Damjan Pavlica

This research focuses on the Yugoslav history of Kosovo in the 20th century, especially on the Serbian-Albanian conflict. I wanted to find out how Kosovo entered Yugoslavia and how it left. I endeavored to acquaint myself with the views of Serbian/Yugoslav, Albanian, Western and other authors and discovered that, as is usual with ethnic conflicts, the truth is never one sided. Dominion over Kosovo changed hands a few times, and the violence of the dominant group always bred more violence, often against the group that had lost its dominant position.

The goal of this work is to contribute to a greater understanding of the Kosovo problem in Serbia and shed light on certain lesser known aspects of its history.

Kosovo Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire

In the beginning of the 20th century, the Kosovo Vilayet was a province of the Ottoman Empire whose territory was significantly larger than the territory of today’s Kosovo. It included the whole of Kosovo, Sandžak, Preševo Valley and Western Macedonia. The capital of the Kosovo Vilayet was Skopje. The majority in Kosovo were Albanians; Serbs were the majority in the Northern Kosovo, while they were a minority in other parts, especially in the South. The situation in Kosovo, like in other parts of Turkey, was especially difficult for the Christian minority.

The diplomacy of the Kingdom of Serbia began to portray the cases of violence and oppression against the Serbs in a way that would make the Albanians seem as savages which Serbia needs to subdue. In Serbia, people began to see the Albanians as usurpers of Serbian land, forgetting that the Serbs had moved massively from Kosovo during the Great Migration to Hungary. Serbia asserted its “historical right” to Kosovo because it was part of the Rascia State. From 1904 onward, Serbia began to send Chetnik units to Kosovo whose clashes with Albanians meant that the Serbs living there suffered. The representatives of Kosovar Serbs opposed the sending of armed troops, asking the Serbian government to stop them as they were the cause of even more violence against their people. Serbia’s Chetnik action also met strong resistance from Austria-Hungary which considered this policy as Great Serbian.

In the beginning of the 20th century, Kosovo was the center of the Albanian national revival and the fight for liberation from the Turks. From 1905 to 1912 Albanians organized a number of uprisings with the goal of acquiring cultural, economic and political autonomy. The Albanians’ armed rebellions were regularly stifled in blood by the Turks, until in 1908, the Young Turk Revolution occurred. At first supported by the Albanians due to the promise of autonomy, decrease in taxes and improvement of general living conditions, the Young Turks eventually consolidated their power, established strict centralism, instituting Turkish as the only language of administration. This lead to an eruption of dissatisfaction and an armed rebellion in Kosovo in June 1909. The first armed clashes with the new authorities happened in the vicinity of Đakovica, and in the spring of 1910, an uprising of larger proportions happened in the Kosovo Vilayet. The rebels were also supported by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization which fought for Macedonian autonomy. Seeing that the rebellion was developing, the Young Turk authorities sent a punitive expedition from Skopje which stifled the rebellion with bloodshed in a 3-day battle from May 11th to May 13th in 1910, not sparing neither women, children or the elderly. Already in the beginning of 1911 there was a new armed rebellion in Kosovo as well as Northern Albania. The main demand of the rebels was the recognition of the Albanian nation, along with autonomy: economically, administratively, culturally and militarily. This rebellion was stifled in August 1911.

In the beginning of 1912 the Great Albanian uprising took place under the leadership of the General Insurrection Committee in the areas of Drenica, Peć, Đakovica and Northern Albania. The leaders of the rebels were Isa Boljetinac, Hasan Prishtina, Bajram Curi among others. The rebels sought the establishment of an autonomous Albania, the retreat of Turkish officers and the introduction of Albanian as the official language. They immediately took over many towns, including Đakovica, Mitrovica, Vučitrn and Prishtina in order to then quickly gain control of all of Kosovo, Northern Albania and Skopje. Due to the success of the Albanian rebellion, the Young Turk government decided to retreat. After the Albanian rebels reached Thessaloniki, the new government was forced to meet all their demands. An autonomous Albania was recognized on August 18th 1912 which included four vilayets: Kosovo, Skadar, Janjin and Bitolj. The neighbors saw this as the creation of a “Great Albania” as the inhabitants of these areas were not all Albanian. This threatened the national interests of the neighboring countries which held pretentions to these areas, and they quickly went to war with Turkey.

Before the war itself, on October 19th 1912 there was a meeting of the leaders in Skopje, the seat of the Kosovo Vilayet. It was decided that the Albanians would defend the territories they considered theirs in the upcoming was, fighting on the side of Turkey.

The annexation of Kosovo in the Balkan Wars

The Serbian and Montenegrin armies attacked the Ottoman state in October 1912, penetrating to Kosovo and Metohija. Albanians resisted the taking of their settlements and organized volunteer units which carried out an armed resistance against the actions of the Serbian troops. A bigger battle happened at Podujevo as 15,000 volunteers under the command of Isa Boljetinac stood against the Third Serbian Army without success. The Serbian Army then conquered Prizren and a larger part of Albania with the Littoral.

During the Balkan Wars, Serbia annexed the areas of Sandžak, Macedonia, Kosovo and briefly also Albania. Serbs didn’t form the majority in these areas which posed a problem for Serbian diplomacy which presented the conquest of Kosovo as a liberation from Turks, disregarding the fact that the make-up of the population had changed over the ages. At the peace talks in London, Serbia refused to be satisfied with just Northern Kosovo, for which it would, by the irony of fate, be asking for a century later. After the end of the war, the Kosovo-Metohija areas came under Serbia and Montenegro, which Serbian historiography calls liberation and Albanian calls occupation. From the viewpoint of political science, the appropriate term is annexation, as it was done without the agreement of national representatives and without a referendum for the population.

“Houses and whole villages have been turned to dust, unarmed and innocent inhabitants have been massacred on a large scale, unbelievable acts of violence, pillages and cruelties of every kind – these were the measures that were taken and are still being taken by the Serbian-Montenegrin Army, with the goal of the complete alteration of the ethnic character of areas populated exclusively by Albanians.” – From the Report of the International Commission on the Balkan Wars.

In those years there was plenty of talk on the “Kosovo Vengeance” for 1389 which was magically flown from the Turks to the Albanians. This policy met criticism from the European press which wrote about the crimes of ethnic cleansing done by the Serbian and Montenegrin troops during the occupation of Albanian settlements. According to reports, the suffering of the inhabitants of Prishtina, Ferizović (later Uroševac), Đakovica, Prizren and certain other towns was especially great. In Austria, the belief that Serbia had taken too much prevailed.

Serbian oppositionist Dimitrije Tucović warned that “an attempt at murder is taking place with the design against an entire nation” which is “a criminal act” for which “reparations must be made”. Tucović was against the territorial expansion of Serbia and advocated that Kosovo enter the Balkan Federation with Serbia and other areas on an equal level. “The boundless hostility of the Albanian people against Serbia is the first positive result of the Albanian policy of the Serbian government. The second, even more dangerous result is the strengthening of two great powers with the biggest interests in the Western Balkans.”

Tucović meant Italy and Austria-Hungary, and the latter, with a good motive, attacked Serbia in order to conquer it in 1915. The drastic worsening of the relationship with the Albanians was paid dearly by the Serbian Army and the columns of refugees during the tragic withdrawal across Kosovo and Albania, remembered as the “Albanian Golgota”.

But, due to very unusual unfolding of events, Serbia found itself on the winning side at the end of World War I, and it was granted not only the territorial expansions from the Balkan Wars, but also the right to create a great Yugoslav state. And while Serbs had fought for Kosovo to become part of Serbia, it instead became part of Yugoslavia.

The colonization of Kosovo in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

“Serbia gained Kosovo, but also a millstone around the neck of its development.” – Leon Trotsky, correspondent from the Balkan battlefield

After World War I, Kosovo became part of the newly-founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Kosovo became a Serbian colony, and it was mostly governed by a military command. Serbian politicians had no plan whatsoever that would also include the interests of the Albanian population. The belief predominated that Albanians had to be relocated and Serbs moved in.

In the Inter-War period, the Belgrade government carried out a comprehensive plan of colonization with the goal of changing the ethnic structure of Kosovo in favor of Serbs. An advantage in moving was given to ex-soldiers and members of Chetnik units. By 1941, 60,000 colonists were moved there, often to properties taken from Albanians. Over 90% of the total number of colonists were Serbs from various parts of Yugoslavia (this also included Montenegrins then). Taking away the houses from Albanian peasants in order to give them to colonists caused a hatred towards the colonists, and left permanent consequences in the relations between Serbs and Albanians.

Colonization by counties

Uroševac: 15,381 colonists

Đakovica: 15,824 colonists

Prizren: 3,084 colonists

Peć: 13,376 colonists

Mitrovica: 429

Vučitrn: 10,169

All: 58,263

With the colonization, completely new settlements were also formed in Kosovo and Metohija, such as: Kosovo Polje, Obilić, Hercegovo, Orlović, Devet Jugovića, Lazarevo, Svračak, Novo Rujce, Staro Gracko, and many others.

In parallel with the Serbian colonization, there was also a process of forced relocation of Albanian inhabitants. According to the data of the Historical Institute in Prishtina, from 1919 to 1940, 255,878 Muslims were relocated from Yugoslavia to Turkey, 215,412 of which were Albanian.

Albanian rebels, the Kachaks, fought against the establishment of Serbian authority on territories populated with Albanians. There were plenty of them in woods and mountains, and they held actual authority over villages for years. Their political wing was the Kosovo Committee which advocated the secession of Albanian-majority areas from the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and unification with Albania. The most influential of the Kachaks were Azem Bejta and his wife Shota Galica who became heroes for the Albanian population because of their fight against state terror. The Belgrade government carried out extremely harsh measures against the breakaway Albanians; their possessions were taken away and given to colonists, their relatives were interned, and whole villages punished if they had helped them. The taking of land led to rebellions of whole villages. The villages from which rebellion had erupted were taken by the Army with heavy artillery. According to the data of the Historical Institute of Prishtina, the Army set on fire and destroyed 320 Albanian villages between 1918 and 1938.

In the 1930s, the belief prevailed that the gradual colonization of Kosovo was ineffective. Vasa Šaletić, the commissioner for colonization, claimed that Albanians had to be moved to Turkey immediately and that “moving of Serbs into the midst of half a million Albanians had been a mistake.” The Yugoslav authorities held a meeting of certain ministries and the General Staff in 1935 at which the project of “moving non-Slavic elements from South Serbia to Turkey” was planned. In the beginning of 1936, Turkey expressed the willingness to make a deal with Yugoslavia on the relocation of 200,000 inhabitants “who have a similar mentality to the Turks and would easily assimilate”.

In 1937, the Serbian academician Vaso Čubrilović created a project of a quick solution to the “Albanian problem” with the massive ethnic cleansing of Kosovo for Stojadinović’s government: “The Arnauts are impossible to repress merely by gradual colonization…The only method and the only measure is a brutal force of an organized state authority, in which we have always been above them.”

Professor dr. Vaso Čubrilović planned in detail the methods of ethnic cleansing, which include the creation of a mass psychosis, giving weapons to colonists, sending armed Chetniks, state repression, arrests, unpaid labour, abolishing work permits, firing people from their jobs, cutting down woods, shrinking of cemeteries, burning settlements and similar.

From July 9th to July 11th 1938 a meeting was held in Istanbul between Yugoslavia and Turkey on the preparation of the agreement on relocation of Albanians. The sides agreed to relocate 40,000 Albanian families from Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro into barren lands in Anatolia within 6 years. According to the agreement, families could have more than 100 members, so 40,000 families could technically mean millions of people. The article 2. of the Convention assumed a complete repatriation of Albanians from towns such as: Prizren, Uroševac, Prishtina, Kačanik, Gnjilane, Preševo, Peć, Istok, Mitrovica, Đakovica, Vučitrn, Drenica and others.

In January 1939, Ivo Andrić, the ambassador of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Nazi Germany created a project of the division of Albania between Yugoslavia and Italy for Milan Stojadinović. Andrić tried to prove that the assimilation and relocation of Albanian will be easier if Albania is abolished:

“By dividing Arbania, an attractive center for the Arbanian minority in Kosovo would disappear, and it would assimilate more easily in the new situation. We would eventually get 200,000 to 300,000 Arbanians, but they are mostly Catholics whose relationship with Arbanian Muslims has never been good. The question of relocating Arbanian Muslims to Turkey would therefore take place in new circumstances, as there would be no stronger action to prevent it.”

The Communist Party of Yugoslavia opposed the relocation of Albanians to Turkey, taking away their land, and carrying out terror against them. The Communists believed that the annexation of Albanian places has created a conflict with them, and supported their right to self-determination.

The ratification and introduction of the Yugoslav-Turkish Convention was disturbed by financial problems, an Albanian campaign against relocation and the break-out of World War II. With the Second World War the results of decades-long colonization of Kosovo were annulled. The colonization with which the “historical injustice” of the ethnic loss of Kosovo was tried to be made right not only failed, but showed itself to be extremely harmful to Kosovar Serbs.

The ethnic division of Kosovo in World War II

“The Serbian population of Kosovo must be moved as soon as possible…Serbian colonizers must be killed.” – Occupation PM of Albania Mustafa Kruja in 1942.

After the occupation and division of Yugoslavia in 1942, Italy joined the largest part of Kosovo with Albania, except the North which the Germans joined with occupied Serbia, and a smaller southwestern part which was taken by Bulgaria. The Italians portrayed themselves as liberators in Kosovo, introduced the Albanian language in administration and education, and allowed the use of the Albanian flag. They formed Albanian quisling formations. The persecution of Serbs, mostly colonists, was cruel. The Serbian and Montenegrin colonists were driven back to Montenegro and Serbia, many were killed, their possessions stolen, and houses burnt. The Chetnik units of Kosta Pečanac carried out retaliations for killed Serbs against the Albanian population of border villages.

In the beginning of the war, Kosovar Partisan units were mainly formed of Serbs and Montenegrins, as the Albanians didn’t want the revival of the Yugoslavia into which they had been forced. The first Albanian Partisan units were formed in the fall of 1942. The Kosovar Partisans Boro Vukmirović and Ramiz Sadiku who died in April 1943 later became symbols of Brotherhood and Unity. In January 1944, the Buje conference is held at which the National Liberation Council of Kosovo decides to join Kosovo with Albania. In the middle of 1944 there is a mass Partisan uprising and 7 Kosovo-Metohija brigades are formed.

The decision of Kosovar Partisans to join Kosovo with Albania of course wasn’t carried out. After the withdrawal of the German Army, Yugoslav Partisans enter Kosovo in November 1944. Ten days after Partisan units enter Kosovo, in December 1944, there is a massive uprising of Albanians who saw this as another “occupation” of Kosovo. The Central Headquarters of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia sent over 30,000 soldiers to stifle the “ballistic[1] uprising”. In putting down the Kosovar revolt, two brigades of the National Liberation Army of Albania also cooperated, due to a deal of Broz with Hoxha. The hardest battles took place in Drenica, and after that in Uroševac, Gnjilan and Mitrovica. Many Albanian Partisans saw the new annexation of Kosovo to Serbia as the annihilation of their fight and a betrayal by the leadership of the National Liberation uprising.

Post-war (Ranković) period in FNRJ

On February 8th 1945 in Kosovo, a Military administration is established, in March the main resistance of Kosovar Albanians was broken, but fighting still continued over the next months. After the establishment of Yugoslav control of Kosovo, there was a chaotic return of the Serbian and Montenegrin colonists who were driven out, while vengeance and retributions were carried out. Because of this, the new authorities of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia on March 6th 1945 made the decision to temporarily forbid the return of colonists. This remained in effect until the implementation of the Law on revision of colonial relation in August of the same year, after which 3,352 “ex colonists” acquired the right of return to Kosovo and Metohija, while 306 settlers who lost the right of return, were directed towards Vojvodina.

On July 9 1945, the new Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija decided to declare the Autonomous Kosovo-Metohija Land, declaring that the population wishes that this land be annexed to “Federal Serbia” as its constituent part. Shortly after, at the third AVNOJ meeting on August 7 1945, Kosovo is annexed to the People’s Republic of Serbia. Professor Jovan Đorđević claimed that Kosovar autonomy was not the creation of the People’s Republic of Serbia, but had been a category of the constitutional law of Yugoslavia from the very beginning, which was assumed and guaranteed by the federal constitution. Between Kosovo and Serbia there had been no hierarchical laws nor has there been any twofold responsibility. All Kosovar government organs executed their rights independently and were responsible for their work only to voters, respectively the Provincial Assembly and the Regional Council.

Even after 1945, there were groups of ballists who wouldn’t recognize the decision to annex Kosovo to Serbia. Against them, the units OZNA and UDBA were engaged; they held de facto authority over Kosovo. The situation of Albanians in the new Yugoslavia was drastically worsened after the Informbiro Resolution in 1948 when many Albanian intellectuals were locked up or liquidated on accusation of being Enver Hoxha’s spies. In 1951 the question of relocation of Albanians was brought up again and new negotiations with Turkey took place. It seemed that the state security service pressured the Albanians to claim they were Turks at the census. Within only 5 years, there was a drastic increase in the number of people who claimed they were Turks in Kosovo, from 1,315 (in 1948) to 34,583 (in 1953).

The Kosovo state security service treated Albanians as a suspicious element, and it was mostly made up of Serbs and Montenegrins. In 1955-1956, the state security service with Ranković as its head carried out an action of taking away arms and systematic raiding of homes, the harshness of which went beyond every reasonable line and amounted to terror against the population. Under the excuse of seeking weapons, the organs of state security tortured thousands of people, of which about a hundred died. The repressive policy against Kosovar Albanians continued all the way until Aleksandar Ranković was replaced in 1966.

The development of Kosovar autonomy in SFRY

“During my youth, I believed that Yugoslavia could survive as a federative multiethnic state of equal nations. I was honestly a fan of the project of Yugoslavia according to the 1974 Constitution. We were somehow proud that Yugoslavia was different from all the countries with rigid communist regimes, with no freedom whatsoever, and with poor citizens. We citizens of Yugoslavia lived better lives in every sense. I thought that in the frame of such a project, my Albanian nation could also do well.” – Kosovar politician Azem Vlasi

The chief of Yugoslav security Aleksandar Ranković was replaced at the Brioni Plenum in 1966. At the same time, the 1966 constitutional amendments recognized the provinces as “constitutive elements of the federation” with which Kosovo gained the elements of statehood. Despite the fact that Albanians were the majority population of the province, Serbs and Montenegrins held a disproportionately high number of state and party functions, including control over the local police and security forces. On November 27th 1968 there was a mass student demonstration in Kosovo which started at the Faculty of Arts in Prishtina. Only after that, Kosovar Albanians gained certain autonomy, including the right to schooling in their own language. In November 1968 the name of the province is changed to Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, with which Metohija (a monastic occupancy) was removed from its name.

With the Constitution of 1974, Kosovo gained wide autonomy and the status of a federal unit of the SFRY. With the acquisition of real autonomy, Serbs and Montenegrins ceased to be the dominant minority. Albanians started taking over leading positions from many Serbs in political bodies, administration and labour organizations. With the principle of ethnic representation, by which the percentage of the employed members of a certain nation had to be in alignment with the ethnic structure, many Serbs and Montenegrins lost their jobs. At the same time, many Albanians who were deported during the course of the Kingdom period returned, while at the same time there was also immigration from Albania to a better life in Yugoslavia. Faced with losing their jobs, and often unfriendly environment, Serbs began massively leaving Kosovo. According to certain percentage data (New York Times, July 12 1982) during the 1970s around 70,000 Serbs moved from Kosovo. During these years, many Serbian monasteries complained about damage done by strangers, the illegal cutting of woods, and similar problems.

Protests of Albanians and demands for a republic

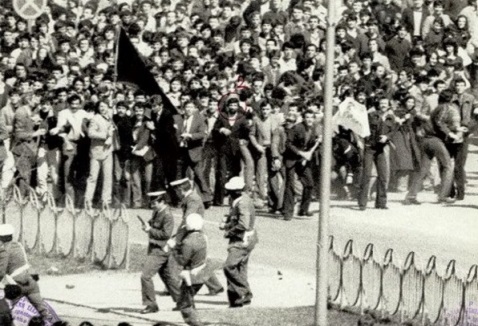

After Tito’s death, among Albanians, who formed the absolute majority of Kosovo’s population (77.4% according to the 1981 census), the fear started spreading that Kosovo could fall under Serbian administration again. There was a belief that the only way to prevent this was for Albanians to be granted the official status of a nation and their own republic which could never fall under Serbian rule again. Students of the University of Priština started peaceful protests in March 1981 which soon became nation-wide, demanding equal position of Albanians with the other, Slavic nations in Yugoslavia, which had their own republics. With the slogan “Kosovo Republika!” they wanted Kosovo to become the seventh republic of the Yugoslav federation and for the Yugoslav authorities to cease to treat them as a national minority (so-called nationality), but to recognize them as a nation.

The Yugoslav authorities responded to these demands by sending the Army to deal with the demonstrators. In the riots that followed, tens of Albanian pupils and students were killed, which the regime then hid from the public. After the bloody suppression of the demonstrations, there appeared a great division between Serbs and Albanians – Serbs demanded the abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy while Albanians demanded statehood. A certain type of military administration was established in Kosovo, and Albanians were subjected to repression and mass arrests. Also, there was violence against Serbs.

In the following years, many Albanians are sent to prison for numerous years, mostly because of expressing the demand for Kosovo to become a republic.

Protests of the Kosovar Serbs and a campaign about genocide

After the Albanian demonstrations, Kosovar Serbs in 1982 (led by Kosta Bulatović, Miroslav Šolević and others) started to complain about “perfidious pressures from the positions of the state”, and the center of the movement became Kosovo Polje, which used to be a Serbian colony. At the same time, an anti-Albanian campaign started in Serbia whose central theme was “genocide” against Serbs in Kosovo, and which portrayed the migrations of Serbs as planned ethnic cleansing carried out by the province’s leadership. In April 1982, 21 priests of the Serbian Orthodox Church, among which were certain future bishops (Anastasije Jeftić, Irinej Bulović, Amfilohije Radović) appealed to the highest church and state organs with the “Appeal for the protection of the Serbian population and its holy objects in Kosovo and Metohija”, which spoke of the “planned genocide against the Serbian nation” and actualized the Kosovo Myth[2]. In 1983 the church newspaper Pravoslavlje (Orthodoxy) publishes a feuilleton by Anastasije Jevtić called “From Kosovo to Jadovan” which describes cases of “brutal and bestial rapes of Serbian women, girls, elderly women and nuns by rampant Arbanians”, and compares the suffering of Serbs in Kosovo with their suffering in the Independent State of Croatia. Writing about the Albanians, the clerics mostly describe them as rapists, desecrators, and violent people.

In 1985, representatives of the “Serbian resistance movement” from Kosovo hand in a petition to the state organs, which was also written with the help of Anastasije Jevtić and Dobrica Ćosić, in which they claim that the province is being ruled by “Greater Albanian chauvinists” who have “occupied a part of Yugoslavia” and are committing genocide against Serbs. The Yugoslav authorities didn’t see these accusations as benevolent, but as the inflaming of Serbian nationalism. Serbs held protests around various towns in these years, but on February 26th, 1986, 100 of them went to the federal assembly, demanding the proclamation of the state of emergency in Kosovo and the abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy.

In 1986, the influential SANU[3] Memorandum is published, which describes the demonstrations of the Albanian students as “neofascist aggression” and claims that there is a “physical, political, legal and cultural genocide against the Serbian population” being carried out in Kosovo. No one except the Serbian authors called the problems genocide. The SANU Memorandum was later described by a professional commission of the UN as “a method of spreading anti-Albanian sentiment”. According to the findings of the Human Rights Watch, Serbian media in the 1980s were deliberately spreading disinformation about the wrongdoings against Serbs in Kosovo, including regarding rapes of Serbian women, and were leading a campaign of hatred with the goal of spreading a negative portrayal of Albanians.

The rise of Milošević and the abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy

“The situation in Kosovo, which is not being improved as quickly as desired and promised, is creating a dangerous atmosphere where anything that is said against Serbian nationalism is understood as nationalism. Passionate things can only bring flames.” – Dragiša Pavlović

In April 1987 Serbs organized a meeting in Kosovo Polje against “anti-Serb discrimination” carried out by the Albanian-majority leadership of the province. On this wave of ethnic conflict, Slobodan Milošević rose to the top, expressing support for the Kosovo Serbs during a pre-planned conflict with the province police (“No one should dare beat you!”), winning both the sympathies of the Church as well as nationalist circles of Serbia. Seeing where the wind is blowing, Milošević switched his communist rhetoric for a national one. Thanks to the problem of the Kosovar Serbs, Milošević shortly takes over control in Serbia, eliminating the more moderate competition, Dragiša Pavlović and Ivan Stambolić from the League of Communists of Serbia.

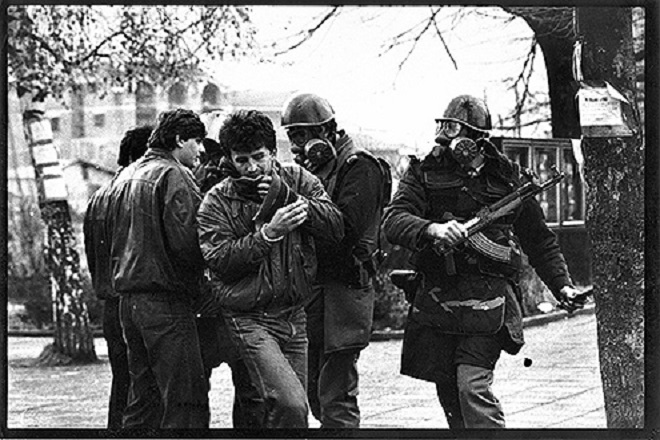

After connecting to the movement of the Kosovar Serbs, Milošević uses them as a political protest force for his “anti-bureaucratic revolutions” with which he carried out a certain sort of annexation of provinces and centralized his power. In the beginning of 1989, Milošević violently abolished Kosovo’s autonomy. The Yugoslav People’s Army established martial law, while police units suppressed the general strike of Kosovar miners who opposed the abolition of autonomy. Hundreds of people are arrested and the Kosovar leadership was replaced by force. During the time of voting on amendments, the Kosovar Assembly building was surrounded by tanks. On March 23rd 1989 the Kosovar Parliament in an atmosphere of martial law, and often without a quorum, agreed with the constitutional amendments with which Kosovo lost its autonomy. During the demonstrations that followed on March 28th 1989, according to the information of Human Rights Watch, 24 people were killed by the police.

Milošević’s triumph was confirmed on June 28th 1989 at Gazimestan, on the 600th anniversary of the Kosovo Battle. In his speech, Milošević called Kosovo the heart of Serbia which later became a widely used political rhetoric. There, in front of 300,000 gathered people he claimed that “armed battles are not out of the question yet” which is today often interpreted as a pronouncement of the Yugoslav Wars: “Again, we are before battles and in battles. These are not armed, but that is not to say that armed battles are out of the question.”

Milošević’s speech marked the end of the Yugoslav idea, and he turned from the communist leader of Serbia into the national leader of Serbs. After Milošević’s Gazemistan triumph, Rugova (1989) uttered just about prophetic words: “Gazemistan is a chauvinistic manifestation. Not only the Serbs fought against the Turks, but Albanians, and Croats, and Bosnians also took part in the battle. This is an event of all Yugoslav nations. My impression is that there are certain powers which want terrorist actions in Kosovo. I can only warn Serbs that whenever a small nation, and Serbs are a small nation, wanted to achieve domination in the Balkans, this always ended with that nation’s tragedy.”

Passive resistance and the development of parallel institutions

As a response to the counter-constitutional abolition of autonomy, on July 2nd, 1990, the Kosovar parliament passed a Constitutional declaration with which Kosovo declared itself a republic, equal to the other Yugoslav republics. Serbia reacted to this by abolishing the Kosovo parliament on July 5th, and replacing the editors of the main Albanian media in Kosovo. Financing for Kosovar institutions was cut, among others the Academy of Science and Arts (in July 1992). Kosovar Albanians began building parallel institutions. On September 7th the MPs of the abolished Assembly met in Kačanik in secret and created a new Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo. A shadow government and an Assembly were chosen. In September 1991 Kosovar Albanians also held an unofficial referendum on independence. On the basis of the referendum, the unrecognized Republic of Kosovo declared itself independent from Yugoslavia. In reality, it didn’t function as an independent state but as a parallel system of government. Throughout the whole of the Milošević period, the institutions of the Republic of Serbia called “Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija” and the institutions of the Kosovar Albanians called “Republic of Kosovo” functioned in parallel.

In the 1990s, Kosovo became a police state under the administration of Belgrade. After the Belgrade authorities took over the provincial authorities, hundreds of thousands of Albanians were fired from state institutions and state companies. Milošević’s authorities closed down the majority of Albanian-language schools and quit paying salaries to Albanian high school teachers. The internationalization of the Kosovo question appeared. Kosovar Albanians started to build their own parallel institutions such as education, health care and others. Albanian pupils and students spent their times in private homes, empty companies, and abandoned school buildings. Milošević’s government wouldn’t allow the development of parallel institutions in Kosovo, and the Serbian police constantly raided the educational and other institutions of Kosovar Albanians. Members of the security forces routinely harassed and beat the teachers, students and managers of the Albanian schools. The police constantly broke basic human rights, and arbitrary arrests and torture became regular occurrences. Kosovar Albanian suffered the terror of Slobodan Milošević more than all the other citizens of Serbia.

The leader of the Kosovar Albanians, Ibrahim Rugova, was known for his support of a nonviolent opposition to Milošević’s regime, as a result of which he is called the “Balkan Gandhi”. During 1991 and 1995, when war was raging in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, the mostly Albanian population of Kosovo supported a passive resistance, refusing to take part in the political structures of Serbia, boycotting elections and censuses. During the times of armed conflicts, Rugova’s Democratic Union of Kosovo refused the offers of the Croatian and Bosnian leadership to open up one more war front against Serbia.

Up to 1995, Rugova’s strategy of non-violent resistance had the wide support of the Albanian population. But after the end of the wars in Croatia and Bosnia, a nonviolent strategy was brought into question, and the number of those Albanians who supported armed resistance was increasing.

The Kosovo War and the eviction of population

In 1996, the thus-far unknown Kosovo Liberation Army started committing terrorist acts against the Serbian authorities in Kosovo and their Albanian associates. The attack on the Serbian police and civilians continued in 1997. The KLA criticized the “passive” approach of the leaders of the Kosovar Albanians, promising to fight for the liberation of Kosovo from Serbian rule. In the end of 1997, Kosovar Albanians declared the region of Drenica “liberated territory” due to the strong presence of KLA forces.

During the 1998, the KLA became stronger and started to engage in guerilla warfare against the Serbian security forces. In the regions of the conflict, the Serbian police and security forces non-selectively and cruelly acted against the civilian population. On March 5th 1998, the special police units, during the chase after KLA leader Adem Jashari, in the village Donji Prekaz, leveled the house of the Jashari family, killing 20 fighters, several elderly men, 18 women and 10 children younger than 16 years. The massacre in Prekaz and other non-selective killings committed in those days in the Drenica area radicalized the Kosovar Albanians and strengthened the KLA which grew into a mass armed resistance movement against the Belgrade government. Many of those who had until then supported Rugova’s policy of non-violence decided for armed resistance.

The battles between the Serbian special police units and the KLA which had under its control a significant part of Kosovo were transformed into the Kosovo War in the middle of 1998. From August 1998 onwards, the Serbian security units started a massive campaign against the KLA. During these conflicts the Yugoslav Army and the Serbian police used “excessive force” (according to the International Crime Court), which resulted in the destruction of villages, relocation of population and death of civilians. The excessive use of state violence, massacres against civilians and the ethnic cleansing committed by the Serbian forces were the motive for NATO bombardment of Serbia in March 1999. In essence, Milošević had no choice but to either hand over or not hand over Kosovo to its inhabitants.

Milošević chose to change the population of Kosovo. After NATO had started the bombing, Milošević engaged all available forces in order to drive out Kosovar Albanians. During the NATO strikes, from March 24th to June 10th, the Serbian police, military and paramilitary began an “all-encompassing campaign of violence” (ICC) against the Albanian population of Kosovo, carrying out forced relocation and massive persecution on an ethnic basis, committing mass murders, pillages, rapes, destruction of religious objects, and whole settlements. Serbian police tried to conceal the killings of Kosovar Albanians by carrying the corpses into Central Serbia, where they were thrown into the Danube or buried in mass graves. During this brutal action of ethnic cleansing 862,979 registered Albanian refugees left Kosovo in a short period of time (data from UNHCR). While they were driving them out, the authorities also illegally took away the IDs from these citizens and destroyed them, carrying out a systematic deletion of identity.

“Results of the action: The last big groups have been broken. Around 2,000 liquidated, many more than in the previous operation. 900,000 have left the land. 1,000 terrorists remain, 300,000 civilians remain.” – War Journal of the general Obrad Stevanović.

Despite the seeming “final solution” of the Kosovo problem, Serbia was forced to withdraw from Kosovo after 78 days of NATO bombardment. In those days, the Albanians returned to Kosovo, and about 100,000 Serbs left the area. Many Serbs who remained were attacked by the furious Albanians who returned while their possessions were destroyed and pillaged. In the following years the number of Serbs and other non-Albanians who moved from Kosovo was about 200,000. Those who remained became easy prey for the KLA which carried out kidnapping and killings of Serbian civilians, and one of the vilest crimes they are accused of (still without a legal epilogue) is the killing of people for organ theft, and sale of it on the black market.

The UN Administration and the declaration of independence

“Had Serbia been smarter, it would have agreed to the demand for Kosovo Republic in 1981 already. Had Serbia done that, perhaps there would be today a democratic and confederal Yugoslaviam state in which all Serbs would live.” – Slovenian political scientist Anton Bebler

After the end of the bombing, Serbia lost control of Kosovo. According to Resolution 1244, Kosovo remained part of FR Yugoslavia, but under control of the United Nations, meaning the KFOR forces. The Serbian minority in Kosovo turned from a privileged minority into a dispossessed minority. In March 2004, violent riots broke out during which Albanian demonstrators attacked Serbian communities in Kosovo. In two days of ethnic conflicts, 19 civilians were killed (11 Albanians and 8 Serbs), hundreds of Serbian homes destroyed and around 35 Orthodox churches. More than 4,000 were driven out, during which certain settlements were left with no Serbs at all.

In February 2006 negotiations began on the status of Kosovo. The international arbitrator, the Finnish politician Marti Ahtisaari recommended the plan of “controlled independence” which the Serbian side rejected, but the Albanian accepted. Serbia suggested that the status of Kosovo be regulated similarly to that of Hong Kong in China or the Oeland in Finland, but the Kosovar Albanians rejected any proposition that would put Kosovo inside Serbia.

In a deal with Western powers, the Assembly of Kosovo on February 17th 2008 unilaterally declared independence of Kosovo, with all 109 present MPs, while 11 Serbian MPs boycotted the vote. This decision was in the same night declared illegal by the Government of Serbia, and from then on Serbian diplomacy has worked intensely against Kosovar independence.

Whether Serbia likes it or not, the majority of European states today recognize Kosovo as the youngest European state. Kosovar institutions control most of Kosovo, except for the north which is under the control of Serbs. While I am writing this (2011), there are barricades on the north of Kosovo; Belgrade and Prishtina still cannot reach any sort of deal.

Summary

After due to the Balkan Wars Kosovo became part of Serbia for a short period of time, the First World War broke out. After World War I, Kosovo became part of Yugoslavia, its permanent problem, and one of the major reasons of its break-up.

The Yugoslav period of the Kosovar history was, unfortunately, rather violent. During the majority of the Yugoslav period, Kosovo either had a state of emergency or martial law. Everything taken into account, there was the least violence in the period of the development of Kosovar autonomy, from the removal of Ranković in 1966 to the 1981 riots. And even the period of the genocide propaganda in the 1980s seems relatively mild compared to what happened later when the mass killing really began.

The main demographic tendencies in the Yugoslav period were the planned migrations of the Serbs in the period of the Kingdom, and the chaotic movements in the period of SFRY. There are a lot less Serbs today in Kosovo statistically than 100 years ago. As a majority, Serbs now only exist in the North of Kosovo where they were also the majority in the beginning of the century. They even became the minority in the towns that were founded by colonization like Obilić and Kosovo Polje. From many towns, they have completely been driven out.

How to proceed?

As we have seen, the problems with Kosovo didn’t come into existence today or yesterday, they have existed since Kosovo entered Serbian/Yugoslav state. Many Serbs with whom I have talked to would love for the problem to be solved by all the Albanians there disappearing. I think that is not realistic, and most importantly, not humane.

Is the solution another conquest of Kosovo? That has been done for too many times already (1912, 1918, 1944, 1989, 1999), but we simply didn’t know what to do with it. Belgrade has tried all the violent methods in the 20th century: gradual relocation, expulsions, martial law, colonization, etc… It was because of these policies, that Kosovar Serbs always suffered. As if by a rule, every instance of Belgrade violence caused a worsening of the situation and the migration of the Kosovar Serbs.

Literature:

Izveštaj međunarodne komisije o balkanskim ratovima, Vašington, 1914.

Dimitrije Tucović, Srbija i Albanija, Beograd, 1914.

Dimitrije Bogdanović, Knjiga o Kosovu, Beograd, 1985.

Isterivanja Albanaca i kolonizacija Kosova, Istorijski institut u Prištini, 1997.

Noel Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History, Macmilan, London, 1998.

Kosovo: kako viđeno, tako rečeno (Izveštaj OEBS-a), 1999.

Po naređenju: ratni zločini na Kosovu (Izveštaj Human Rights Watch-a), 2001.

Aleksandar Pavlović, Prostorni raspored Srba i Crnogoraca kolonizovanih na Kosovo i Metohiju u periodu između 1918. i 1941. godine, Baština br. 24, 2008.

Transkripti sa suđenja Miloševiću, Fond za humanitarno pravo, 2009.

Presuda Miloševićevim saradnicima za zločine na Kosovu, MKSJ, 2009.

[1] The Balli Kombëtar (literally National Front), known as Balli, was an Albanian nationalist anti-communist resistance movement and a political organization established in November 1942. It was led by Ali Këlcyra and Midhat Frashëri and was formed by members from the landowning elite, liberal nationalists opposed to communism and other sectors of society in Albania.The motto of the Balli Kombëtar was: “Shqipëria Shqiptarëve, Vdekje Tradhëtarëve” (Albania for the Albanians, Death to the Traitors). Eventually the Balli Kombëtar joined the Nazi established puppet government and fought as an ally against anti-fascist guerrilla groups.

[2] The Kosovo Myth, or the Kosovo Cult (Serbian: Косовски Завет / Kosovski Zavet) is a belief asserting that the Battle of Kosovo (June 1389) symbolizes a martyrdom of the Serbian nation in defense of their honor and Christendom against Turks (non-believers). The essence of the myth is that during the battle, Serbs, headed by Prince Lazar, lost because they consciously sacrificed the earthly kingdom in order to gain the Kingdom of Heaven. Since the 19th century Kosovo Myth became an important constitutive element of nationalist identity, as well as cultural and political homogenization of Serbs. The basic elements of the Kosovo Myth are vengeance, martyrdom, betrayal and glory.

[3] Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Serbian: Српска академија наука и уметности/Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, abbr. САНУ/SANU)