Marijana Stojčić

Proletarians of the world – who washes your socks? From female Partisans to Comrade Woman[*]

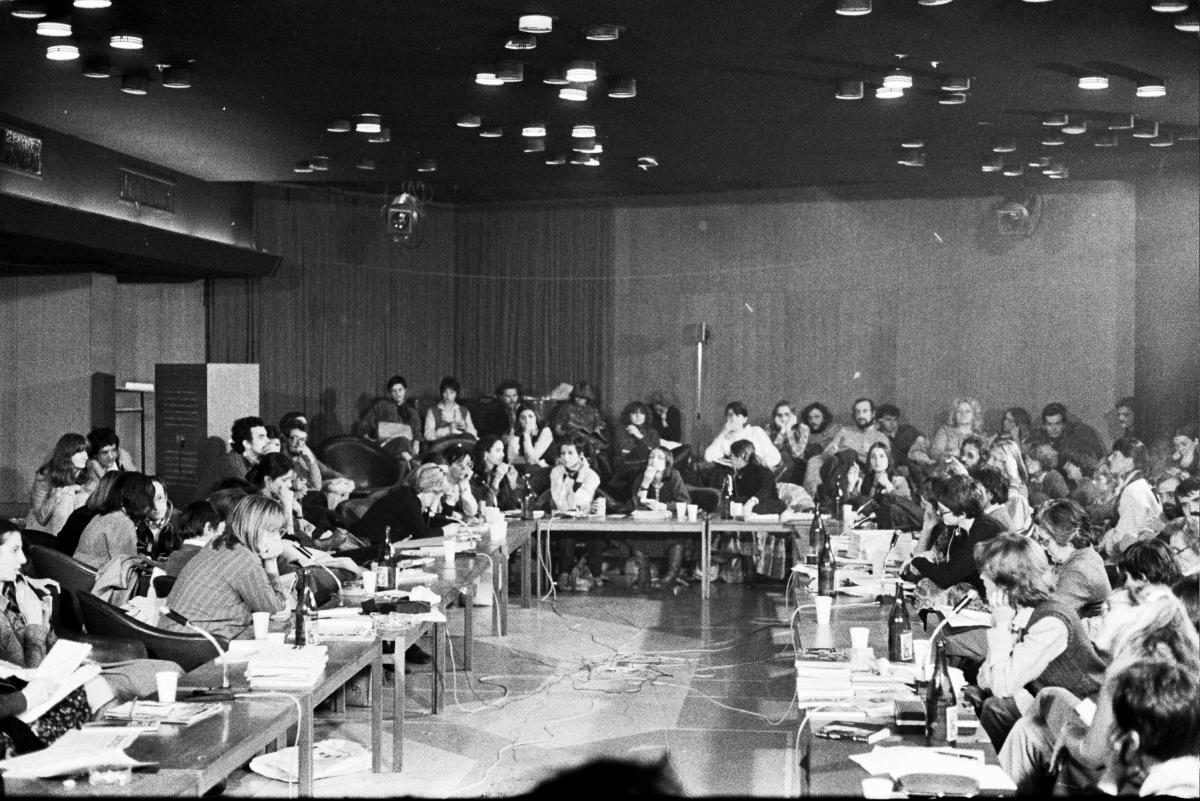

A key milestone in the development of feminist movements in former Yugoslavia was the international conference “Comrade Woman: The Women’s Question. New Approach?” in the Student Cultural Centre (SKC) in Belgrade in 1978, organized by women from Belgrade, Zagreb, Sarajevo and Ljubljana. This was the first feminist event of the second wave of feminism in Eastern Europe.

The impact of second wave feminism in the 1970s in the space which we now call former Yugoslavia coincides, on the one hand, with a serious crisis of political legitimation of the Yugoslav socialist project and the constitution of a specific group which in basic class terms we can locate as a new middle-class[1]. On the other hand, at the height of the welfare state in the West, the crisis of the old left and the workers’ movement in the classical sense, as well as the rise of new social movements gathered around a critique of the statism, authoritarianism and paternalism of the welfare state, led to demands for more flexible social relations, freedom of life-styles, and personal self-realisation. In general terms, one can easily discuss whether the new social movements introduced new forms of politics, or whether the change was more subtle, in terms of orientation, organization, and activities[2], in the new social context in which the movements found themselves, considering “the ever decreasing extent of explicit class-based identification, the lack of support of political parties organized to represent class interests, and the politicization of identities such as gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and nationality previously marginalized in conventional politics[3]”. The success of welfare states in the West had already become normalized, with that model judged successful in terms of the provision of material goods and social security, together with a significantly higher level of political freedom in comparison with the countries of real-socialism. The old left had identified itself with wide-ranging economic demands which had more or less been achieved or were on the road to being achieved. The framework of class struggle had seemed to be too limited in terms of a critique of the inequalities, lack of freedoms, and exclusions which still persisted. To the forefront came other forms of societal repression – primarily gender and race which, historically, workers’ movements had routinely relegated to second place.

Although in the space which today we term former Yugoslavia, a tradition of women’s organizing existed already in the 19th century, but from the (self-)abolition of the Anti-Fascist Women’s Front (AFŽ) in 1953 to the conference “Drug-ca Žena”, the women’s question completely disappeared from the public sphere. The position of women in 19th century Serbia, as well as in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the first half of the 20th century, did not differ significantly from the position of women elsewhere in the world nor in terms of the problems that they wished to see resolved.[4] Historically, the women’s movement also developed in the Yugoslav space through women’s societies whose main activities in the beginning were linked primarily to humanitarian work and aid to the poor, particularly to women and children. For many middle- and upper-class women it was precisely advocacy for the poor and oppressed which constituted the first phase of their engagement in favour of their own kind. Insofar as any of these organizations contained some feminist ideas, these remained secondary or were neglected completely. In Austro-Hungaria from the second half of the 19th century, many women’s societies were active, initially organized on a national or a confessional basis. The creation of an organization within the frame of one nationality often led to the formation of the same or similar organisations by other nationalities. It is important to emphasise that one can find a significant number of ecumenical actions in virtually all women’s humanitarian organisations. Moreover, amongst the membership of a single national humanitarian organisation, one can find members of other nationalities. Until World War I across the whole of Yugoslavia, there was a wide network of women’s humanitarian organisations co-operating with each other.[5]

After World War I a new state was created in the Balkans – the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (which became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). The position of women varied greatly according to nationality and religion. Legal regulations also differed greatly. Until the start of World War II, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia found itself in the group of underdeveloped capitalist countries with high dependence on an agrarian economic structure: in 1931, 76% of all economically active persons worked primarily in agriculture, forestry and fishing, and only 11% in industrial and craft activities[6]. Based on the same census, 44.6% of the population was illiterate, including 56.4% of women over 10 years old compared to 32% of men.[7] The majority of women lived in villages where heavy physical work was combined with reproductive labour and exposure to various forms of violence.[8] Although the situation of women varied greatly based on nationality and religion, as well as on the country where they lived prior to the formation of the new state, all women shared the experience of dramatic gender-based legal and social inequalities.[9] In the words of Jelena Petrović, economic and political inequality was reflected in: „Differential political and civic rights (the right to vote, ownership, inheritance and so on), a very limited choice of professions (teachers, lower grade civil servants – typists, telephonists, cashiers, available to a small number of women, or else textile workers, workers in the tobacco industry, and of course, maids), exploitation (significantly lower pay than men in the same jobs, in the worst jobs, at the same time performing all housework, and in villages undertaking hard seasonal work), private ownership of women (by their fathers, and subsequently husbands, especially in rural areas in which, according to the 1931 census, 76% of the population lived), the cultural exclusion of women and their exclusion from public life (with rare exceptions, ‘femininity’ was tolerated in the public sphere as a kind of innate handicap), and so on.“[10] Nevertheless, between the two World Wars, a large number of women’s associations and journals were working, diverging ideologically, from socialist to clerico-fascist, functioning more or less legally according to changes in the wider political situation.[11] Generally, between the two World Wars, one can distinguish women’s organisations in terms of two broad currents – those in the framework of the workers’ movement and those which were a separate civic movement. On a number of occasions (such as in the collective action campaigning for the right to vote in 1935), joint activities eroded ideological differences. On the initiative of the Serbian National Women’s Federation (Srpskog naroda ženski savez) founded in 1906, at their first Congress in Belgrade in 1919, a NATIONAL WOMEN’S FEDERATION OF SERBS, CROATS AND SLOVENES (NARODNI ŽENSKI SAVEZ SRPKINJA, HRVATICA I SLOVENKI) was formed. The Federation gathered together all national, educational and humanitarian societies, around 200 in total, on a single wide platform which implied work on the development of humane, ethical, cultural and feminist basis – both social and national in character. The Federation joined the International Council of Women (ICW), actively participating in its work and adapting to the international feminist standards of the day, advocating for women’s education, the right to vote, and equality between women and men in all aspects of social life. Later, the Federation became the Yugoslav Women’s Federation (Jugoslovenski ženski savez).

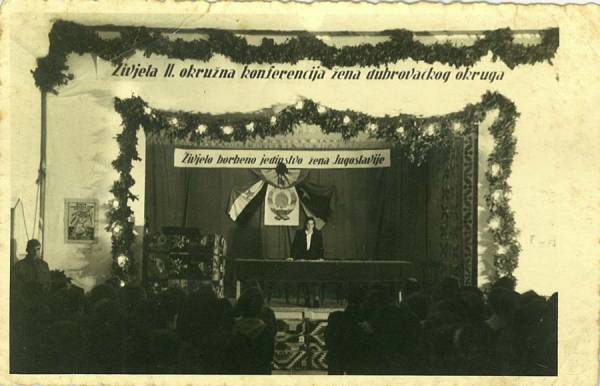

With the start of World War II, women’s organisations stopped working, but a significant number of women were actively included in the fight to liberate the country through participation in armed actions and in the background.[12] From the networks of women’s organisations which formed in all of the liberated territories and in some of the unliberated ones, emerged the Anti-Fascist Women’s Front (Antifašistički front žena AFŽ) in 1942. The first AFŽ conference was held from 5 to 7 December 1942 in Bosanski Petrovac, attended by Josip Broz Tito, which was of great symbolic value. The conference has been considered as an historic milestone in the struggle for women’s equality and pointed to the contribution of women in the liberation struggle: “90% of everything that our army does today can be credited to our heroic Yugoslav women». In addition, the aims of AFŽ did not stop with victory over the occupier but also focused on the struggle to finally realise women’s emancipation.[13] Considering the role of the AFŽ, Lydia Sklevicky suggested that it had two main sets of inter-related tasks. The first concerned the national liberation movement in general, including support to the military (collecting food, material goods, voluntary work, and so on), and organizing life in the background and ensuring normal life in the liberated territories, including the implementation of all aspects of social policy (care of the wounded, children, and those unable to support themselves). The second set of tasks for the AFŽ related to the political and cultural emancipation of women and their inclusion on an equal basis in the National Liberation Struggle (NOB) and in the building of a post-war society.[14] Already at the Fifth Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) in 1940, when two women were elected to the Central Committee, Spasenija Babović and Vida Tomšič, both future Presidents of AFŽ, the resolution which Tošić developed in her speech was adopted, namely that “all party organisations devote most attention to work among women”, and that these efforts should actively involve men as well.[15] These were joined by hitherto unrealized demands of earlier women’s, civil and workers’ movements in the programme of the Communist Party: “for the protection of maternity, for the elimination of dual morality in public and private life, for economic equality and for the recognition of the right to vote„[16]. The education of women was a particularly important precondition for achieving equality. As Sklevycki stated: “The AFŽ devoted a large part of its activities in that direction, and we can distinguish between a number of levels on which this task was accomplished. At an elementary level, it encompassed literacy courses and general education as a supplement to political education –including writing in the women’s press and promoting it being read was, in fact, an invitation for the creation of a new, activist, identity”.[17] The AFŽ Press played an important role in all of this. As Gordana Stojaković has suggested, in the period between 1942 and 1945 in the parts of Yugoslavia where the national liberation movement existed, some 30 periodicals were published aimed at women, and within the framework of AFŽ and the KPJ.[18] It can be stated that the Anti-Fascist Women’s Front was the channel through which women articulated their demands for equality with men in all aspects of society. For a majority of women, participation in resistance to fascism and the liberation movement, together with participation in the “organs of national government” which were elected during the war, marked the beginnings of their politicization and constitution as a political subject.

After the war, along with numerous tasks which the AFŽ set itself in terms of the building and reconstruction of the country, at the centre of its attention was the endeavour to ensure that the entire post-war legal system was based on the principle of women’s equality and against attempts to maintain gender discrimination. Yugoslav women participated for the first time in elections for the Constitutional Assembly in 1945. A large percentage of women participated in those elections, confirmed by data presented at the Third AFŽ Congress, which suggested that the female participation rate was 88%.[19] The 1946 Constitution confirmed women’s equality in all spheres of societal life. The Constitution merely confirmed, or rather raised to the level of Constitutional Law, the rights of women that had already been acquired. In this case, the Constitution did not bring about the practice of equal electoral rights between men and women, but rather these principles arose from this practice.

In all laws which were subsequently adopted, this principle was strictly adhered to. The principle of equality, promoted as one of the central principles planned by the new state, reflected the radical revolutionary position in relation to class, gender and national inequality. As well as education, women’s economic independence was seen as a prerequisite for women’s emancipation. Women and men were equal, more than anything, as members of the working class. As Gordana Stojaković quotes: ”the socialist ideology of emancipation of women was not looked at outside of the system of workerism (the working class) because measures of women’s emancipation, above all, were developed in relation to labour rights.”[20] Immediately after the war, with the need to speed up the modernization of the country, negative attitudes about the inferiority of women were treated not only as indicators of social, but also political, backwardness. In this way, the question of inequality between men and women was posed as a social and political question which, if left unresolved, would render the transformation of society in a new revolutionary direction impossible. At the same time, in this period through the AFŽ, the so-called ‘women’s question’, however insecure and partial it seemed, gained an independent status, where women became agents in their own emancipation and, at the same time, active subjects in the building of a new socialist society.

Here one has to bear in mind that the idea of the economic independence of women, as a fundamental precondition for her emancipation on the basis of socialist emancipatory ideology, was understood primarily in terms of the realization of the rights of women in the workplace. After the war, this did not derive only from the ideology of the authorities, but also from the necessity of engaging as many people as possible in the post-war reconstruction of a country in ruins, and later in terms of the ambitious demands of the five-year plan. It was from this imperative for both the state and the AFŽ that as many women as possible be employed and included in different forms of agricultural activities, as well as in those activities which in pre-war Yugoslavia had employed exclusively or primarily men. The period immediately after the war was one of intensive social reconstruction and of struggle for the meaning of the new social (and gender) order, in which war heroism was replaced by worker’s heroism. It was necessary to both stabilize socialism and rebuild a destroyed country. Some 400,000 people remained homeless, and war damages amounted to some 2.3 billion US dollars. The first period looked at from an economic perspective in the period of centralized administrative management (1945–1952), marked by a complex system of austerity measures (coupons for rationing consumption) and of production (The First Five-Year Plan, 1947–1951). Immediately after the war, the UN and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) donated to Yugoslavia goods (mainly food) worth approximately 416m. USD.[21] In the first decade of the post-war reconstruction of society women had reserved workplaces as female workers – shock workers, and women were meant to participate at the same level as men in collective actions. On the one hand, poverty and rationing were additional motivations for women to compete for the status of shock worker in order to ensure additional coupons for food, clothing and textiles[22]; on the other hand, the intensive agitation of the AFŽ primarily through the press worked on the construction of women-workers as crucial protagonists in the successful realization of the socialist project. The struggle was not framed only as a struggle for emancipation but also as a struggle to realise the formidable five-year plan (from 1947 to 1951). Women were mobilized on many levels: activated through labour actions, attending literacy classes, as well as sewing classes, as workers and shock workers, while, in parallel it was expected of them that they would continue to care for the household. State policy used the figure of the New Woman as the symbolic carrier of modernization[23], and women’s visibility in the socio-cultural sphere of the new state was meant to mark the progress made in the new realities. As Ksenija Vidmar-Horvat suggested, to understand the complex socialist gender politics and its definition of women’s role in socialism, it is important to pay attention to three underlying fields: the sphere of work, marital and family life and relations with children, with the socialist project invoking radical change in all three fields comparted to the bourgeois subjugation of women.[24]

Socialist democracy in the Yugoslav case was primarily understood as economic democracy based on national equality and social equality. A personal contribution to the country’s construction, the ability to manage the production process, and thus the process of social modernization, meant that one became an agent, an autonomous subject of one’s own progress. The worker had a central role in the construction of “the cosmopolitan, internationalist, modern and supranational identity of a Yugoslav citizen in the period of socialism”[25]. When it came to the question of women, socialist ideology did not regard the emancipation of women outside of the workerist system (the working class). As Ksenija Vidmar Horvat has pointed out, as “female comrades” (“drugarice”) women were an integral part of the proletariat who were not considered for any additional special rights separable from the rights they enjoyed and demands they formulated as part of the working class. Gender discourse in the SFRY mainly focused on the role of women in nationalised industries, with the traditional model being largely retained in aspects of private family life (marriage, motherhood, gender roles). Within the socialist model there were attempts to harmonize and integrate functions of a worker with those functions which women carried out in the private sphere with a particular accent on motherhood. Although the state introduced measures which were meant to facilitate the connections between the public (the sphere of work and political engagement) and the private (primarily in terms of motherhood such as paid maternity leave, practically free kindergartens, a hot meal for children in schools, and so on[26]), the standpoint that women as a social group were indistinguishable from men prevailed.[27] The “self-abolition” of the Anti-fascist Women’s Front in 1953[28] marked the abolition of the autonomy of the so-called women’s question, and was a step backwards in terms of returning women to the household sphere, resulting in the political pacification of a large number of women[29] and the end of the intense interest in changing gender relations in the family and society. Henceforth, the women’s question would be treated as an integral part of the class question, which is then presented as the key social question on which everyone should focus. Simplified somewhat, starting with the view that the basis of social injustice lies in unequal economic distribution (the typical example of which is class inequality), the resolution of the class question is meant to lead to the simultaneous solution of “the women’s question”. Formulated slightly differently: “Starting from the Marxist position that the emancipation of women can only be achieved through the realization of ‘associations of free labour’, the women’s question became an integral part of the class question”. As the class question was felt to have been resolved in Yugoslavia, it followed that it could be asserted that “women today are formally equal in our society”.[30]

The period from 1950 to 1970 was a period of economic prosperity and an increasing standard of living in the SFRY; and from the 1960s of open borders and an overall liberalization of society, with a constant increase in the number of women included in the labour market.[31] As stated earlier, paid work and education of women (regulated by very advanced legal provisions) were seen as the most important factors in the emancipation of women.[32] Yugoslav women first participated in elections for the Constitutional Council in 1945. The 1946 Constitution confirmed women’s equality in all aspects of social life.[33] In all laws which were passed later this principle was strictly respected. According to the Marriage Law [1946], the position of women and men in marriage was equalised, the Family Law of 1947 equalised the rights of children born in and out of wedlock, the Law on Social Insurance introduced social protection against all risks, including paid maternity leave and the right to old age pension under the same conditions for men and women, even though women tended to retire earlier. The right to abortion was secured in a 1951 law. The 1974 Constitution guaranteed the right to give birth for free, and from 1977 abortion was permitted with no restrictions up to ten weeks of pregnancy. Yugoslavia in those days had legislation which was in accordance with all international conventions which pertained to the position of women.

At the same time, there were significant differences in the level of development of the Yugoslav republics, in terms of opportunities and quality of life, between the developed and underdeveloped republics, and between rural and urban parts of the country. After the 1974 Constitution, there emerged different legal provisions around particular issues in different Yugoslav republics. Despite progressive legal provisions and proclamations about the equal status of men and women, the realities of everyday life were different.[34] The mass involvement of women in the economy of socialist Yugoslavia gave rise to a new situation in which women were active in regular work, as socio-political workers, and at home. On the other hand, the social and political engagement of women began to reduce in the 1950s. Even then, an AFŽ activist noted the rise in attitudes such as “now that we have built socialism women can return to the home and bring up the children“[35], and a weakening of the ideological enthusiasm to challenge patriarchal understandings, earlier sharply condemned as backward and counterrevolutionary[36]. According to Stojaković, some of the reasons can be found in the fact that there was no longer a need for a large engaged workforce. In addition, with the introduction of self-management, pressure on enterprises to show positive results led to a reduction in subsidies for social protection institutions (kindergartens and nurseries) and the dismissal of lower qualified workers (a group still dominated by women).[37] Furthermore, mass migration into the cities was not accompanied by adequate measures to ensure that women from rural households could become more employable in city surroundings[38], leaving them structurally outside of the public sphere, and without the possibility of achieving economic independence and relief from the burdens of childcare. Once the already achieved socialised care of children and mothers[39] became too expensive, leaving paid work was, for part of the female population, also a way out of the dual burden of responsibilities – in the work place and at home. Although some attempts were made to open household services for women, very few were able to take advantage of this.[40] A similar situation arose when restaurants serving communal food were opened; their users were predominantly single men.[41] In a survey carried out in June 1956 by the magazine “Praktična žena” (Practical Woman), one of the women surveyed wrote this: “You say that my working day lasts 13 hours. Thanks a lot! For me it lasts almost 18 hours. Am I exaggerating? I would love you to be in my place… First, I am on my feet for 8 hours, working hard. And then cooking, washing, cleaning and so on. Double working time, four times going to work and back. And my husband will not even bring his clothes to be washed, nor go to the market when he has time». Another account is, also, highly illustrative: «I often hear a customer at the counter … Four years I have not been to a Trades’ Union meeting … I am still at the level I was (if not lower) when my first child was born». For many, the solution was the return of women to the home as the place where they ‘naturally’ belonged. Or in the words of another woman surveyed: „Now it’s like this: if you want to be good at your work you have to abandon your family; if you run the house well then you don’t perform well at work. It’s better then that you completely return to the family. Or that men take over those responsibilities. And we are really not for that. Do not misunderstand me! I am not in favour of this, it’s just that that’s how it is for me. Women protest but I doubt that that they will get any help.“ [42] Mitra Mitrović, amongst other things, a pre-war communist and one of the influential members of the AFŽ until it was abolished, wrote bitterly about all this: „And maybe there is no question – all at once a huge gap has emerged: from full civilization to full discrimination. There is nothing unusual about this. It is like moving from complete riches to complete poverty, or from a fully developed country to complete backwardness. But it seems that here, regarding this problematic, even more than race or class, the enslavement is more abominable, more complicated, because it does not just depend on the powerful, it does not only concern foreign or faraway lands, the rich or the white people, but those closest to us, individual people, fathers and brothers, even sons, who cannot escape from the perceptions and prejudices imposed upon them, that have become an integral part of life, customs and household order“.[43] Already in the 1950s in the press it is possible to detect a different trend than that which was prevalent during the war and initial post-war years. While the themes in magazines during and after the war mainly concentrated on the national liberation struggle, and the political situation, it also explored the new role and equal status of women, firstly in war, and subsequently in the reconstruction of the country, and from the 1950s a cult of femininity and beauty, haute couture and fashion news, dropped after the war, were again revived. Domestic illustrated and fashion magazines began to be published carrying fashion news and photographs, imitating Western examples.[44] Daily newspapers gradually developed their women’s sections, namely female-oriented content primarily offering tips for running the household, hygiene, and fashion and make-up. The presentation of women as subjects, young and old, from urban and rural areas, educated and literate who, through personal dedication, can do things for themselves in terms of women’s rights and the public good (whether in active women’s roles or in the economy of care) which dominated after the war, was gradually replaced by a reaffirmation of traditional female gender stereotypes. The staple themes of the women’s press at the end of the 1950s, included home as the centre of well-being and the body as a symbol of open sexuality and direct seduction.[45]

It is important to note that this process of reaffirming traditional gender stereotypes occurred gradually and never unambiguously. It was marked by numerous contradictions and oscillations between efforts for women’s emancipation and the perpetuation of gender essentialism, illustrative of the ambivalence of Yugoslav socialism in terms of the position of women. The circumstances of entry into World War II, and after that participation in the development and reconstruction of the country had offered, for a majority of women, a road towards politicization and political subjectivity. Their participation was a necessary condition for this to happen. The official position throughout Yugoslav socialism was that women’s right to work and to participation in political life was an indisputable fact of war and revolution. It is important to bear in mind that the Partisan struggle for liberation from Nazi occupation was one of the basic myths, promoted through films, books, music and official documents. The value of women’s active participation in struggle and work in the background represented an important aspect of socialist rhetoric.

At the same time, women’s dual role, as a worker and mother, as the one primarily responsible for reproduction and the family, was never questioned. This inevitably led to a dual burden for women. It can be said that women’s two roles – as a “socialist worker” in the public sphere (and in official discourse) and Western consumerist ideas of femininity in the private sphere, came to merge together and fuse. The dominant ideology of everyday life became consumerism. The ideal role model for women was one who successfully balanced being a caring mother, a housewife, a partner and an employed woman, without compromising on her beauty, sexual attraction and femininity. On the other hand, there was no longer any meaningful feminist movement, nor any critical problematisation of gender roles in society. Violence against women as an issue was also completely absent from the public sphere.

The presentation of Yugoslav women as “liberated” and “westernized” truly reflected the experience of women in the middle- and upper-class from urban surroundings; the experience of the majority of women and men from rural and semi-urban regions never fitted into this mythological picture of social progress. This gap between the centre and periphery is also crucial to understanding the position of women who organized the conference, as well as the subsequent development of feminist groups and movement in Yugoslavia. The mid-1970s was a time when second-wave feminism entered the Yugoslav space. A generation of young educated women from urban centres, such as Zagreb and Belgrade, formed the nucleus of the new feminist movement of the early 1970s. These women had access to education and employment, but had experienced the difference between the proclaimed equality between men and women and the realities of everyday life: sexism in the private sphere, on the labour market and in terms of academic careers. On their travels to Western Europe and the USA, they became acquainted with feminist movements and feminist theories, and the new feminist movement in Yugoslavia would not have been possible without the turmoil of ’68, as well as the intense intellectual debates on Marxism and alternatives to capitalism and Stalinism in leftist dissident circles (gathered around the journals “Perspektive” and “Praxis” as well as the Korčula summer school), which had been taking place since the early 1960s.[46] This is visible in terms of the student demands from 1968. The student movement articulated its demands within the framework of so-called ideology, pointing to the gap between the proclaimed values and the disappointing reality of socialism.[47]

In Portorož in 1976, the Croatian Sociological Association organised a symposium on the social situation of women and the development of the family in Yugoslav self-managed society which marked the beginnings of contemporary Yugoslav feminism. One of the participants of the symposium was Žarana Papić who later, in 1978, together with Dunja Blažević (then director of SKC) and Jasmina Tešanović, organised in the Student Cultural Centre (SKC) in Belgrade the conference “DRUG-CA ŽENA. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup?” (“Comrade Woman: the women’s question – a new approach”). The Student Cultural Centre was, at that time, despite being state financed, the centre of all alternative cultural events. As Chiara Bonfiglioli has noted, referring to the words of Rada Iveković: “Political dissidents and leftist groups would meet there, but also scientists and artists, foreign and domestic, interested in art, literature, philosophy, everything”.[48] This meeting is considered to be the beginning of the development of the feminist movement in then Yugoslavia. Its significance was a result of bringing together women who, albeit individually and separately, were already concerned with feminist theory across socialist Yugoslavia, as well as feminists from elsewhere in Europe.

The original programme had two parts: a meeting of Yugoslav feminists (from 24 – 26 October), and a second part which is remembered as a crucial moment. The conference was attended by around thirty foreign particpants from the whole of Europe and around twenty particpants from Yugoslavia, mainly from Zagreb and Belgrade. Among them were Helen Cixous, Hatz Garcia, Nil Yalter, and Christine Delphy from France, Jill Lewis, Helen Roberts and Parveen Adams from the UK, Dacia Maraini, Carla Ravaioli and Chiara Saraceno from Italy, Ewa Morawska from Poland, Judith Kele from Hungary, Alice Scwarzer, Nadežda Čačinović-Puhovski, Slavenka Drakulić-Ilić, Đurđa Milanović and Vesna Pusić from Zagreb, Nada Ler-Sofronić from Sarajevo; Silva Mežnarić from Ljubljana and Rada Iveković, Anđelka Milić, Jasmina Tešanović, Lepa Mlađenović and Sonja Drljević from Belgrade. However, many others came to the conference from Yugoslavia and abroad who were uninvited or unannounced. Given that some who were announced failed to attend (or at least their names are missing from the participants’ list), it is relatively difficult to say with certainty how many participants attended, female and male. Chiara Bonfiglioli suggests that overall there were around eighty attendees. She reports on the words of Dragan Klaić which beautifully capture the atmosphere of those days: „I will tell you what for me was very important, as the first conference of its kind, with a feminist agenda, which tried to gather people from Zagreb, from Belgrade, from the whole of Yugoslavia and from abroad. There were around eighty people on those two days. It was an attempt by a feminist core to escape from a very narrow intellectual circle, to attract young people and get some media attention. It was fascinating to bring all those people from abroad, with very different perspectives. It was very dynamic and polemical, albeit slowed down because of translation. From Italian to English, from English to Serbo-Croatian, German, French, Spanish. … I remember eighty people sitting for two days there, socializing in the evenings and questioning each other with the utmost curiosity.”[49]. As well as discussions, part of the programme consisted of exhibitions and film projections by women artists and directors. The themes which were discussed at the conference can be gleaned from the contents of the reader prepared by Žarana Papić. It included marxist and socialist feminist texts (texts by Alexandra Kollontai, Evelyn Reed and Sheila Rowbotham, feminist analyses which combined marxism and psychoanalysis by Shulamit Firestone and Juliet Mitchell, Luce Irigaray’s theory of sexual difference, as well as texts from the feminist movement in Italy by Manuela Fraire and Rosalba Spagnolleti). The texts of domestic authors mainly concentrated on analysing Yugoslav society from a feminist viewpoint, as well as questions regarding the relevance and applicability of feminism in a socialist society. At the conference there were discussions on patriarchy, identity, sexuality, language, the invisibility of women in culture and science, as well as the everyday lives of women, discrimination against women in the public and private spheres, women’s dual burden, violence against women, and on the survival of traditional patriarchal roles despite normative solutions which guaranteed equality. For the first time, a critical review was presented on the resolution of women’s issues in Yugoslavia. The critique was feminist, but not anti-socialist.[50]

Differences in understanding and experience were also revealed between domestic and foreign guests. Domestic participants had academic backgrounds without any experience in practical academic work. This was one of the crucial differences in relation to guests from abroad. In addition, they did not present themselves as a priori against the system, but they drew attention to how that society in reality differed from its proclaimed values. All these differences were visible throughout the conference, particularly in discussions with participants from Western Europe. The experience from ’68 and the vain hope that hierarchical relations between men and women could be abolished through a mass movement[51] made Western guests much more critical not only with regard to the possibility of women’s freedom through ‘formal’ emancipation – liberal emancipation through laws, as well as regarding Marxist theory of the liberation of women through class struggle. The conference, somehow, situated Yugoslavia between the West and its feminist debates, and Eastern Europe where no one had heard of feminism, other than with regard to «ugly lesbians».[52] From a Western feminist perspective, Yugoslav feminists were not radical enough. From the perspective of domestic particpants, guests from the West were in no way adequately informed about the situation in Yugoslavia, and occasionally, were condescending and pretentious. One of the sources of the disagreement was the lack of understanding of foreign particpants that many of the themes which preoccupied the feminist movement in the West (such as divorce or abortion rights) were not on the agenda in Yugoslavia because of the progressive regulatory and legal framework. In addition, at that time there was no feminist movement in Yugoslavia[53], and the women who organised the conference did not represent any kind of „Yugoslav woman“ across the entire territory of Yugoslavia. The position of women in Yugoslavia differed significantly not only in regard to education and the possibility of travelling, but also in terms of which part of Yugoslavia women lived and whether this was an urban milieu or not. One of the other important points of disagreement was the participation of men in the conference. In the Belgrade conference a significant number of men were present. This was problematic for a large part of the Western feminist participants. These, particularly French and Italian feminists, understood the participation of men in the conference as the usurpation of women’s space. In contrast, the majority of local particpants supported the presence of feminist friendly men in the meeting. Dacia Maraini remembers tensions at the end of the first day, when Italian delegates protested against the fact that a male sociologist[54] spoke about repression against women. They were opposed by the organisers, clarifying that both men and women have to fight discrimination, and that they were against any kind of discrimination on the basis of gender differences.[55]

From today’s perspective, one can freely state that „DRUG-CA ŽENA. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup?” made history. Not only did in bring back prohibited themes – feminism in the public sphere – and was the first critical framework for resolving the „woman’s question“ in then socialist Yugoslavia, but primarily because of the impact it had on participants, both female and male[56], and on the later development of feminism and feminist groups. It emboldened participants to believe in themselves and begin to work openly in the public sphere, and, as such, is the foundational event of the entire later development of the feminist movement in this region. The conference was a milestone in the subsequent development of feminist groups. Quickly after the conference Lidija Skelvicky, Rada Iveković and Slavenka Drakulić formed a group Žena i društvo in Zagreb under the auspices of the Croatian Sociological Association. After the return of Sofija Trivunac from Zagreb, a group of the same name was formed in Belgrade in 1980, within the Student Cultural Centre. In contrast to the Zagreb group which mainly focused on theoretical work and whose audience for round tables was mainly academic, the Belgrade group discussed their own experiences and worked on self-empowerment. In round tables at SKC every Wednesday, a different theme was discussed[57]. As Lina Vušković remembers: “The choice of themes was very broad and we did not pursue any particular strategy or sequence except when the questions became too broad. We organized a large number of round tables on sexuality (which were very well attended, especially when a psychoanalytic perspective was included), reproductive rights, the role of Christianity, the position of women at work, rape, aesthetic racism, women’s writing, language and gender, the patriarchal mystification of scientific language, the analysis of Serbian national narratives, an analysis of children’s literature, the impact of children’s toys and games in determining gender roles …”[58] Co-operation with feminists from other parts of the country, especially from Zagreb, was very intense. Rada Iveković, Slavenka Drakulić, Jelena Zupa, Biljana Kašić, Vesna Kesić, Katarina Vidović, Slavica Jakobović, Vesna Pusić and others regularly came to Belgrade. In round tables at SKC for nigh on three years, guests included those who did not exclusively focus on feminism, but whose work was connected to the problematic of women’s emancipation (Vesna Pešić, Nebojša Popov, Lino Veljak…). The round tables were open to both men and women.

From the middle of the 1980s, women only groups were formed. In Ljubljana, the first women’s group LILITH was founded in 1985, and the first lesbian group Lilith LL in 1987. Lepa Mlađenović in 1986 in Belgrade re-formed and re-founded the feminist group Žena i društvo. Recalling that period, Lepa Mlađenović writes: “Another turning point in the development of feminism and the women’s movement was the date of the founding of the SOS hotline for women and children victims of violence (SOS telefona za žene i decu žrtve nasilja). After the first ten years of elaborating upon and discussing the dimensions of women’s subordination, activists emerged who felt the need to actually work with women directly. Feminists understood that male violence against women traversed all women’s lives and that the development of services for women should begin with the SOS telephone hotline to give a space to women who have survived violence to have their experiences witnessed and believed. The first SOS telephone was established in Zagreb in 1988, followed by Ljubljana in 1989 and Belgrade in 1990. These SOS helplines had identical names, their rules of working and principles were discussed in the same workshops, and in the first women’s camps we spent summers together – the exchange of mutual learning led to a precious kind of feminist politics of solidarity during the wars when political regimes emerged based on the nationalist exclusion of others”.[59] Many of the contacts between women (now from the former Republics) which were established and developed in the 1980s, continued during the wars even though maintaining these links was difficult and dangerous.

At the end of the 1980s, in 1987 to be precise, the first Yugoslav feminist meeting was held in Ljubljana. This was followed by meetings in Zagreb and Belgrade, and the last meeting “Good girls go to heaven, bad girls go to Ljubljana” which was held in Ljubljana in 1991, shortly before the country disintegrated in blood. The wars posed new questions and problems for the women’s movement. Virtually all the particpants in the “Drug-ca Žena” conference remained active, engaged further in the opposition to wars and nationalisms in the 1990s. From the 1990s, the women’s movement has been closely linked to the anti-war movement. The feminist critique of the socialist system which began in 1978 was followed by the critique of the nationalist states which emerged in this region in the 1990s.

References:

BLAGOJEVIĆ, Marina (ed.), Ka vidljivoj ženskoj istoriji: Ženski pokret u Beogradu 90-tih, Belgrade: Centar za ženske studije, istraživanje i komunikaciju, 1998.

BONFIGLIOLI, Chiara, „Belgrade, 1978: Remembering the conference Drugarica Žena. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup? / Comrade Woman. The Women’s Question: A New Approach? Thirty years after“, MA thesis 2008, Utrecht University, Faculty of Arts – Women’s Studies, 2008.

BOŽINOVIĆ, Neda, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku, Belgrade: Devedesetčetvrta: Žene u crnom, 1996.

ĆOPIĆ, Sanja, “Položaj i uloga žene u društvu – Socio-ekonomske osnove položaja žene u društvu” in Sanja ĆOPIĆ- Brankica GRUPKOVIĆ et al., Žene u Srbiji – Da li smo diskriminisane?, Belgrade: Sekcija žena UGS Nezavisnost: ICFTU CEE Women’s Network, 2001.

ČALIĆ, Mari-Žanin, Istorija Jugoslavije u 20. veku, Belgrade: Clio, 2013.

ČIRIĆ-BOGETIĆ, Ljubinka, „Odluke Pete zemaljske konferencije KPJ o radu među ženama i njihova realizacija u periodu 1940-1941. godine“,in Peta zemaljska konferencija KPJ: zbornik radova, (ed.) Zlatko ČEPO-Ivan JELIĆ, Zagreb: Institut za historiju radničkog pokreta Hrvatske: Školska knjiga, 1972, 75-97. http://www.znaci.net/00003/661.pdf (14. 9. 2017).

DREZGIĆ, Rada, „Bela kuga“ među „Srbima“. O naciji, rodu i rađanju na prelazu vekova, Belgrade: Albatros Plus: Institut za filozofiju i društvenu teoriju, 2010.

DUDA, Igor, ”Uhodavanje socijalizma”, in Refleksije vremena 1945. – 1955, Zagreb: Galerija Klovićevi dvori, 2013, 10–40.

ERLICH ST., Vera, Jugoslavenska porodica u transformaciji, studija u tristotine sela, Zagreb: Liber, 1971.

GUDAC-DODIĆ, Vera, „Položaj žene u Srbiji (1945–2000)“, in Žene i deca – Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima XIX i XX veka, (ed.) Latinka Perović, Beograd: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji, 2006, 33-130.

GUDAC-DODIĆ, Vera, Žena u socijalizmu – Položaj žene u Srbiji u drugoj polovini XX veka, Belgrade: Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije, 2006.

JAMBREŠIĆ KIRIN, Renata, ”Moderne vestalke u kulturi pamćenja Drugog svjetskog rata”, in Dom i svijet, (ed.) Sandra PRLENDA, Zagreb: Centar za ženske studije, 2008, 19–54.

JAMBREŠIĆ KIRIN, Renata, ”Žene u formativnom socijalizmu” in Refleksije vremena 1945. – 1955. (ed.) Jasmina BAVOLJAK, Zagreb: Galerija Klovićevi dvori, 2012, 182–201.

KANZLEITER Boris, STOJAKOVIĆ Krunoslav, “1968 in Jugoslawien. Studentenproteste zwischen Ost und West” u dies. (Hg.). 1968 in Jugoslawien. Studentenproteste und kulturelle Avantgarde in Jugoslawien, 1960-1975. Bonn: Dietz-Verlag, 2008, (English translation).

KAZER, Karl, Porodica i srodstvo na Balkanu, Analiza jedne kulture koja nestaje, Belgrade: Udruženje za društvenu istoriju, 2002.

KOPRIVNJAK, Vjekoslav, „Uvodnik u temat“, Žena, 4–5/ 1980, 6–15.

MARKOVIĆ, Ljubica, Počeci feminizma u Srbiji i Vojvodini, Belgrade: Narodna misao, 1934.

MILIĆ, Anđelka, „Preobražaj srodničkog sastava porodice i položaj članova“, in Domaćinstvo porodica i brak u Jugoslaviji: društveno-kulturni, ekonomski i demografski aspekti promene porodične organizacije, Anđelka MILIĆ, Eva BERKOVIĆ, Ruža PETROVIĆ (eds.), Belgrade: Institut za sociološka istraživanja Filozofskog fakulteta, 1981, 135-168.

MITROVIĆ, Mitra, Položaj žene u savremenom svetu, Belgrade: Narodna knjiga, 1960.

MLAĐENOVIĆ, Lepa, Počeci feminizma ženski pokret u Beogradu, Zagrebu, Ljubljani. Available at: http://www.womenngo.org.rs/content/blogcategory/28/61/#zena_i_drustvo (25.09. 2009).

MRKŠIĆ, Danilo, Srednji slojevi u Jugoslaviji. Belgrade: Istraživački centar SSO Srbije, 1987.

NEDOVIĆ, Slobodanka, Savremeni feminizam – Položaj i uloga žene u porodici i društvu, Belgrade: Centar za unapređivanje pravnih studija: Centar za slobodne izbore i demokratiju, 2005.

NEŠ, Kejt (Kate NASH), Savremena politička sociologija- Globalizacija, politika i moć, Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2006.

PETROVIĆ, Jelena, „Društveno-političke paradigme prvog talasa jugoslovenskih feminizama“, ProFemina, 2/ 2011, 59-80.

PETROVIĆ-TODOSIJEVIĆ, Sanja, „Analiza rada ustanova za brigu o majkama i deci na primeru rada jaslica u FNRJ”, in Žene i deca – Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima XIX i XX veka, (ed.) Latinka PEROVIĆ, Belgrade: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji, 2006, 176-187.

PETROVIĆ, Tanja, Yuropa – Jugoslovensko nasleđe i politike budućnosti u postjugoslovenskim društvima, Belgrade: Fabrika knjiga, 2012.

SKELVICKY, Lydia, Konji, žene, ratovi, Zagreb: Druga – Ženska infoteka, 1996.

STOJAKOVIĆ Gordana, „Antifašistički front žena Jugoslavije (AFŽ) 1946–1953: pogled kroz AFŽ štampu“, in Rod i levica, (ed.) Lidija VASILJEVIĆ, Belgrade: Ženski informaciono-dokumentacioni trening centar (ŽINDOK), 2012, 13-39.

STOJAKOVIĆ, Gordana, Rodna perspektiva novina Antifašističkog fronta žena (1945-1953), Novi Sad: Zavod za ravnopravnost polova, 2012.

TODOROVIĆ-UZELAC, Neda, Ženska štampa i kultura ženstvenosti, Belgrade: Naučna knjiga, 1987.

Ustav Federativne Narodne Republike Jugoslavije, 1946 godina, član 24. Available at file:///C:/Users/Hana%20Vestica/Downloads/aj_10_02_10_txt_ustav1946.pdf (15.09. 2017).

VIDMAR-HORVAT Ksenija, Imaginarna majka – Rod i nacionalizam u kulturi 20. stoljeća, Zagreb: Sandorf and Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani, 2017.

VUČETIĆ, Radina, Koka-kola socijalizam. Amerikanizacija jugoslovenske popularne kulture šezdesetih godina XX veka, Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2012.

Žena u privredi i društvu SFR Jugoslavije, osnovni pokazatelji, Beograd: Savezni zavod za statistiku, 1975.

[1] Danilo MRKŠIĆ, Srednji slojevi u Jugoslaviji. Beograd: Istraživački centar SSO Srbije, 1987, 72-92.

[2] Kejt NEŠ (Kate Nash), Savremena politička sociologija- Globalizacija, politika i moć, Beograd: Službeni glasnik, 2006, 117-122.

[3] Ibid, 132.

[4] As Ljubica Marković suggested: „Feminism announced itself here in the beginning of the 1970s, zam se kod nas javlja početkom sedamdesetih godina, as an echo of the braoder women’s liberation movement, which had taken root as an idea across Europe in the 1960s, and partially accepted in the United States. Its origins here can be traced to the start of work on social change and the new social programme developed by Svetozar Marković. With other reformist ideas from the new social movements, the idea of women’s emancipation was accepted from the Russians, from his teacher Černiševski, which were copied and spread in our part of the world“. Ljubica MARKOVIĆ, Počeci feminizma u Srbiji i Vojvodini, Belgrade: Narodna misao, 1934, 4.

[5] For more on the history of the women’s movement inour territorites before World War II, see: Neda BOŽINOVIĆ, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku, Belgrade: Devedesetčetvrta: Žene u crnom, 1996, 20-127.

[6] О privrednoj aktivnost žепа Jugoslavije od 1918. do 1953. from Lydia SKELVICKY, Konji, žene, ratovi, Zagreb: Druga – Ženska infoteka, 1996, 93.

[7] For a detailed mapping of the household structure of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, see: Ibid, 93-96 i 103-107.

[8] For more on the position of women in the inter-war period, see: Vera ST. ERLICH, Jugoslavenska porodica u transformaciji, studija u tristotine sela, Zagreb: Liber, 1971.

[9] Throughout its existence, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia never had a single Civic Code, but rather had six separate legal systems under the strong influence of accepted religious organisations that adopted its own rules on marriage and divorce. Women did not exist as legal subjects in any of these six jurisdictions. The only exception was in criminal law were women were recognized as having reduced capacities. SKELVICKY, Konji, žene, ratovi, 88 i 90. For more on the position of women in the countries which, in 1918, made up the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1929), see:: BOŽINOVIĆ, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku, 91- 103.

[10] Jelena PETROVIĆ, „Društveno-političke paradigme prvog talasa jugoslovenskih feminizama“, ProFemina, 2/ 2011, 63.

[11] Ibid, pp. 59-80. For the history of women’s organizing in Yugoslavia between the two World Wars, see: BOŽINOVIĆ, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku, 104-133; SKELVICKY, Konji, žene, ratovi, 79-81.

[12] Referring to Jera Vodušek-Starič, Mari Žanin Čalić suggests that NOB in May 1945 had around 800,000 armed men and women. Žanin ČALIĆ, Istorija Jugoslavije u 20. veku, Belgrade: Clio, 2013, 207. During the war a total of 305,000 fighters lost their lives, and 425,000 were wounded. Ibid, 209. It is estimated that Yugoslavia at the time of World War II had around 100,000 women fighters, 25,000 died, 40,000 were wounded, and 3,000 survived but with severe disabilities. 90 women were proclaimed heros. Žena u privredi i društvu SFR Jugoslavije, osnovni pokazatelji, Belgrade: Savezni zavod za statistiku, 1975, 3.

[13] „Drug Tito nama i o nama“ in Žena danas, 31/ 1943. no. 3 based on BOŽINOVIĆ, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku, 147.

[14] SKELVICKY, Žene, konji, ratovi, 25-28.

[15] Ljubinka ČIRIĆ-BOGETIĆ, „Odluke Pete zemaljske konferencije KPJ o radu među ženama i njihova realizacija u periodu 1940-1941. godine“, in: Zlatko Čepo and Ivan Jelić (eds.), Peta zemaljska konferencija KPJ: zbornik radova, Institut za historiju radničkog pokreta Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1972, 94. Web: http://www.znaci.net/00003/661.pdf (14. 9. 2017)

[16] PETROVIĆ, „Društveno-političke paradigme prvog talasa jugoslovenskih feminizama”, 76.

[17] SKELVICKY, Konji, žene, ratovi, 30.

[18] Gordana STOJAKOVIĆ, Rodna perspektiva novina Antifašističkog fronta žena (1945-1953), Novi Sad: Zavod za ravnopravnost polova, 2012, str. 37- 38. The AFŽ publishing system was hierarchically based with Žena danas as a monthly publication which carried axiomatic messages from the leaders of the middle and lower committees of AFŽ, and all other publications based on the presented framework explored realities at the macro- (political plans) and micro-levels (everyday life) which they themselves were also contributing to in terms of new roles for women. The presentation of women as active agents in the transformation of the socio-economic context in factories, in the fields, and in agricultural co-operatives was a characteristic of the post-war AFŽ press in the perdio from 1946 to 1950. At the same time, important roles of women continued to be within the economy of care, as well as in the role of mothers (of their own children and of children who were without parents) Ibid, 169-173. See also: Ksenija VIDMAR-HORVAT, Imaginarna majka – Rod i nacionalizam u kulturi 20. stoljeća, Zagreb: Sandorf and Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani, 2017, 45-58.

[19] “Politika”, 28 October 1950 based on Vera GUDAC – DODIĆ, „Položaj žene u Srbiji (1945–2000)“, u Žene i deca – Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima XIX i XX veka, (ed.) Latinka Perović, Belgrade: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji, 2006, 35.

[20] Gordana STOJAKOVIĆ, „Antifašistički front žena Jugoslavije (AFŽ) 1946–1953: pogled kroz AFŽ štampu“, in: Rod i levica, Lidija VASILJEVIĆ (ed.), Ženski informaciono-dokumentacioni trening centar (ŽINDOK), Belgrade, 2012, 13.

[21] Igor DUDA, ”Uhodavanje socijalizma”, Refleksije vremena 1945. – 1955, Zagreb: Galerija Klovićevi dvori, 2013, 25.

[22] Coupons r1 and r2 for workers, and coupon 0 for everyone else, whilst peasants had no right to coupons. In addition, r1 coupons could be used in a variety of shops, unlike r2 coupons. Renata JAMBREŠIĆ KIRIN, ”Žene u formativnom socijalizmu”, Refleksije vremena 1945. – 1955. (ur.) Jasmina BAVOLJAK, Zagreb: Galerija Klovićevi dvori, 2012, 193.

[23] See JAMBREŠIČ-KIRIN, ”Moderne vestalke u kulturi pamćenja Drugog svjetskog rata”, ”, in Dom i svijet, (ed.) Sandra PRLENDA, Zagreb: Centar za ženske studije, 2008,19-54.

[24] VIDMAR HORVAT, Imaginarna majka – Rod i nacionalizam u kulturi 20. stoljeća, 46. On the political representation of motherhood see: ibid, 46-67. On the politics of motherhood see also: Rada DREZGIĆ, „Bela kuga“ među „Srbima“. O naciji, rodu i rađanju na prelazu vekova, Belgrade: Albatros Plus: Institut za filozofiju i društvenu teoriju, 2010, 17-51.

[25] Tanja PETROVIĆ, Yuropa – Jugoslovensko nasleđe i politike budućnosti u postjugoslovenskim društvima, Belgrade: Fabrika knjiga, 2012, 158 (footnote).

[26] According to the Decree on the Protection of Empoyed Pregnant Women and Nursing Mothers (Uredbe o zaštiti zaposlenih trudnih žena i majki dojilja), 90 days of maternity leave were envisaged and, in some cases, a shortened four hour working day was possible until the child reached the age of three. Employed mothers who were breastfeeding were allowed to stop work every three hours, in order to breastfeed the child, a right which could be used for six months after the birth. Maternity leave was compensated to the level of a full salary. Mothers who were single parents or whose children had additional needs and who worked a four-hour day were compensated for 75% of their income. In later stages of social development, the period of paid maternity leave was extended on a number of occasions, up to one year after the child’s birth. GUDAC-DODIĆ, „Položaj žene u Srbiji (1945-2000)“, 37.

[27] VIDMAR HORVAT, Imaginarna majka – Rod i nacionalizam u kulturi 20. stoljeća, 47-49.

[28] AFŽ as a special women’s organization was abolished at the IV Congress in 1953. Various organisations and societies who were concerned with questions of interest to women united as the Federation of Women’s Associations of Yugoslavia (Savez ženskih drustava Jugoslavij, out of which was formed the Conference for the Social Activities of Yugoslav Women (Konferencija za društvenu aktivnost žena Jugoslavije) in 1961 in Zagreb. It worked under the auspices of the Federation of the Socialist Working People of Yugoslavia – SSRNJ (Savez socijalističkog radnog naroda Jugoslavije). Neda Božinović, a Partisan of the time, amongst other things in charge of Partisan Monuments 1941 (Partizanske spomenice 1941) and an active member of AFŽ after the war, noted that “the decision to abolish AFŽ, or rather to found the Federation of women’s societies, was experienced by a large number of delegates as a downgrading of women’s organisations and or women themselves. Many activists from AFŽ reacted to the decision by stopping their work completely. … After a while, women, particularly in villages, confronted women leaders with the accusation “you abolished our AFŽ!”. They told of how men would taunt them “enough of yours” or “it’s finished, it’s finished” or “it’s no more”. They recalled how man still had, constantly, their cafes, their football, even their People’s Front, whereas women had nowhere to get together, and longed for conversations about their “women’s questions”. BOŽINOVIĆ, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku, 174.

[29] The participation of women in decision-making bodies from the end of the war was constantly falling. The 1949-50 elections for National Councils there were two thirds as many women as there were for the elections two later. Already by 1963 in the Federal Assembly the proportion of women was 15.2%. Six years later it had fallen to 6.3%. Žena u privredi i društvu SFR Jugoslavije, osnovni pokazatelji, 4; BOŽINOVIĆ, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u 19 i 20 veku, 249.

[30] Vjekoslav KOPRIVNJAK, „Uvodnik u temat“, Žena, 4–5/ 1980, 10.

[31] „The participation of women in the total of those employed in the social sector showed a constant increase: in 1945 it was 29.3%, in 1982 it had reached 36.5% and in 1986 it was 38.0%. This trend is comparable to those in developed European countries. However, the particpation rate of women in the totla employed ranged considereably in different parts of the country. While in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, it reached 45.8%, in SR Croatia 40.9%, whilst in SR Macedonia it was 34.7%, SR Montenegro 35.6% and in the Socijalist Autonomous Territory of Kosovo it was 22.1%. Statistics from Izveštaja SFRJ o primeni konvencije o ukidanju svih oblika diskriminacije žena (Report of Yugoslavia for the CEDAW), June 1983. p. 18 and SGJ for 1986, „Statistički bilten SZS“ no. 15777, 1986, according to Slobodanka NEDOVIĆ, Savremeni feminizam – Položaj i uloga žene u porodici i društvu, Belgrade: Centar za unapređivanje pravnih studija: Centar za slobodne izbore i demokratiju, 2005, 108.

[32] „After World War II the number of illiterate population older than 10 constantly fell; according to the 1948 census there were 26.7% illiterate people, the rate for men was 15% and for women 37.5%. By 1981, the rate of illiterate people was 10.8%, but there were four times as many illiterate women as men; in the 1991 census the percentage fell to 6.2% but, again, the percentage of women was higher, at 6.2%, compared to a rate of 2,2% for men. Sanja ĆOPIĆ, “Položaj i uloga žene u društvu – Socio-ekonomske osnove položaja žene u društvu” u Sanja ĆOPIĆ- Brankica GRUPKOVIĆ et al., Žene u Srbiji – Da li smo diskriminisane?, Belgrade: Sekcija žena UGS Nezavisnost: ICFTU CEE Women’s Network, 2001, 29.

[33] „Women are equal to men in all spheres of state, economic and socio-political life» (Žene su ravnopravne sa muškarcima u svim oblastima državnog, privrednog i društveno-političkog života“), Constitution of the Federation of Yugoslavia 1946, Article 24. Available at: file:///C:/Users/Hana%20Vestica/Downloads/aj_10_02_10_txt_ustav1946.pdf (15.09. 2017).

[34] Based on statistics published in Bilten SZS (no. 1181 from 1981) on salary levels of those employed based on gender and qualifications for 1976, Slobodanka Nedović writes: „The average personal income of women is lower than that of men (with the same level of qualifications) in every category of work except in water management. In industry the difference ranges from 11% in the group of unqualified workers, to 33.8% in the group of qualified workers, 32.6% amongst the most highly qualified, and 21.7% amongst those educated to university level, all to the advantage of men. The data point to the existence of a direct form of discrimination against women, who find it harder to obtain managerial positions, wait longer for promotions and generally have fewer opprtunities for more complex, responsible and, therefore, higher paid, positions. It is an unwritten rule that even in work places were women make up the majority of the workforce, the majority of managers will be men.“ Slobodanka NEDOVIĆ, Savremeni feminizam – Položaj i uloga žene u porodici i društvu, Belgrade: Centar za unapređivanje pravnih studija: Centar za slobodne izbore i demokratiju, 110.

[35] GUDAC-DODIĆ, „Položaj žene u Srbiji (1945–2000)“, 64.

[36] Karl KAZER, Porodica i srodstvo na Balkanu, Analiza jedne kulture koja nestaje, Belgrade: Udruženje za društvenu istoriju, 2002, 441.

[37] STOJAKOVIĆ, Rodna perspektiva novina Antifašističkog fronta žena (1945-1953), 69

[38] Anđelka MILIĆ, , „Preobražaj srodničkog sastava porodice i položaj članova“, in: Domaćinstvo porodica i brak u Jugoslaviji: društveno-kulturni, ekonomski i demografski aspekti promene porodične organizacije, Anđelka MILIĆ, Eva BERKOVIĆ, Ruža PETROVIĆ (eds.), Belgrade: Institut za sociološka istraživanja Filozofskog fakulteta, 1981, 157.

[39] See: Sanja PETROVIĆ-TODOSIJEVIĆ, „Analiza rada ustanova za brigu o majkama i deci na primeru rada jaslica u FNRJ”, in Žene i deca – Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima XIX i XX veka, (ed.) Latinka Perović, Belgrade: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji, 2006, 176-187.

[40] Vera GUDAC DODIĆ, Žena u socijalizmu – Položaj žene u Srbiji u drugoj polovini XX veka, Belgrade: Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije, 2006, 107.

[41] Ibid, 108.

[42] For all three quotes taken from the survey „Kako da se pomogne zaposlenoj ženi“ (Praktična žena, June, 1956) I am grateful to Jelena Tešija who drew them to my attention.

[43] Mitra MITROVIĆ, Položaj žene u savremenom svetu, Belgrade: Narodna knjiga, 1960, page 8.

[44] Radina VUČETIĆ, Koka-kola socijalizam. Amerikanizacija jugoslovenske popularne kulture šezdesetih godina XX veka, Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2012, 32-40.

[45] Neda TODOROVIĆ-UZELAC, Ženska štampa i kultura ženstvenosti, Belgrade: Naučna knjiga, 1987, 113-133.

[46] As Božidar Jakšić formulated it: “They [… students] also had access to books and texts of critical intellectuals in the East and the West. The works of Herbert Marcuse, for example, one of the intellectual founders of the New Left, was published in Serbo-Croatian from 1965 on. Other works of philosophers from the Frankfurt school were alsowidely published. In the magazine Praxis, which was edited by university professors in Belgrade and Zagreb, the discourses of the New Left were discussed.35 At an annual summer school on the Croatian island of Korčula near Dubrovnik, critical intellectuals including Marcuse, Erich Fromm, Lesek Kolakowski and Ernest Mandel were frequent guests. Every year between 1964 and 1974, hundreds of Yugoslav students were able to participate in discussions with them.” Božidar Jakšić ”Praxis i Korčulanska ljetnja škola. Kritike, osporavanja, napadi”, cited in Boris KANZLEITER, Krunoslav Stojaković, “1968 in Jugoslawien. Studentenproteste zwischen Ost und West” in 1968 in Jugoslawien. Studentenproteste und kulturelle Avantgarde in Jugoslawien, 1960-1975. Bonn: Dietz-Verlag, 2008, (translated into English), 15.

[47] Ibid, 13.

[48] Chiara BONFIGLIOLI, „Belgrade, 1978: Remembering the conference Drugarica Žena. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup? / Comrade Woman. The Women’s Question: A New Approach? Thirty years after“, MA thesis 2008, Utrecht University, Faculty of Arts – Women’s Studies, 2008, 51.

[49] „I will tell you, for me it was very important as it was the first conference type event with feminist agenda trying to bring people from Belgrade and Zagreb and elsewhere in Yugoslavia together, plus a lot of people from abroad. There were some eighty people there in these two days. So the core feminist group was trying to go from this very small intellectual circle a little bit broader, bring some younger students and get some media attention. It was an exploration and an agenda settinf meeting, and much of networking… and it was fascinating to get all these people from abroad, all of quite different orientations. It was very dynamic and polemic, but of course all slowed down by translations. So there was Italian to English, English to Serbo-Croatian, German, French, Spanish… (…) So I remember 80 people sitting there two days and socialising in the evening hours and questioning each other with utmost curiosity.“ BONFIGLIOLI, „Belgrade, 1978: Remembering the conference Drugarica Žena. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup? / Comrade Woman. The Women’s Question: A New Approach? Thirty years after“, 53-54.

[50] Dragan Klaić: „You have to understand that we were criticising Yugoslav self- management socialism as such. We were criticising the sexist elements of the Yugoslav’s system with which we identified in general. In that sense it wasn’t a radical critique of Yugoslav socialism… These were progressive leftist intellectuals, but anti-dogmatic, critical, especially of the official Yugoslav ideology and the ideological jargon and the ideological fasade, but not anti-socialist… and with a steady critical analysis of capitalism, as well“. Cited in BONFIGLIOLI, „Belgrade, 1978: Remembering the conference Drugarica Žena. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup? / Comrade Woman. The Women’s Question: A New Approach? Thirty years after“, 100.

[51] An exceptionally good example of this can be seen in Helke Sander’s film Subjective Factor (Der subjektive Faktor) from 1981. This is a semi-autobiographical review of the period between 1967 and 1970 which Helge spent in West Berlin, where she studied at the Deutsche Film und Fernsehakademie. She was actively involved in the student movement of ’68 and was one of the founders of The Action Council for the Liberation of Women (Aktionsrat zu Befreiung der Frauen) in 1968. The film includes her speech in September 1968 at a conference of the Socialist Student Association where she attacked the secist attitudes of her male counterparts. After the Association refused to discuss feminist demands and patriarchy in their own organization, the Action Council for the Liberation of Women decided to throw tomatoes at men speaking from the podium.

[52] Ewa Morawska: “So you have here three phases: the West with its bubbling feminist debates and and legal adjustments; Yugoslavia with its very vibrant interest in what’s going on in the West, and Eastern Europe where nobody heard of feminism and whatever they heard was „ugly lesbians“. Cited in BONFIGLIOLI, „Belgrade, 1978: Remembering the conference Drugarica Žena. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup? / Comrade Woman. The Women’s Question: A New Approach? Thirty years after“, 78.

[53] Ibid, 86.

[54] The sociologist in question is Slobodan Drakulić

[55] BONFIGLIOLi, „Belgrade, 1978: Remembering the conference Drugarica Žena. Žensko pitanje. Novi pristup? / Comrade Woman. The Women’s Question: A New Approach? Thirty years after“.

[56] Rada Iveković: “Before the conference we did not exist. We happened during that conference. We did not know each other, Zarana put all of us together, and we were not a group. We hadn’t the awareness that we could represent something. During that conference we understood that we were many, and that each one of us did some feminist work, a bit of research, of critique.” Cited in Ibid, 86.

[57] For a detailed programme of events at SKC,see: Marina BLAGOJEVIĆ (ur.), Ka vidljivoj ženskoj istoriji: Ženski pokret u Beogradu 90-tih, Belgrade. Centar za ženske studije, istraživanje i komunikaciju, 1998, 49- 60.

[58] Lina VUŠKOVIĆ, Sofija TRIVUNAC „Feministička grupa Žena i društvo“in Ka vidljivoj ženskoj istoriji: Ženski pokret u Beogradu 90-tih, (ed.) Marina Blagojević, Belgrade. Centar za ženske studije, istraživanje i komunikaciju, 1998, 47- 48.

[59] Lepa MLAĐENOVIĆ, Počeci feminizma ženski pokret u Beogradu, Zagrebu, Ljubljani. Available at: http://www.womenngo.org.rs/content/blogcategory/28/61/#zena_i_drustvo (25.09. 2009).

[*] This text is an extended version of the text “Proleteri svih zemalja – ko vam pere čarape? – Feministički pokret u Jugoslaviji 1978-1989”, published in 2009 in “Društvo u pokretu – Novi društveni pokreti u Jugoslaviji od 1968. do danas”. Đorđe Tomić, Petar Atanacković (eds.), Društvo u pokretu – Novi društveni pokreti u Jugoslaviji od 1968. do danas, Novi Sad: Cenzura, 2009.