IMAGE 1

Bonaparte visitant les pestiférés de Jaffa (Bonaparte visits the plague stricken in Jaffa, oil on canvas, 1804, Louvre, by Antoine-Jean Gros) is a propaganda painting idealizing Napoleon’s disastrous Egyptian campaign. It shows his (alleged?) visit to his sick soldiers in March 1799 in his attempt to reverse the negative rumors about him ordering plague victims to be “mercy-killed” by poisoning. The outbreak of the bubonic plague had followed the violent “sack of Jaffa” by the French army. This romantic oil-painting, with several neoclassicist elements, was exhibited in the months between Napoleon’s proclamation as emperor and his coronation. It portrays the emperor as god-sent healer offering the traditional “royal touch”, as he thaumaturgically lays his hand on the armpit of one of the sick.

Clandestina, November 2015

1. war as spectacle within the bourgeois subject

The battlefield had become a mass spectacle decades before the discovery of photography. With the Napoleonic wars, the boundary between exercising lethal violence and observing it became blurred. Napoleon realized that in war, succeeding in propaganda is more important than winning a real military confrontation. Napoleon’s operations had to be celebrated as victorious, even if if they could not be won on a technical military level. They had to be described in detail and these glorious narratives of fighting battles had to be distributed as widely as possible. He was the first leader to make “live war reporting” as definitive as it still is for the subject formation of the Western citizen “in the peaceful world”.

Military operations in war had long become mass industrial affairs and could no longer be represented in their entirety by simple observers, such as painters or writers. Now that armies had technologies of mass destruction to their disposal, a whole variety of accounts, comments and descriptions, as well as knowledge of the stages of tactical and practical preparations were necessary for “a whole battle” to be recomposed in the Press for the news-hungry public.

Over the course of the 19th century, war itself started adapting to the requirements of the remote-controlled imagination of its consumers. Everyone could now have an opinion about how an operation would be best carried out, how its tactics should be interpreted, how a battle should be evaluated or repeated avoiding past failures. Soon, war had found a comfortable place in the everyday life of consumers in bourgeois States.

As a natural law of the global balance of power, real war would soon appear even banal.

This sense of a split between “peace at home” and “war abroad” (or “war elsewhere”) is expressed in most binary oppositions of meaning in the spectacular industries of the 20th century. The opposite genres of “news” and “entertainment” are emblematic of this dialectics – their merging in today’s “infotainment” carries their complementarity to its logical conclusion.

2. “the real thing”

Since the Napoleonic times, War and the Spectacle have been growing hand in hand. Together they are sowing the seeds of contemporary life.

At the end of the 19th century the cinema was still a second-rate attraction, next to the headless body, the bearded lady and the traveling circus. Its status changed with the Spanish-American war in Cuba. Vitagraph presented what it called “a document from the battlefield”. It was actually a short film shot in the studio, called Tearing Down the Spanish Flag (1898), where the US forces occupy a government building in Havana, pull down the Spanish flag and proudly raise the stars and stripes.

The success was followed by more such “documentaries”, with whole naval battles being set in bath tubs. The number of viewers increased dramatically, and so did the demand for more “war documentaries”. When the revolution and the war in Mexico broke out in 1910, several US companies approached both warring parties asking them for “exclusive footage”. In the urban myth that circulated in the US conceding Pancho Villa’s contract with Griffith’s Mutual Company, Villa carried out his battles according to the film director’s guidelines. There are no sources that confirm that his contract was any different from that of his opponent General Victoriano Huerta, but turning the revolutionary Villa into a caricature was essential for American capitalism: “We’ll make you a star, but only in a way that serves our interests”.

In any case, soon viewers found the scenes filmed live on the battlefield too boring. The film industry asked itself a simple question:Why record reality when we can actually construct it? Viewers would still have to believe they are watching “the real thing”. And indeed, these half-fictional, manufactured newsreels from Mexico became the most popular films of the time.

IMAGE 2

L. M. Burrud, a cameraman present in several of Villa’s military campaigns, poses for a publicity shot showing him “filming in action”. His two Mexican “bodyguards” are shown half-naked to conform to the American stereotype of the “Indian”.

3. reconstructing the past, building the future

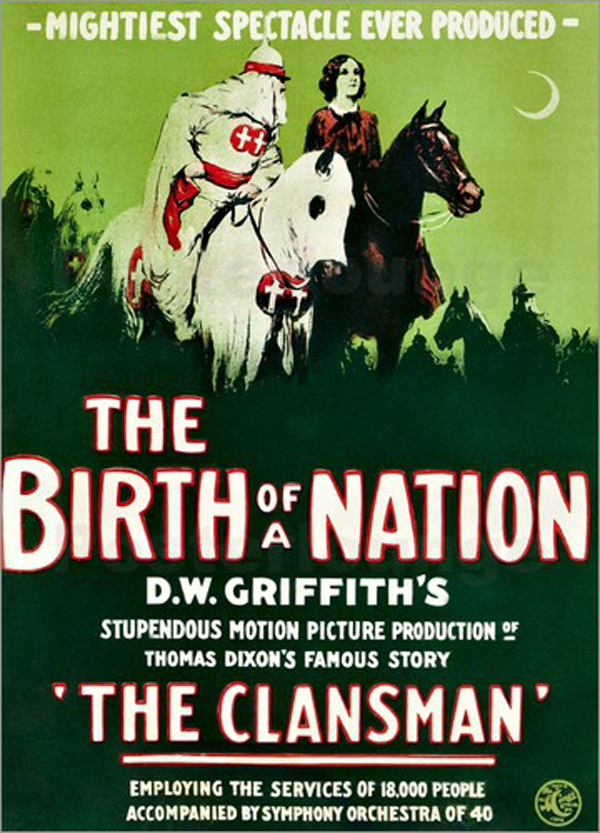

In 1915 the film director D.W. Griffith carried this idea that fiction can “help create reality” a step further. He actually managed to fictively “document” the past in a way that would directly influence the future.

His Birth of a Nation tells the story of the first Ku Klux Klan through panoramic battle scenes of the American Civil War. The film was produced and shown at a time of brutal class war – against blacks, immigrants, workers, proletarian women and children. There were widespread protests and riots by African-Americans against the screenings of The Birth of a Nation, in Boston, Philadelphia and other major cities, while thousands of white Bostonians flocked to see the film.

Birth of a Nation not only justified the mass-murderous activity of the first Ku Klux Klan (1865-1874) but also consciously contributed to the founding of the second Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. The impressive images of burning crosses and armies of knights in pointed hoods had never existed in the past, but were made up as an effective tool for racism at home and wars for expansion abroad.

In this case then, the film narrative did not merely disguise fiction as “objective historical documentation”, but helped turn an imagined future into actual reality.

Griffith’s great talent as a propagandist was appreciated by the British War Office and the French Government, when the US had to persuade its population to show some enthusiasm for entering World War I. His Hearts of the World (1918), filmed in Europe and Los Angeles and edited together with footage from stock newsreels, replaced the by now tedious static shots of dead bodies in muddy trenches of war films, with hysterical brutality (of the enemy), military heroism (of the allies) and breathtaking action.

IMAGE 3

“Birth of a Nation: The Mightiest Spectacle Ever Produced”: Sometimes commercial messages simply state the truth.

4. distance as a facilitator of murder

In his book Men Against Fire, published in 1947, the highly decorated US general S.L.A. Marshall, claims more or less that in human history, the greatest part of soldiers in combat did not attempt to kill, even if it was to save their own lives. He reached this conclusion based on his own research on infantry combat effectiveness in World War II and on written sources from the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil war. He stated that in World War II, under a quarter of US troops actually fired at the enemy for the purpose of killing, even when they were under direct threat. “The 25 per cent estimate,” we read in his sixth chapter, “stands even for well-trained and campaign-seasoned troops (…) These men [75% of troops] may face danger but they will not fight.”

Although Marshall’s “ratio of fire” theory has been fiercely criticized by other military historians for being offensive to infantry companies in World War II, his services as an operations analyst continued to be used by the US Army throughout his life, so that the death ratio be improved…

Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman, in his 1996 On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, uses findings from the Korean War in 1950-51, where now 45% of soldiers in combat were willing to shoot to kill, and from the Vietnam War, by which time the number had dropped to 5%: This does not mean, according to Grossman, that 95% of soldiers in combat who did shoot in the Vietnam war were targeting someone specific, since 52,000 shots were fired for each hit, which indicates that most of the shooting was mere “posturing”.

In fact, the magic factor that increased the murderous effectiveness of military operations was distance. Rates of death in combat from attacks by artillery and aircraft are immensely higher than amongst foot troops with a rifle. Distance reduces the reality of death by turning it into charts, graphs and symbols.

The sentimental distance will allow an armed individual to kill more easily from a short distance. The enemy is de-humanized in the eyes of the soldier (by military training and propaganda, with the help of drug consumption), and thus the enemy is treated either as a mere object, or as an inferior form of life (and our culture definitely teaches us that extinguishing inferior life forms is perfectly legitimate). In the Desert Storm Operation, “night vision” made fighting war feel like playing a Nintendo game.

With drone technology this distance from weapon to target of modern warfare has now been multiplied, including also the distance from the operator of the weapon to the weapon itself: A drone can be several thousand miles away from the person controlling it. The operator of the drone is not situated on some “battlefield”, there is no reciprocity in the direct threat to the enemy, or in the violence the operator inflicts.

Considering that the US Army alone owns over 6,000 drones of various kinds, and that the number is growing as we speak, they form an important part of military operations worldwide and are emblematic of warfare today. Until now, hunter-killer drones have been used in Afghanistan, but also in Somalia, Yemen and Pakistan. Drone warfare is legitimized by the US army and its theoreticians as “humanitarian”, and as “warfare without risk”. That probably means “without risk for the side of the drone operators”. The question that arises for the Western middle classes in peaceful regions is, in Gregoire Chamayou’s words (from his Drone Theory): “What would be the consequences of becoming the subjects of a drone state be for the state’s own population?”

In a world of constant warfare, the parties who are actually fighting each other are not distinguishable anymore. “Enemies”, “conflict zones”, “potential threats” and therefore “targets” are being invented anew all the time. So the “applied” answer to this question does not lie in some distant future.

IMAGE 4

In the era of drones, haute couture is finally more about aesthetics than about practicality.

5. war games and screen battles

From the cockpit of an F-16 flying at 5,000 meters, you can’t see, nor smell, nor be sprayed with the blood of “collateral damage.” The sensory reality of war has been detached, cleaned away from the “productive” activity of the warrior, as it has from the language of NATO’s reports on the alleged “mistakes.”

Massimo De Angelis and Silvia Federici

“The War in Yugoslavia. On whom the Bombs are Falling?”

http://www.midnightnotes.org/pamphlet_yugo.html

Virtual military training games like “Full Spectrum Warrior”, designed by teams of university scholars, game industry programmers and military advisors, turn war into a frivolous triviality. Their function is to construct a new psychosocial condition where constant readiness for war becomes an accepted part of a sane individual’s everyday behavior.

The technique is simple. The actual content of whole war universes in MMO (Massively Multiplayer Online) games connects the triviality of the war-form to the “natural expansiveness” of capitalism and the values of aggression for survival and racial inequality. Militarization and murderous expansion, miniaturized and turned into a harmless, immersive action-packed quotidian experience become commodified entertainment – entertainment that guides kids through the process of learning to treat life (potentially, in a bad psycho-social moment, also their own life…) as unworthy of anything but scorn and disdain.

The boundary between reality and representation in war, as well as between pedagogical murder-promoting images and descriptive-informative images of murder, has become blurred. Its very existence is challenged, (this time not just in ex-postmodern theory). The case of the Russian soldier who uploaded selfies on instagram from an unknown spot in the military confrontation for the control of Eastern Ukraine in July 2014, thus betraying his own location, might be slightly ridiculous. Yet the case of the ISIL volunteer uploaded on his twitter account a photo of his 7-year-old son holding the head of an ISIL victim, certainly is not.

IMAGE 5

So much livelier than the “real thing”

6. private troops, private weapons

According to Peter Singer’s Corporate Warriors: The Rise of Privatized Military Industry (2003) in the 1990s, the services of private contractors (PMFs=private military firms) were used in over 50 countries, in every single continent but Antarctica and there used to be 50 military personnel for every one contractor. In 2004 the ratio was 10 to 1. The number of contractors reached its apogee in Iraq, where in 2006 it is estimated that at least 100,000 of them were working directly for the United States Department of Defense.

Some UN officials point to the “difficulty separating private from public troops”, which means that legal proceedings against non-state contractors like PMFs do not necessarily burden the state that hires them for security and combat. There is currently no legal framework applied to these firms. A beneficial side-effect of PMFs for Americans has been the relative decompression of organized crime at home, since a lot of murderous activity is now being “exported”. Also, important killing know-how gained by Iraqi occupation forces is brought back home to be shared with the US police.

The war industry is one of the most powerful and dynamic sectors of the global economy. According to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) reports, in the last five years, the years of the so-called “global crisis”, the global arms trade has risen by 16%, with the US remaining the greatest export power: Their 31% share of the market accounts for a 23% increase between 2010 and 2014, compared to the preceding 5-year period. Russia, owning a 27% of global arms exports, presented an increase in their share by 37%. It has been estimated that every year, world military expenditure totals over 1.5 trillion dollars. The greatest part of this business corresponds to the sale of small weapons to “developing” countries.

According to a Reuters report, in 2007 there were 90 guns per 100 people in the US. On October 5, 2015, the Washington Post reported that “[t]here are now more guns than people in the United States”.

At the moment, there is roughly one firearm for every seven people on the planet.

IMAGE 6

The arms trade guarantees global harmony.

7. money is the homeland of war

The Enlightenment myth that the modern commodity-producing system sprang forth from a “Civilizing Process” (Norbert Elias) as the product of peaceful trade and development, bourgeois industry, scientific curiosity, inventions that raised the standard of living, and daring discoveries in opposition to the brutal culture of the so-called Middle Ages has proven tenacious. As the bearer of all these beautiful things is named the modern “autonomous subject,” which supposedly freed itself from feudal-agrarian bonds in favor of the “freedom of the individual.” What a shame then that the form of production that arose from this mass of pure virtues and progress is characterized by mass poverty, global pauperization, world wars, crises and destruction.

Robert Kurz, The “Big Bang” of Modernity

Was modern war born from the conditions imposed by the capitalist market, or did the use of cannons, innovative firearms and early modern private armies actually intensify abstract market relations and impose the expansion of capitalism? The question is hard to answer. In any case, if war and market today are not one and the same thing, PMFs and the global arms trade are only two of the links between them.

The people who make our clothes, our toys, packaging, building material, who send our post and repair our computers, work in factories built and organized according to the military model. Classic slavery conditions in Africa, China, SE Asia, Latin America, as well as automated workplaces like amazon.com all borrow insights and formal principles from the army. This seems like a metaphorical relationship between the management of big companies and principles of military organization, yet it extends far beyond metaphor.

From the first English and later French and Dutch colonial companies in the 16th century, which were licensed by King and State at home to have their own armies abroad, the expansion of markets for “development and enterprise” has always been connected to military operations and colonial plunder.

Also in terms of the “content” of production, the basic pillar of the “heavy” component of the chemical industries in Western Europe and the US in the 19th century was the modernization of war. Innovations in deadly gas, weaponry and ammunition, also contributed to the advancement of mass agribusiness and energy production technology, which in turn it managed to set global prices and control a big part of production, quality and distribution for fuel and basic foodstuffs and also to create tens of thousands of commodities for mass consumption.

Big companies manufacturing perfumes, soaps and medicine have always offered their innovations for weapons of mass destruction. What used to be the military-industrial-media complex for a big part of the 20th century is a network of contractors for military staff, weapons, security services, information and individual products for the mass market. It has its own legal safeguards and business standards and is powerful enough to control and orient a big part of scientific research worldwide towards its own techno-scientific interests.

Take the example of DuPont, “one of the most successful science and engineering companies in the world” as it calls itself. With over 150 R&D facilities in China, Brazil, India, Germany and Switzerland, DuPont invests an average of $2 billion annually in a diverse range of technologies for markets including agriculture and nutrition (gmo seeds et al.), genetic traits, biofuels, automotive, construction, electronics, chemicals, and industrial materials. The company began in 1802 as a manufacturer of gunpowder, becoming the largest supplier to the US military in the American Civil War. Soon, it moved to the production of dynamite (proposing also its use in agriculture), bought shares in General Motors, and, as the inventor and manufacturer of nylon, played a major role in WWII production contracts for parachutes, powder bags, tires, as well as in the design and operation of the Hanford plutonium plant. Its bullet-resistant vests for the police and military, developed in the 1960s, are still being used today.

Interesting 19th to 21st-century stories showing up the links between war profits and the production of consumer commodities in “peacetime” can be told of numerous companies, even through a quick analysis of any name on a Forbes list of powerful players. The history and current operations of “beyond borders” companies, from IBM to Unilever to Bayer to Syngenta and Monsanto, to ICBC, Exxon Mobil, General Electric, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Royal Dutch Shell, HSBC, Samsung, Allianz, Daimler, AXA Group, Nestle, Mitsubishi, Google … weave a long web of mass exploitation, constant rounds of primitive accumulations, and targeted mass destruction across the planet.

Since the last quarter of the 20th century, these economic arrangements are tied to material production without even resorting to the excuse of some equivalence of “cost” to “labor”, but through relations of exploitation and war. They are supported by a very real but seemingly virtual and abstract system of banks and finance companies – that actually trade in a virtual, abstract commodity, magically a-chronic (since it projects its power into the distant future) called monetary value.

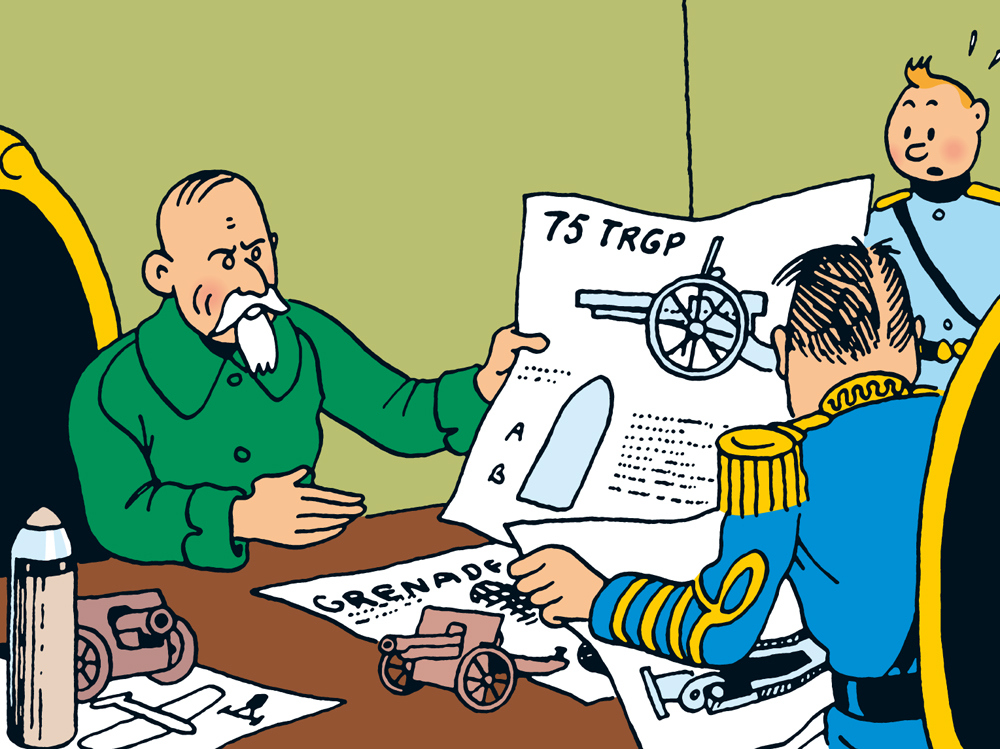

The most tragicomic aspect of the relationship between war and the economy remains this mysterious symbiosis of the ideology-free politics of money and death in the name of the nation. A good example is the Greek-Russian Basil Zacharoff (1849-1936), one of the richest men in his time. At the peak of his career as a world-class criminal, Zacharoff was trading in arms, owned newspapers, a bank and a Press agency. During WWI he did his best to accelerate the entry of Britain in the war (selling advanced weapons simultaneously to Brits, Germans and French)…His business was to make money and death circulate as widely, as steadily and as quickly as possible. At the same time, he was working as a multiple agent for both sides. He died knighted in Britain, decorated with the higher medal from the Legion D’ Honneur in France and the Cross of Salvation in Greece, having done business with all the above countries. He is now remembered officially as a great benefactor, who helped the Pasteur Institute, offered relief funds for the Corinthian earthquake victims in Greece and sponsored Chairs in literary Studies at Oxford and the Sorbonne.

IMAGE 7

In The Broken Ear (1937), the sixth volume of the Belgian cartoonist Herge’s Adventures of Tintin, Bazil Bazarof is an arms dealer supplying arms to both sides in a conflict, after having helped incite it. The character is a direct allusion to Basil Zacharoff.

8. the puzzle of anti-imperialism in the Middle East

During WWI, the notorious Lawrence of Arabia, an agent for the British Empire, invents and employs modern guerrilla theory and turns scattered elements of Arab nationalism into a full-blown political movement ready to face the Ottoman troops with whatever it takes. When, later, capitalist interests turn towards oil, the Middle East acquires a new importance.

The Office of Strategic Services, a wartime agency formed to coordinate espionage activities, and a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), organizes the first coup in the recently established States in the area. Husni al-Za’im, former officer in the Ottoman Army, and later officer in the French Army (after France instituted its colonial mandate over Syria), seized power in Syria in 1949 in the first military coup in the political history of the country, sponsored by the US. It was a “smooth transition” from Anglo-French colonial rule to a protectorate of European Powers, with a constitution copied from the French, and a clear attempt to both suppress all internal liberal voices for political and social change, and to secure control away from the Europeans.

ln the 1950s the CIA will support pan-Arab nationalism and help Gamal Abdel Nasser establish his presidency in Egypt, sending him advisors who will promote antisemitism, while the US, and all Western States, are pushing for the militarization of Israel. As nationalist Arab States are turning towards the USSR, the West encourages Israel to become a State of perpetual war.

The West will soon opt for islamist movements in Arab countries, hoping that religious ideology will replace an increasingly left-leaning Arab nationalism. In February 1979 Giscard d’Estaing, (after protecting the exiled muslim cleric and politician Ayatollah Khomeini at a villa in Neauphle-le-Château near Paris), sent the later “Supreme Leader of Iran” on a special flight to Tehran so that he could take control of the Iranian revolution.

Throughout the 1980s the US secret services support the islamist mujahedin against the Soviets in Afghanistan, and also back Iraq against Iran. In 1991, Iraq becomes an enemy, and, between 1992-1995, Iranian “guards of the revolution” fight in Bosnia next to the NATO troops against Serbian paramilitaries. After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, NATO cooperates with Iran both in Afghanistan and in Iraq – and today most of Baghdad is actually controlled by Iran. In Yemen, Iran cooperates with the Houthi who are fighting against the Sunnī government which is backed by Saudi Arabia, which in turn is supported by the West, which in Iraq is cooperating with Shīʿite Iran against the Sunnite fundamentalists and the remnants of the Baath Party, while in Syria the West is cooperating with the Sunni fundamentalists against Assad and with the PKK against the Sunnī in Syria and in Iraq.

The Western States cooperate with the Turkish State against the PKK, while the Turkish government also supports Hamas against Israel, which was selling weapons to Iran during the war against Iraq and also provided Pakistan with armaments that were then handed over to Afghani mujahedin in the war against Soviets in Afghanistan…

So in the 1980s the US government and its Western allies were clearly supporting Islamic fundamentalism one way or another…

“Divide and rule”, this has been the principle for the maintenance of warfare and chaos and the management of death in the Middle East, orchestrated by sequences of on and off alliances of Western and Middle Eastern governments.

One wonders, then, on what grounds do certain left movements see any prospect for liberation in the Islamic fractions of the Iraqi resistance, in Hamas, in Hezbollah, in Mahmoud Ahmadinejad…? One also wonders, on what grounds do some others see Israel as the “sole democratic force” in the region?

IMAGE 8

An official ceremony in Tehran on February 1, 2012, with guards carrying a cardboard Khomeini, representing the 1979 Air France flight sending Khomeini to Iran to “lead the revolution”.

9. the world war after the cold war: military liberalism and the new invisible dead

Projected on a global scenario, the war on Yugoslavia appears as the other side of the process of financial recolonization that has taken place in much of the world over the last decade, and the increasing subjugation of every aspect of life to the rule of money. By this rule markets have been introduced where previously there were commons, welfare provisions have been cut across the globe, workers’ entitlements have been reduced or eliminated, poverty has been imposed worldwide (…) This war that the World Bank, the IMF and other financial elites managing the global economy are waging, ultimately needs missiles and other deadly weapons, to keep people on course, producing for the global economy, at rhythms and retributions favorable to capital accumulation.

Massimo De Angelis and Silvia Federici, 1999

The War in Yugoslavia: On Whom the Bombs Are Falling?

http://www.midnightnotes.org/pamphlet_yugo.html

The “political economy” of an arms and military apparatus, detached from society and only sustainable via abstract labor, became independent of its original purpose. From the early-modern military despots’ hunger for money rose the principle of the “valorization of value,” which operated under the name of capitalism from the early 19th century. The rigid shell of military-statism was cast aside only to allow the now-independent money machine to progress as a pure end in itself within an “economy isolated” (Karl Polanyi) from all social and cultural shackles, and to give free reign to anonymous competition. This form of total competition bears the mark of Cain that bespeaks its origins in total war, even down to its terminology. It is no coincidence that Thomas Hobbes, founder of modern liberal state theory, declared the “war of all against all” as the natural human state. It was the proponents of the so-called Enlightenment who translated the imperatives of the “isolated economy” into an abstract philosophical ontology of the “autonomous subject” in the 18th century, which had nevertheless been predefined by the totalitarian value form.

Robert Kurz, The “Big Bang” of Modernity

The decade that followed the so-called “end of the Cold War” was marked by two “disciplinary wars”, one at the beginning, one at its closing. Hardly a month had passed after the fall of the Berlin Wall when, in December 1989, the US invaded Panama to arrest Manuel Noriega, military dictator of Panama from 1983 to 1989 and very close collaborator of the CIA since the 1950s in their secret war against the Sandinistas and against pockets of resistance throughout Central and South America, a war sponsored by drug trafficking.

In 1999 the NATO bombings “gave an end” to the war in former Yugoslavia. The most famous war of the decade is the first Gulf War which, as now many would agree, happened, at least partly, for the control of oil in the area.

In the same period, there began in Africa a series of mostly “unknown” wars for the pillage of natural resources. In this new “scramble for Africa”, there was no more competition amongst French, British, German, Belgian, Dutch interests as in the 19th century, what has been called “imperialism”. These were wars where all companies were making big and relatively secure profit. Agrochemical and pharmaceutical companies, mobile phone and mining companies, companies in the energy sector and arms companies from the G7-G8 countries were having a party.

The bloodiest were the war in Rwanda, that started in 1990 and culminated in the summer of 1994, with the massacre of half to one million Tutsis, the war in Sierra Leone (1991), that lasted a decade and left 50,000-300,000 dead, the war in Burundi (1993-2005) with 300,000, and the wars in Congo (1996-7), with 250,000-800,000 dead. The precise numbers of casualties will never be known, since these wars were never in the limelight, with the exception of the Tutsi-Hutu war, that proved “how inferior those blacks still are”, just like “those Balkan peoples, who for some reason still insisted on killing each other”.

The first Iraq war overshadowed those “crazy Balkan” wars and totally blocked the view to the peripheral wars – Africans seemed destined to die by the thousands. Yet the actual effects of the first and much celebrated hi-tech war in the history of humanity were also hidden by the blinding lights of publicity: 1,5 million Iraqis died from the famine and epidemics caused by the sanctions enforced by the West.

The decade after that did not bring the millennium virus for PCs, neither some spicy aftermath of the Clinton-Lewinsky affair. It was the decade of the War Against Terror, launched with the invasion of Afghanistan and of Iraq in 2003. Wars in Africa continued out of sight out of mind: The war in Congo intensified, a second civil war broke out in Liberia (with up to 300,000 dead according to estimates) and in Darfur, an armed conflict began that is still going on – with 178,258 to 461,520 dead (depending on the source) and almost 3 million displaced people.

During that same period another war broke out that would also go unnoticed for a long time. What the president Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) called the “war against drugs” was actually a war of the Mexican State and para-State apparatus against the population. 100-150,000 people have been killed in the last nine years. It seems that only the massive reaction and protests against the disappearance of the students in Ayotsinapa, with the creation of citizens’ militias and self-defense groups and the establishment of autonomous zones in Guerrero and Michoacán -until then only Chiapas had autonomous regions- were able to set up a kind of barrier against the State’s governance through extermination.

The Arab Spring in 2011 was first downplayed in the dominant media as merely the inspiration behind the “occupy” and “squares” movements in cities in the US, Europe and Israel. Yet in many ways, the Arab Spring was much more important. The Tunisian insurrection was particularly upsetting for supporters of the global status-quo, who watched demands for social justice emerging from self-organized structures from below, and couldn’t believe the revolutionary spirit of populations that had for decades been conditioned to channel all conflict towards authoritarian militarist solutions, towards Arab nationalisms, antisemitism and Islam. Very soon, the Arab Spring was crushed everywhere by the winter of militarism and fundamentalism: Attacks and civil war in Libya, the transformation of the popular insurrection into a conflict against Islamic fundamentalists and the military coup in Egypt, the civil war in Syria suppressed the memory of the hopeful and unprecedented uprisings of 2011 to near extinction.

In 2013 and 2014 the representation of wars in Syria and Iraq, as well as of the Israeli bombings in the Gaza strip were the tombstone of the Arab Spring, while the spectacular resurrection of an alleged conflict between State fascism and State anti-fascism, complete with hammers and sickles, Byzantine Eagles, nazi anti-imperialists and EU anti-imperialists served to show that capitalist peripheralism is the only alternative to capitalist globalization.

The number of migrants who lost their lives in the Mediterranean between 2014 and 2015 so far is greater than the total deaths in the Gaza bombings and deaths in the Ukraine war. Noone however seems willing to describe this as a war of civilized Europe against the victims of Western companies. Also, the huge sacrifice of lives in Syria only made it to the spotlight after the ISIL’s advancement in Iraq.

The war in Southern Sudan, possibly as deadly as the Syrian war, began in 2013 (after the official establishment of peace in Darfur). According to ICG data, it has cost the lives of 100,000 human beings. The war we have learnt not to lose our sleep over has inspired some minor box office hits, such as The Tailor of Panama, Hotel Rwanda, Blood Diamonds, Lord of War, The Constant Gardener. Even if these films (besides sentimental laundering) often speak the “uncomfortable truth” about the global system of domination, in the end their message comes with a warning: “Learn to live with your neuroses and insecurities, or else… this is what we do to the rest of the world.”

IMAGE 9

The character Yuri Orlof in Lord of War (2005) says: “Without operations like mine it would be impossible for certain countries to conduct a respectable war. I was able to navigate around those inconvenient little arms embargoes. There are three basic types of arms deal: white, being legal, black, being illegal, and my personal favorite color, gray. Sometimes I made the deal so convoluted, it was hard for me to work out if they were on the level.”

10. trophies of war as science and entertainment

Today’s war trophies look like well-built basketball players or exhausted travelers in migrant “reception centers”. In fact, Indians, Asians and Africans have been on show since the beginning of the modern colonial period.

Columbus brought some humans back from the New World to be studied in the Spanish Court. 16th century Vatican aristocrats like Hippolytus of the Medici owned, besides exotic animals, whole collections of different human races – Moors, Tartars, Africans and Indians.

19th century freak shows, with Siamese twins and microcephalic children, or the live exhibit in London and Paris of the “Hottentot Venus”, Saartjie Baartman, a South African Khoi-San Namaqua woman prepared the grounds for the 1870s mass spectacle of human zoos. They could be found in Paris, Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, Marseilles, Warsaw, New York and several US cities. In 1874, Greenland Eskimos were exhibited in the Hamburg Animal Park for the first time…In 1877, the addition of human Nubians and Eskimos to the Paris Jardin d’Acclimatation exhibition brought a profit of 57,963 francs to the organizers from the tickets of a record 985,000 visitors…(Africans and Inuits were soon to be accompanied by Lapps, Argentine Gauchos and others…) In Paris, over thirty ethnological exhibitions were organized between 1877 and 1912. Visitors kept going… The Parisian World Fair in 1889, displaying 400 indigenous people, was attended by 28 million other humans.

In 1896, to increase its visits, the Cincinnati Zoo invited 100 Sioux native Americans to live there for six months…Fine curiosities such as the Congolese pygmy Ota Benga at the Bronx Zoo in New York City was exhibited breastfeeding chimpanzee babies for a low cost ticket in 1906. The 1925 Belle Vue Zoo exhibit in Manchester displaying black Africans as savage beasts was entitled “Cannibals”…The human zoo tradition officially ends with the EXPO 58, the World Fair in Brussels, the de facto capital of the European Union

IMAGE 10

Poster for the Stuttgart “Show of the Peoples” during the “social-democratic” Weimar Republic in 1928.

11. anti-imperialisms

The final position of Marx and Engels on war is not at all straight-forward but perhaps in summing together the social and economic analysis we can get this picture: war is absolutely essential in the period of “primitive accumulation” in order to create the conditions of accumulation (especially the expropriation of laborers from the land) but with the establishment of a capitalist mode of production, war related expenditures become increasing antithetical to the accumulation process.

George Caffentzis

“Freezing the Movement and the Marxist Theory of War”,

In Letters of Blood and Fire, PM Press 2013, p. 214.

The world domination system is settling into its post-Cold War shape and new calls from the left and the right are urging the creation of anti-imperialist fronts. This revival of “anti-imperialism” feeds into the general confusion.

What has been called anti-imperialism has always been a rather vague concept, that was either connected to the dogmatic description of “imperialism [as] the highest stage of capitalism” (the title of Lenin’s famous booklet), or to struggles in the peripheries of capitalism sacrificing millions of lives to the national flag… Most crucially, it became a tool in the trade and diplomacy tactics of states and companies in the Eastern bloc. It served as the main argument for plunder, exploitation and oppression of the Soviet state, and later of the Chinese. Hundreds of thousands of red soldiers died for freedom in their states’ antagonism with the West.

In all its versions, anti-imperialism was closely tied to militarism, statist centralism and the cult of growth and development. Yet this “applied marxism” of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century was no misunderstanding, it was no abuse of the ideas of Marx and Engels.

In the mid-nineteenth century Marx and Engels saw a positive aspect to the planetary expansion of capitalism. In their view, with capitalist expansion, Enlightenment values and culture were also spreading across the world.

Industrial growth would create an industrial proletariat everywhere that would “pave the way for the Communists”. In the long run, colonialism would turn against capitalist interests, since, on the one hand the growth of commerce would force States to co-exist peacefully, while on the other, it would set the stage for international class struggles.

Engels would write about the French conquest in North Africa in the Northern Star, (22 January 1848): “Upon the whole it is, in our opinion, very fortunate that the Arabian chief has been taken. The struggle of the Bedouins was a hopeless one, and though the manner in which brutal soldiers, like Bugeaud, have carried on the war is highly blamable, the conquest of Algeria is an important and fortunate fact for the progress of civilization.”

Karl Marx, in the New-York Daily Tribune, August 8, 1853, wrote about British colonialism in India: “England has to fulfill a double mission in India: one destructive, the other regenerating[:] the annihilation of old Asiatic society, and the laying [of] the material foundations of Western society in Asia.”

The turn of European States towards expansion through war and military antagonism towards the end of the 19th century, (rather than through “peaceful conquest” or “constructive intervention”) proved Marx’s predictions wrong. Most marxist analysts, in need of a new theoretical framework, did not follow Rosa Luxembourg’s realization that the laws of the economy alone do not explain capitalism, let alone help overthrow it.

For Lenin it was exactly those laws of the economy that would inevitably lead to the bloody inter-imperialist conflict that in turn would lead to the collapse of capitalism. Lenin was fiercely critical of Luxembourg’s position that the struggle for national independence contradicts the struggle for emancipation. Leninist tacticist “scientific socialism” preferred to instrumentalize all national liberation struggles, along with all inter-imperialist oppositions, and to subjugate them to the state-communist master plan.

Both Lenin’s idea that capitalism would inevitably collapse under the weight of inter-imperalist conflicts, and Karl Kautsky’s belief that international cartels and the different national monopoly capitals will ultimately collaborate in a peaceful ‘joint exploitation of the world'”, were blown to pieces in World War II. After what for the governments was the “great”, “anti-fascist”, “patriotic” world war, the State anti-imperialists adjusted their views.

So the Soviets, and later the Maoists, proclaimed that in the 20th century the central conflict was no more between capitalists and workers, but between developed capitalist countries and dependent peripheral countries. For them, the task of anti-imperialist communists across the globe was to strive for “equivalence in primitive accumulation” and to promote national unity and industrial growth in peripheral countries.

This new “anti-imperialist imperialism” of state capitalism completed the expansion of capitalist relations across the planet. Exploited workers in peripheral countries first and foremost belonged to a nation rather than a class. National identity was the best tool for the control of local peripheral populations, and militarism the best way to “defend the revolution”.

Towards the end of the 1970s the “revolutionary plan” to “bring the conflict over to the capitalist West”, in order to fight “in the heart of the beast” (Jose Marti/Che Guevara) actually transferred the conflict to the opponent’s ground. Social movements (especially in Italy and Germany, the most significant movements at the time) became de facto subordinated to the activity of armed groups that directed political, social and cultural resistance towards an armed opposition between State mechanisms and small militarized formations based on ideology. The winner was easy to predict.

The Maoist “theory of the three worlds”, according to which China and India belonged to those nations that were being exploited by the superpowers and their allies, and in the name of which tens of thousands of guerillas across the world lost their lives, was turned into a diplomatic tool of public relations… It was the period in which the Communist Party of China was being transformed into what it is today. It managed to switch to a different model of totalitarianism without even having to change its name.

In sharp contrast, anticolonial struggle and antimilitarism, as inseparable aspects of anticapitalism and antistatism, have always been intrinsically connected in the thought and practice of anti-authoritarian, autonomous, libertarian and anarchist movements. The long history of Spanish anarchist organizing (1896-1939) is perhaps the most eloquent example. For anti-authoritarian movements (in Latin America before WWI, in the practices of the IWW in the US, in the councils of Bavaria, of Budapest, of Turin, of the Ukraine between 1918-1923, in German and Italian anarchist and autonomous and anarcho-syndicalist currents) imperialism was never the final phase where capitalism would be “historically fulfilled”. They could see: European colonialism, ever since the conquest of the New World, is the first stage in the global domination of capitalism.

IMAGE 11

“The New Vietnam” is the title of an article in a Greek (liberal) newspaper in 1995 presenting Greek volunteers in Bosnia (mostly members of the neonazi party) as anti-imperialist fighters in a “new Vietnam” against the US and the “New World Order”. Greek businessmen had been very quick to see there was profit to be made in the neighboring Balkan countries after the collapse of “communism”. Promoting ideological confusion was part of their strategy of economic intrusion. The construction company (ELLAKTOR) now building roads in Southern Serbia belongs to George Bobolas, owner also of the above mentioned newspaper, Ethnos, of Pegasus Publishing S.A.

12. the camp as a method of civilian management

The legal distinction between soldiers and civilians was introduced with the Hague Convention in 1899. Based on Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Lieber Code, (which had codified regulations regarding e.g. the treatment of deserters or parole to former rebel troops if they changed their mind and wanted to serve the nation), It defined the responsibilities and rights for each category, and also specified what kinds of weapons could be used “in any war between signatory parties”. It underlined the importance of an entity called international law.

International law was the premise established by the “civilized countries”, as the signatories of the Convention called themselves. They had been spreading war and mayhem across the planet, but now they were feeling uncertain about their own reproduction. It was time to create an environment more favorable to “peacetime” business, and hence to issue formal statements about what constitutes a “war crime”, and what is allowed under “martial law”.

All of the rules laid down by the first and the second (1907) Hague Conventions would be violated in the years to follow. Yet a long time before the German invasion of Belgium in 1914 “with no explicit warning” (in violation of the Convention), and before Germany’s introduction of poison gas (another such violation), months after this emblem of the will for peace and disarmament of the great powers, Britain, the winner of the Second Boer War, set up military concentration camps for civilians in South Africa, where black Africans (over 100,000) and Boers (27,927 according to reports) would lose their lives.

These South African concentration camps were not the first in the civilized word’s recent history: During the Spanish-American Wars in Cuba and in the Philippines, internment had been widely used. The US government’s mass detention and decimation settlements for the Cherokee and later for the Dakota Indians had been the initial inspiration for this new “camp movement” that was to become an evergreen fashion for the control of populations. However, the South African case was perhaps the first where extreme military practices targeted the whole population, became an integral part of official State policy, and soon became naturalized in public discourse. Refining Napoleon’s early biopolitics, detention camps now set an ideological example. They were at once military “direct action” and State “propaganda of the deed”. By the beginning of the next century, the army’s methods of handling POWs had become customary state practice for the management of whole populations. German camps in West Africa and later Italian camps in Libya would ensure standard performance of killing, violence and repression.

Now everyone agrees. War is the model for peace. The specialized, professional army is the model for governance.

Refugee camps today are intertwined with the tradition of the military management of civilians. For international law, they are considered humanitarian aid and are run by the UN, or NGOS such as the Red Cross. They can host up to tens of thousands of people, often for several years, and are very vulnerable to disease and epidemics.

Contrary to the myth that the West is “carrying a lot of the weight of refugee mobility”, 80% of displaced people, notably from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Liberia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, are in such “temporary settlements” in Africa and Asia. In a world where forced mobility is growing, an estimated 14 million people officially qualify as refugees, and many more as plain migrants. At the borders of Europe (and Australia, and the US…), their survival depends on pure luck.

IMAGE 12

A snapshot from the “left-majority” government of the Syriza-ANEL coalition in Greece: Hunger strike of migrants at the Paranesti “pre-departure center” near Drama, Greece, in April 2015, renovated with State and EU funds in early 2015.

summary and post-scriptum

Such a perfect democracy constructs its own inconceivable foe, terrorism. Its wish is to be judged by its enemies rather than by its results. The story of terrorism is written by the state and it is therefore highly instructive. The spectators must certainly never know everything about terrorism, but they must always know enough to convince them that, compared with terrorism, everything else must be acceptable, or in any case more rational and democratic.

G. Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, 1988

We have looked at several aspects of what we see as two dominant historical developments in the modern world: 1. the monetization of war: the transformation of primitive accumulations into a global evergreen business), the militarization of its economic relations (from the total labor separation of the army from other social activities in the 18th century that Robert Kurz describes, to the full development and refinement of mass killing from a distance in the “era of the drone”), and 2. the militarization of labor relations and of governance of whole societies: from the armies guarding the diamond mines, to the military style arrangement of mass production units, to the use of the concentration camp and the military defense of the border as a model for the management of whole populations – of people forced to move and flee from all kinds of war.

Ten years ago, Retort subtitled their book Capital and Spectacle in the New Age of War. One of the things we are trying to say here is that perhaps a pertinent way to describe the mental map upon which we see the dynamics of power operating today is through paraphrasing, and partly reversing, that subtitle: War and Capital are giving birth to a New Age (or rather a further stage) of Spectacle. The mutual encouragement and cross-fertilization of, on the one hand, capitalist relations (fetishizing the “expression of value” and the imposition of this abstraction by the sword, without socially creating value, as Anselm Jappe has explained in his Adventures of the Commodity) and, on the other hand, of modern warfare, constantly produce further separations within the bourgeois subject.

These separations (i.e. abstractive representations of social relations that, in terms of how a person understands the world, gradually disconnect labor from creating, understanding from producing meaning, experience from responsibility), solidify and naturalize what Debord called the Spectacle. The successive expressions of the Spectacle can be sought in the development of mass media regimes in the modern world, from the everyday newspaper to the cinema, to television, to web 2.0. – all of which are linked to representing war and are rooted in military technology (in the metaphorical and raw-material sense of the word).

Symbolized by the conceptual-cum-ideological poles within the bourgeois subject (peace at home / war abroad, fighting a war / reporting a war, news information about war / entertainment away from the warzone, populations worth living with privileges/populations that deserve to disappear, people who are useful / people who are not, watching on a screen / fighting on a screen, mass-communicating from a distance / mass-killing from a distance), give rise to the mass psychopathologies within the dominant human type of our times.

George Caffentzis has shown how the militarist legacy of anti-imperialisms is founded upon the premises of Marx’s “theory of war” – or lack of it. Instead of simply ideologizing the war-money power complex cutting up and through the planet, the struggle for life should be guided by the insistence on antimilitarism of autonomous and anarchist movements throughout recent history. Once again, there is no use resorting to the (traditionally, but not exclusively, left-wing) anti-imperialist worship of weapons and military struggle. Many realize by now that the culture of war leads society to the worship of death. Only by taking into account the structural narcissism of today’s simultaneous feeling of super-potency and confused powerlessness of the drone fighter, (a narcissism already present in the immersive disengagement of the online “social media” user), only if we grasp the concreteness and danger of a sense of self whose actions and imagination are divorced from creating reality (i.e. divorced from producing for society and making decisions for oneself and one’s community), could we start understanding the historical aspect of the emergence of the self-destructive individual willing to take as many others as possible down with them to their grave, merely in exchange for a flash of imagined post-mortem publicity.

After the murderous attacks on Friday 13 November 2015 in Paris, anticapitalist circles seemed to agree on the general evaluation that “it is imperialism that should be blamed”, or, more precisely, that Western citizens are now confronted by the consequences of their own countries’ imperialist politics. Let us note here that this period is technically not the most violent in the history of capitalism – not from the standpoint of military expansion nor of rounds of primitive accumulation. Even in recent times, there have been bloodier episodes in France itself. In the 1960s France was at (colonial) war with Algeria and with its own citizens: On October 17, 1961, the French Police attacked an “illegal demonstration” of some 30,000 pro-National Liberation Front (FLN) Algerians, “killing 70 to 200 Algerians and throwing dead bodies and wounded people in the river Seine, from the Saint-Michel bridge”, according to officially accepted accounts. Yet back then, nobody thought of blowing themselves up in response. And this was not due to tighter border controls. As our friend Ernie Larsen points out, “in the midst of the anti-colonial war(s) people never detonated themselves—that now strangely familiar brew of fanaticism and religiosity would have been rightly seen as reactionary in the 60s. Militants were prepared to sacrifice their lives in the midst of struggle, if necessary—this we could say perhaps marks the border between passion and fanaticism.”

Some analyses talked of an “inside provocation” within the general chaos of capitalist destabilization, of a conscious decision by para-State circles to spread more terror in order to impose stricter control measures. But here there seem to be no analogies whatsoever with the Piazza Fontana case… The question “qui bono?”, i.e. who benefits from the attacks?, (the answer to which is initially Russia, but more might take advantage) does not help in answering the question “who is responsible”.

There is no certainty as to the consequences of any action at the moment within this broader scheme of chaos and confusion in the geopolitical arena. The only thing that has emerged as a given fact in the last quarter century, is that after the end of Cold War, global capitalism definitely chose “the islamic threat” as a replacement for “the communist threat”, while before it had collaborated with Islam against the State capitalism they called “communism”.

Sometimes scarecrows are effective as mere scarecrows, sometimes though they morph into a self-fulfilling prophecy, against the will of their own creators. Capitalism as a system might not be under threat, yet the dominant relations between its ingredients definitely are – and many die in the process. The state of siege that many global cities find themselves in today might not have been intended by the global system of domination, however chaos can be managed to its benefit: The State of Israel for example has for decades reproduced itself through an economy of permanent war and a society of total control. It seems that it would immediately collapse without internal enemies like Hamas or Hezbollah. However: While a “global Israel” might indeed be a fully sustainable model, since it can infinitely reproduce its polarities through permanent warfare, we are by no means implying that a conscious decision has been made by the ruling classes to implement such a model worldwide. To do so would be vulgar conspiracy theory – which in fact quite a few people, left and right, feel comfortable subscribing to.

Many feel ISIL chose France this November as the “the heart of the Enlightenment itself”. Such interpretations say more about the mindset of the people expressing them, than about the actual motives of ISIL. Many European citizens might still be proud of the European cultural tradition, yet for the countries of the capitalist periphery, the European continent stands for colonialism, not Enlightenment values. Enlightenment supporters indeed advocated the abolition of slavery, yet the “superiority of the European race” and “of our civilization” was for two centuries the basic ideological foundation and political argument of colonial plunder. Furthermore, it looks like the Paris attacks were not addressed to the “periphery”, they were primarily an appeal to all those in the West “ready to die in the new holy war”.

Others have stressed the need to “at last do something about Islamists, beyond all that political correctness about religious tolerance”. Yet even if religion has no doubt been the classic form of false consciousness, never have religious wars broken out for religious reasons. In the specific case of ISIL attacks, most of the perpetrators have not even been raised within an Islamic social context: The construct of “jihadism” was presented as the Absolute Evil by the very society they were born and bred in (in other words, in a European country) and they simply chose to go against this society. The ultra-violence of these self-destructive fanatics is indeed a horrific threat, yet it is not Islamic at all… The society of the spectacle reaches its ironic peak: Facebook, youtube, Dabiq (ISIL’s glossy propaganda “instrument”, actually just another lifestyle mag set up with Adobe’s latest InDesign)… all become ingredients in a dystopia crammed with images, allegedly promoting the most anti-representational, un-iconic, iconoclastic religion!

Let us repeat some basic banalities. The Arab Spring was followed by dictatorships and wars in Egypt, Libya and Syria. In Syria, bloody proxy wars were fought in search of a new balance of global power. It is common knowledge that the West played a decisive role in the creation of ISIL and in its supply with weapons and equipment, that it tolerated ISIL as it was growing, and that it sponsored it through partaking in its illicit oil trade. It is common knowledge that most of its basic actors were born and raised on European soil.

In recent times there has been a lot of suicide-bombing activity in the periphery, familiarizing populations in Lebanon, Turkish Kurdistan, Palestine and elsewhere with everyday killing and destruction. Suicide bombers in the West become familiarized with death through the everyday plight of survival in capitalism. On the facebook page of one of the suicide bombers there were photos of the 2007 riots in the Parisian banlieues. He deleted his own “profile”, just as the dominant language deleted the meaning of those riots. The call for jihad through the so-called social media is a call for an essentially meaningless act, it is the virtual celebration of a desperate, ecstatic moment of death and mass killing, fast and glorious, with no future and no perspective. Today’s suicide attacks have more in common with school shootings in the US than with the armed activities of e.g. palestinian organizations in the 1970s.

Lives are not numbers and life cannot be counted. Yet numbers can speak volumes about today’s “culture of death”. The number of people who have lost their lives in attacks in Madrid (2004), London (2005) and Paris (2015) by perpetrators who were mostly Europeans, is comparable to the number of victims of shootings at schools and colleges in the US during roughly the same period. In 2015 alone, there have been 35 such attacks in schools, over 1,000 people have been killed by cops’ bullets since January 2015, while mass shootings by “disturbed” killers in the US since 2006 have claimed the lives of reportedly 1431 people.

Even if the territoriality of ISIL were annihilated, even if its material basis were fully exterminated, there is nothing to guarantee an end to the production of suicide bombers. Capitalism mass-produces emptiness. The periphery does not even expect “inclusion” or “growth” anymore. In a world of globalized despair, so-called “social media networking” is taking the concept of integrated spectacle, that Debord analyzed in his 1988 Comments, to its logical explosion.

Twenty years ago, capitalismus invictus was forcefully challenged by the first real-life “cyber-guerilla”: The black flags and red stars, the head covers and the new hope of the Zapatista revolution were a real threat to the alleged invincibility of the system. The song of life interrupted the soporific lullaby of the Spectacle.

Today the dominant powers across the world are trying to convince us that ISIL’s black flags and hoods are the actual Absolute Evil, yet it is too obvious that ISIL is singing the same deadly tune as they are. It is frightening to see how the notions of “global networking” and “horizontality” could get so distorted, notions that once rose out of the Lacandona Jungle and the Movement for Social Justice… Horizontal networks of killing cultivated via facebook are rapidly reversing the idea that “anyone can be wearing the hood”. For the EZLN it is anyone who cannot accept subordination, devaluation of life, and compromise – for the jihadist mutation it is anyone who is willing to trade a meaningless life with a meaningless- but spectacular- death.

Geopolitical scenarios, conspiracy theories, anti-imperialist rhetoric… none of it will work. The Party of Death can only be fought with collective resistance, personal creativity and solidarity, with the constant refinement of a social, full-hearted, life-affirming gesture.

Texts / links used and referenced

Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Eric Deroo, Sandrine Lemaire, Zoos humains. De la Vénus hottentote aux reality shows, La Découverte 2002

Iain A. Boal, T. J. Clark, Joseph Matthews, and Michael Watts, Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War, Verso 2005

George Caffentzis In Letters of Blood and Fire: Work, Machines, and Value, PM Press 2013

Grégoire Chamayou, Théorie du drone, La fabrique, 2013

Massimo De Angelis and Silvia Federici, “The War in Yugoslavia: On Whom the Bombs Are Falling?”: http://www.midnightnotes.org/pamphlet_yugo.html

Guy Debord, Commentaires sur la société du spectacle, Éditions Gérard Lebovici 1988

Anne Dreesbach, Colonial Exhibitions, ‘Völkerschauen’ and the Display of the ‘Other’, Mainz Institute of European History, 2012

Silvia Federici, “War, Globalization, and Reproduction” 2001: https://www.nadir.org/nadir/initiativ/agp/free/9-11/federici.htm

Irene L. Gendzier, Notes from the Minefield: United States Intervention in Lebanon and the Middle East, 1945–1958. Columbia University Press 1997

André Gerolymatos, Castles Made of Sand: A Century of Anglo-American Espionage and Intervention in the Middle East, Thomas Dunne books, MacMillan 2010

Dave Grossman, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Back Bay Books (1996) 2009

Derek Gregory, The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq, Wiley-Blackwell 2004

Christopher Ingraham, “There are now more guns than people in the United States”, The Washington Post, 5 October 2015

Anselm Jappe. Les Aventures de la marchandise: Pour une nouvelle critique de la valeur, Denoël 2003

Robert Kurz, “Mit Moneten und Kanonen: Innovation durch Feuerwaffen, Expansion durch Krieg: Ein Blick in die Urgeschichte der abstrakten Arbeit”, Jungle World, 3, 9 January 2002

Douglas Little, “Cold War and Covert Action: The United States and Syria, 1945-1958”. Middle East Journal 44 (1) 1990

S.L.A. Marshall, Men Against Fire: The Problem of Battle Command, University of Oklahoma Press (1947) 2000

Peter Mason, The Lives of Images, Reaktion Books 2001

Renae Merle, “Census Counts 100,000 Contractors in Iraq”, The Washington Post, 12 May 2006

Midnight Notes Collective (eds) Midnight Oil: Work, Energy, War, 1973-1992, Autonomedia 1992

Jan Mieszkowski,Watching War, Stanford University Press 2012

Sherry Millner and Ernest Larsen, Scenes from the Microwar [self-produced video] 1985

Martha Lizabeth Phelps, “Doppelgangers of the State: Private Security and Transferable Legitimacy”. Politics & Policy 42 (6): 824–849, December 2014

P.W. Singer, Corporate Warriors: The Rise of Privatized Military Industry, Cornell University Press | Cornell Studies in Security Affairs 2003

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Trends in World Military Expenditure”, April 2015: http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/recent-trends

Richard Wormser, “D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation 1915”: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_birth.html