhile, the logic of capital – that is, the logic of “socialist accumulation of capital” – was in the core of that system which contributed to the development of the contemporary capitalist society more than any previous regime in this region.

All the variations of the Yugoslav idea were in their character, above all else, statist – and further carried with them all of the power relations, tensions, expectations and conformisms that follow every hierarchical and authoritarian organization of the human sphere. Statist frameworks always carry self-devastating and degrading relations between people, as well as brutal repression, which is a necessary condition of capitalist development. The examples of the repression led by the Yugoslav state in this text are only hinted at, and a framework is offered for the understanding that repression as a necessary condition for the development of modern productivist mass society, that is, for the “socialist accumulation of capital“.

Yugoslavia is a spook whose purpose of existence is the justification and further continuation of a system based on our misery. All of the Yugoslav ideas, in all of their variants, be they of national-romantic or of “real-socialist” character, have that same, mystifying, reason for existence.

Against Yugonostalgia and Yugofuturism, against every Yugoslavia.

For life and anarchy.

Used and useful books (in addition to the all already mentioned texts):

Branislav Dimitrijević, Potrošeni socijalizam [Consummated Socialism], Fabrika knjiga, 2016.

Milinko Đorđević, Sedam levih godina [Seven left years], Naš Dom, 2000.

Jelka Imširović, Od staljininizma do samoupravnog nacionalizma [From Stalinism to self-managed nationalism], Centar za filozofiju i društvenu teoriju, 1991.

Neca Jovanov, Radnički štrajkovi u SFRJ 1958-1969 [Workers’ strikes in SFRY 1958-1969], ZAPIS, 1979.

Neca Jovanov, Dijagnoza samoupravljanja 1974-1981 [Diagnosis of self-management 1974-1981], SNL, 1983.

Neca Jovanov, Sukobi [Conflicts], Univerzitetska riječ, 1989.

Vesna Kržišnik-Bukić, Cazinska buna 1950 [Cazin Rebellion 1950], Svjetlost, 1991.

Miodrag Milić, Rađanje Titove despotije [The birth of Tito’s despotism], Naša reč, 1985.

Laslo Sekelj, Jugoslavija: Struktura raspadanja [Yugoslavia: Structure of disintegration], Rad, 1990.

Živojin Pavlović, Ispljuvak pun krvi [Spittle Full of Blood], Dereta, 1991.

Nebojša Popov, Društveni sukobi – Izazov sociologiji [Social conflicts – Challenge to sociology], Službeni glasnik, 2008.

Nebojša Popov, Contra Fatum, Mladost, 1988.

[1] We are left to wonder where was this “real independence” between the period of Stalinist loyalty and the period of Yugoslavia as a de facto member of NATO.

[2] The Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) went through a period of intensive bolshevization and Stalinization, which also included the physical destruction of the leadership and membership of the party, in which the leadership from the WW2 period also participated. In this process, hundreds of communists and other Yugoslav revolutionaries were killed. The period of NOB (People’s Liberation Struggle) was also not free of these kinds of activities, for example during the existence of the “Užice Republic” Živojin Pavlović, a functionary of KPJ, who became a fierce critic of Stalinism, was tortured and killed.

[3] Honorary titles in Yugoslavia.

[4] For a newer critique of Praxis, from a left-communist perspectives see Juraj Katalenac: Praxis: an attempt at ruthless criticism, www.ritual-mag.com

[5] Excerpt from the text Dissidents and Prison by Jelka Kljajić Imširović, which is included in this issue of Antipolitika.

[6] Concerning this, see the article by Lorrain Perlman: Three Years in Yugoslavia, included in this issue of Antipolitika

[7] An excerpt from the text by Fredy Perlman: The Birth of a Revolutionary Movement in Yugoslavia, also included in this issue of Antipolitika.

[8] An udarnik, also known in English as a shock worker or strike worker (collectively known as shock brigades or a shock labour team) was a highly productive worker in the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, Yugoslavia. The term derived from the expression “udarny trud” for “superproductive, enthusiastic labour”.

[9] Robert Kurz: The German war economy and state socialism, libcom.org

[10] The clash of the workers of Trbovlje with the members of fascist Orjuna in 1924, in which there were dead and wounded, is well known.

[11] A town and municipality in Bosnia with an overwhelming Serbian majority.

[12] Large student dormitory in Belgrade (Novi Beograd) consisting of several blocks. It accommodates more than 4.000 students.

[13] Only in Priština was the army used against the demonstrators – which speaks about the position of Kosovo within Yugoslavia. The army was again used in 1981 against the demonstrators in Priština – this time the Army shot at them.

[14] The authors signed themselves only as “Black&Red correspondents,” the text is included in this issue of Antipolitika.

[15] Marko Ristić (1902-1984), one of the founders of the Belgrade surrealist group. Early on, he began correspondence with Andre Breton, and published surrealist translations (in the 1920s). The Belgrade group was formed in 1929 and, in the following years, some of the prominent members of the group joined the Communist Party. After WW2, Ristić was the Yugoslav ambassador in Paris.

[16] Nemoguće/ L’impossible – the title of the Belgrade surrealist magazine published in 1930.

[17] Rudolf Hercigonja (1896-1938) belonged to circle of the Yugoslav nationalist revolutionary youth of Zagreb in the period before WW1. He assassinated the Ban of Croatia in 1914, after which he was imprisoned. After the war he became one of the founders of KPJ and SKOJ (the communist youth organization). He belonged to the radical wing of the communist movement, and was one of the founders of the group Crvena pravda which in 1921 assassinated Milorad Drašković, the Minister of Interior of Yugoslavia.

[18] Rudolf Hercigonja, Lepoglavski vampiri, Zagreb, 1919.

[19] The circle that Hercigonja belonged to was in contact with the radical magazine Die Aktion from Germany. This group from Zagreb was for a time active outside of the party, under the name Communist Youth.

[20] The torture of Yugoslav and other communists in the Soviet Union, by the Stalinist regime, included not only the physical destruction of people, but also moral – one in which they were forced to prove their loyalty by ratting out on their friends. Hercigonja asked for permission in 1936 to leave for Spain as a volunteer, which was not allowed to him.

[21] The rebellion on the island of Hvar in the 16th century, which then grew into a civil war (1510-1514). The rebels were in conflict with the aristocracy and Venetian authorities.