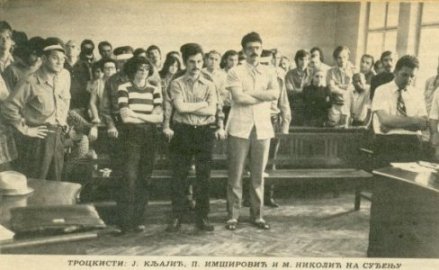

Sentencing 1972, Jelka Kljajič, Pavluško Imširović, Milan Nikolić

In this autobiographical political text, the author writes about her experiences in the ’68 student dissent milieu in Belgrade in the period after the ’68 rebellions, and details the state repression through which she lives due to her affiliation with the milieu. The text was originally published in the newspaper Republika, while here we publish an abridged version.

Jelka Kljajić-Imširović

Dissidents

The worsening of repression decisively influenced, in my opinion, within the student movement a rise of ideas, better said as thinking about the possibilities and strategies of resistance in the “long term.” In the circles I was moving in, primarily those of students, but not only students, we thought of revolutionary social theory and the revolutionary workers party as two important assumptions and, at the same time, factors of transformation from the contemporary repressive class society into a true socialist society. What number of people are we talking about? By my recollection, and I admit that it may not be completely reliable, in that circle – I use this term deliberately, and not, for example, the term “group” – there were no more than about 20 people. Our ideological and theoretical standpoints were based on Marx’s works and Marxism, creative Marxism, as it was called at the time, and also Marxism separate from Soviet, hardline “Marxism.” It is understood that there were significant differences in perceptions, and around some important Marxian conceptual assumptions, between some Marxist theorists and revolutionaries. For example, I thought the works of Rosa Luxemburg were more relevant to understand and that the time in which she lived were more applicable to our contemporary life than the works of Leon Trotsky. For Pavluško Imširović, she was important as a revolutionary, but not as a revolutionary theorist. He was in line with Lenin’s assessment that Rosa was “despite all her misconceptions, the eagle of the revolution.”[1]

One topic which was discussed frequently in such a Marxist “circle” was the Praxis school. “The main stage” in discussions was held by us 5 to 6 then-young sociologists. For us, as for the majority of those who continued the rebellion of the student movement, Praxis critical philosophy was the most important Marxist critical thought in our society. However, it was a line of thought which, in our opinion, deserved serious criticism. Milan Nikolić and I brought out some of our own critiques and analysis of the Praxis school at the Korčula summer school of 1971. The essence of our critique was, first, that the majority of theoretical work of the Praxis group stayed in line with academic philosophy and, second, that their critiques of contemporary society, specifically Yugoslav society, were far too general, that is to say, lacked concrete criticism. That form of social critique, in my opinion, was the logical consequence of theoretical-methodological concepts which thought of revolution as defined by philosophy. It was just in that way that the journal Praxis (1964) defined the concept of revolution in their program. That which was ascribed to philosophy, i.e. that it should be “a ruthless critique of all that exists, a humanistic vision of a truly human world, and the inspirational power of revolutionary action,” can be realized, I thought, only in the realm of critical social theory. I thought, primarily, of the insight of the critical social theories of Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse (1973 – Traditional and Critical Theory; Philosophy and Critical Theory).

The most prominent representatives of the Frankfurt School during World War II abandoned such a concept of critical theory. Their critical thought regarding contemporary society increasingly became critical philosophy. In that sense I drew a parallel between the Frankfurt School and the Yugoslav Praxis school. The Frankfurt theorists explained their abandonment of the original conceptualization of critical theory due to the fact that contemporary repressive society, in which the working class is integrated into the system, can no longer be explained in the categories of Marx’s political economy. In the Praxis school, the importance of the critique of political economy is not explicitly denied, but the sphere of the economy is on the periphery of critical consideration. Some key economic phenomena and relationships, like in the later Frankfurt School, come through in the sphere of the philosophical theories regarding alienation and objectification. Similarly for Marx’s thesis, and not only Marx’s, regarding the proletariat as a revolutionary subject. I mentioned that I understand some positions of the Praxis school as the negation of this thesis. [2] In my Korčula critique of the Praxis school, I spoke of the differences which exist inside this current of critical Marxist thought in regards to the terminological and methodical categorization of societies in which political oligarchies invoke Marxism and socialism. Some authors wrote of administrative, bureaucratic, state socialism (R. Supek), some of “statist-socialism,” “despotic socialism,” an even “despotic communism” (Lj. Tadić). And other authors used, if more rarely, these terms: In critical texts distributed among the Praxis school, they spoke of “Stalinist socialism.”

The term self-managed socialism was used with or without quotes (as primarily an ideological construct and a society towards which critical theory aims). For most authors, who published their critical works in the journals Praxis and Filozofija, and more and more frequently in Sociologija, these forms of designations – with reason, in my opinion – were unacceptable. Some decidedly insisted that there was no crisis of socialism today, but a crisis of the notion of socialism (D. Grlić, M. Životić…). S. Stojanović and M. Kangrga thought that one could speak of a new form of class society. S. Stojanović defined this new class society as statism. M. Kangrga defined it as a political (civil) society. When the question of a new class formation arises, I thought it logical that it could not be called socialist. Calling a society in which class relations are made and reproduced means denigrating the very idea of and struggles for socialism. In the end, I will mention one more objection I directed at the Praxis-ists that year, long ago. It is about the tying of Stalinism to Soviet society. They did this, in my view, explicitly and implicitly, both the Praxis-ists who thought of Stalinism as a negation of socialism, and those who, along with a sharp critique of it, nevertheless classified it as a form of socialism. Without an analysis of the Stalinism of KPJ [Komunistička partija Jugoslavije – Communist Party of Yugoslavia], I thought, there is no concrete critical analysis of Yugoslav society.[3]

What was the idea behind, and was anything accomplished with, the foundation of the Revolutionary Workers’ Party? I already mentioned that one key slogan of the student protests, here and in the world, was “students – workers.” For the rebelling students, and not only students, and after ’68, there was an understanding and questioning and interest in the potential and preconditions of the revolutionary workers’ movement. The critique of the ideological assumptions of the ruling assemblages, in which they, i.e. the ruling party, framed themselves as the real representatives in the interest of the “ruling working class” (already in that time it was more frequently added, “and the working people, and nations and nationalities”), was a “daily theme” for consideration and reflection in the sphere of an alternative, critical, public.

The party-state elite, who were qualified among the critical public most often as the core of the new ruling class (which was also called the managerial class, statist class, partocracy, bureaucracy…) often, in various forms, asked the questions: how do the members of the “ruling class” more frequently end up without jobs, why do they strike, why are they massively leaving for Germany and other wealthier Western nations, what right do the contemporary authorities have to ask for our workers to have more rights in those countries than the workers had or have in our own country? I remember that at one tribune at the Faculty of Philosophy (…) all of the questions were asked to one city union official (Đorđe Lazić). Faced with a multitude of such questions and sub-questions, in one moment he began to explain economic migration as “a natural drive for pečalba.” [pečalba – an archaic term for seasonal wage work done by migratory workers, often abroad] To that I asked, how is it that only workers “love pečalba” but not politicians, union officials… He claimed that strikes were not a form of class conflict in our society. His answers were confusing, like all other official explanations. [4] For me, like some other participants in the tribune, the increasingly larger number of strikes, increasing unemployment and the departure of our workers abroad showed the intensification of class relations in society and the sparking of the workers’ movement.

Until around spring 1971, I saw revolutionary change first and foremost as spontaneous growth and revolutionization of worker’s movements. Or, more precisely said, I thought that the working class, its social position, spontaneously leads towards the movement for radical societal change about which the rebelling students and critical social theorists spoke. Until then, I rarely thought about a new workers’ party. And when I began to think about that more intensively, I was relatively skeptical. I had in mind the fact – in my perception a fact – that in the revolutions of the 20th century, all larger and/or more influential workers’ parties had a particularly negative role, a role of suppression and stifling of workers’ movements. I thought of Western social-democratic parties which, during World War I, voted in their parliaments for war credits, that is to say for war, I thought of the role of the German social democracy, specifically its leadership, in suppressing the November Revolution Councils and the murders of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, of the Bolshevik suppression of the Kronstadt uprising and the prohibition of the workers’ opposition of Shliapnikov and Kollontai…

In the circle of people who thought that the Revolutionary Workers’ Party was a necessary factor for revolutionary societal change, the problems I mentioned previously were discussed frequently and at length. Discussions of that nature were not secretive. That means, as well, for discussions regarding reform and revolution, revolution and power, the workers’ movement and the party… In such situations the discussants did not concern themselves with, for example, whether roommates or guests entered a student dorm room. The discussions that took place took a “second turn” if before that there was a discussion about the Stalinist character of the SKJ [Savez Komunista Jugoslavije – League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the new name of the Communist Party], the relations between KPJ and SKP(b) [The Soviet Communist Party], the manner by which J. Broz came to be the head of the KPJ, the suffering of prominent officials of the KPJ in Siberian gulags. In all discussions, the most conspiratorial was, actually, the idea of the Revolutionary Workers’ Party here and now. The concreteness of that idea, until the end of 1971, did not move far from theoretical conversations and debates about goals and possibilities, ideals and social situations in such an organization. Really, that idea was made “concrete” because it was thought that the Initiative Group for RRP (RWP) should be the first, small, step towards forming a new party. However, even that group did not exist. Unless we think of it so broadly as to understand it as the group of people who, in their own ways, strives, wants, and thinks about how to establish the RRP (RWP). Among those people there were those who thought about this systematically and “at length,” as well as those for whom, for whatever reason, it was a “in the moment” inspirational idea. One version of the goals and organization of the form of the future RRP (RWP) was Milan Nikolić’s paper, “signed” IG RRP. It was the only version in written form. There were also ideas and stances that were previously discussed, with which other people agreed, but, above all, it was Milan’s text. Therefore, there was neither a written text under the authority of a “group,” nor a text which was accepted as the political platform of the “group.” [5] Instead of a group – as I mentioned – it is more correct to speak of a sphere or circle of people who, by their own intentions, were only then supposed to grow into an Initiative Group for the Revolutionary Workers’ Party. Whether that would have happened, if the arrests hadn’t occurred, falls within the domain of stories about “What would have happened if it had happened.” Judging by the zeal, seriousness, and knowledge of some people in our “revolutionary debate club” I think that it would have happened in some foreseeable future, or at least would have started to happen. Most likely, by my estimation, without some larger success.

Vladimir Mijanović, Jelka Kljajić Imširović, Snežana Radovanović, Dragiša

Arrest and Prison

The speech by Branko Pribićević, president of the UK SK BU [University Committee of the League of Communists of the Belgrade University], professor at the FPN [Faculty of Political Sciences], announced a new phase of clashes. Somewhere near the end of November or beginning of December, if I remember correctly, he presented a terrifying speech about the “Trotskyist Troikas” at the University of Belgrade. For the first time since the Second World War, Trotskyists were mentioned as a real danger, that is to say enemies of the state, system, self-management… In the first few years after the war, Trotskyism and Trotskyists were mentioned in political speeches and in various party documents, but as a thing of the past. Whoever knew the truth about the history of the party (KPJ) and further, Stalinism, knew that verbal attacks on Trotskyists foreshadow arrests. About that same time, there was a reprint of Proleter [Proletarian], the party newspaper which circulated between the two world wars. I only paged through it then (in prison I read it thoroughly) and it was more than obvious to me that those who the authorities suspect as Trotskyists will not be treated kindly. (B. Pribićević later “fallen” out of party functions under charges of being a liberal.)

I could have said, to myself and others, that I am not a Trotskyist, but, after Pribićević’s speech, I knew that I could still be arrested. I had no illusions that the authorities who announced a pointed crackdown on Trotskyism had an ear for such nuances as to what it is to be a Trotskyist, treating Trotsky and Trotskyists as people who, entirely and/or partially opposed Stalinism. I additionally didn’t have illusions that the authorities, due to their own needs, wouldn’t pin the badge of Trotskyism to people who had no public stance towards Trotsky and Trotskyists. I didn’t know, nor could I have known, how many “Trotskyists” the prosecuting authorities, according to political command, could fabricate. Nor was I sure why specifically the “Trotskyists” were talked about as Troikas. [6] Shortly after Pribićević’s speech came the first apartment search and interrogations which more or less explicitly “circled” around Trotskyism. It was about one professor of Sociology. His name wasn’t announced publicly, so I won’t announce it either. It was somewhere around New Year’s 1972. On the 7th of January in 1972, therefore on Christmas, Milan Nikolić and Pavluško Imširović were arrested. Svetlana Vidaković, then Milan’s girlfriend, was also interrogated. From her I found out that my friends were arrested and that their chances of being released were nil. The next day it was confirmed that was the case. Namely, then, under the ZKP [criminal proceedings law], a person could be held in custody for 24 hours without a decision to initiate an investigation against them. Both Milan and Pavluško were charged with “reasonable doubt” that they committed crimes under Article 117, paragraph 1 of the criminal law of SFRY [ZK SFRJ] (“associating against the people and state”) and Article 118, paragraphs 1 and 2 (“enemy propaganda,” in layman’s terms “ordinary,” and “in conjunction with foreign interests”). At the time I didn’t know much about the XV chapter of the KZ (criminal acts against the people and state), but I learned “on the fly” that there is no “enemy association” without at least three people. The conclusion was obvious – the arrest of at least one more, third, person was coming. A few days later, my and Pavluško’s friend, a Russian exchange student, Vladimir – Volodya (whose last name I regrettably don’t remember), was kidnapped in the Penezić student dorms. He was deported to the USSR. The KGB and SDB were, obviously, cooperating well. Volodya’s poor mother, whose “ears they filled,” without a doubt, with stories of her son’s “enemy activities,” came to Belgrade. However, they had already taken Volodya away. She left the same day. Volodya’s colleague, a Sudanese student, told me how and what happened that day in not-quite-good Serbo-Croatian. I felt guilty and sad that I hadn’t seen Vladimir’s mother. Volodya, a student, as far as I remember, of the Mining Faculty, came to Belgrade as a Brezhnevist Komsomol member [Soviet Communist youth organization]. In the moment he was captured, he was, according to his convictions, a Soviet dissident. I don’t know whether because of legal regulations or something else, Volodya wasn’t linked to the “enemy Trotskyist Troika” here.

After Pavluško and Milan’s arrest, and especially after Volodya’s abduction, each day it became ever more clear to me that I was entering the increasingly narrow circle of “options” for the third defendant. Until I was arrested, I wasn’t sure that I would be the third one. I found I was the “shortlisted candidate” from the intensification of my monitoring. From ’68, I frequently listened to stories about monitoring and avoidance, i.e. escaping unwanted escorts. That’s one of the typical dissident stories. Those, mostly “male stories,” irritated me a bit. My stance was, “it’s theirs to follow us; ours to ignore them.” I know, it was easier for me to say that than for many people. Either, as I’m convinced, the DB [State Security police] did not follow me for long (I wasn’t a “significant person” from their point of view), or it was quite easy for me, in view of my shortsightedness, to “ignore” what I did not notice. Two to three weeks before the arrest, despite my principled attitude, it wasn’t easy to ignore the surveillance and spies. The Resident Assistant (RA) of the women’s bloc at Penezić began to inform my friends and acquaintances that I wasn’t in my room, and when I left. And he informed me about who came looking for me, sometimes with a name, other times with a description of the person (people). Until about a month before, he would have had to look at the book of residents to find out whether I’m there and which room I’m in. My two roommates’ department colleagues began to come to our dorm room, when they never had before. And more or less these “colleagues” instigated conversations on political topics with me, and showed noticeable interest in “my” books. I say “my” in quotations as there were also many of a friend’s books whose apartment was the first to be searched, along with Pavluško’s books which I brought to my room after he was arrested, and a few of Volodya’s books which his colleagues gave to me. I did not think it was dangerous to have that many books and journals of that sort, as, in the end, the books had all already gone through police triage. It was obvious to me that the guests of my roommates were police informants. My roommates apologized to me after the visits. They were also aware of the purpose of the visits. I’m convinced that they were not involved in the informant work in any way. I couldn’t force these “types” out of the room. How would you kick out your roommate’s guest or guests? “The guests” came by a few times, in different forms. Had anybody I had known personally acted like these “guests” I would have chased them out of the room “just like that.” [7] In the end, the monitoring took on the form of direct intimidation. Someone, while I was working at night in the dorm reading room, acted like a maniac. When I finally understood that the “commotion” I heard periodically wasn’t coming from branches hitting the glass walls of the room, and when in the dark I saw some man outside, “my heart dropped to my heels.” I gathered my papers off the table, better said grabbed, and rushed out. The Resident Assistant wasn’t at the door. Someone ran after me up until the second floor. For a “long” time I heard tapping on the floor. Only when I, “as though without a soul,” crashed into bed did I realize this didn’t have anything to do with an “ordinary maniac.” That was, I’m sure, either the RA-informant, or one of his “pals.” He, whoever he was, didn’t intend to do anything else but “properly” scare me. “Figuring this out” was a small consolation for the fear I experienced.

Two days after that, in the early morning, two DB [State Security] officers “fell into” my dorm room. With them, “my favorite” RA. That was on the 21st of January, 1972. The arrest, by custom, was preceded by an apartment search, that is, in my case, my dorm room. Despite being in a fog, I instinctively recognized one of the DB officers. In the student circles he was the “famous” Panta (Pantelić). Before that day, I had never seen him in my life. But, by others’ descriptions, I learned that I was correct that one of the DB officers was indeed Panta. When I looked at my executioners, “my heart pounded like crazy,” and in my stomach there was a “cold anxiety,” but, I also felt a sense of relief. Relief because it was evident now that I was the “third man.” There was no more uncertainty. The search was thorough. They separated and “confiscated” a bunch of books and journals. They seized the diaries from my high school and university days. Not one word from those diaries was used in the research process, but my diaries are gone. I assume that they are long recycled. I never journaled again.

After the search, Pantelić and Krivokapić (a law student, as he introduced himself as) took me to the SDB [State Security Service]. Immediately they tried to interrogate me. Panta aggressively, Krivokapić in a soft tone. Whether it was a division of roles or a difference of personality, I don’t know. They asked me mainly about the books. They asked me questions, also, about Pavluško and Milan… To their questions I asked whether I was arrested. To that, they told me that it’s uncertain and that much of it rests on me. They interrogated me and some others in other rooms. Similar questions – same answers. One irritable man – I concluded from the way his predecessor in the interrogation had behaved towards him that he was some significant “big shot” – yelled at me and with a threatening tone told me that I was arrested. I asked for a lawyer. He exited the office, screaming. For a long time, there was no one else. I fell asleep in the armchair. It was already nighttime when two people led me to the car and drove me to the City Police Station. I was there for at least an hour or two in some basement room. In the end, dazed from exhaustion, they took me to the investigating judge. That was Svetislav Stevović. He didn’t even attempt to interrogate me. He asked me for my personal information – generalije, as it’s said in the judicial terminology – and dictated them to his secretary. Two uniformed police “stuffed” me into a squad car and took me to the central jail. During the search, this time of me, they took my belt, shoelaces, coin purse… They gave me two disgusting rough blankets and “expelled” me to a solitary cell. In front of the cell, the policeman told me that I can bring in cigarettes, but not a match. He explained to me that a match is placed above the door, and that, during the day, a guard will come every hour to light a cigarette for smokers. That was the first rule of prison life that I was told. In the cold cell, without light, I barely found the bed, that is, in jail slang, “palace.”

The first ten days in prison are the hardest. I couldn’t eat for at least 4 to 5 days. I couldn’t handle the stench of the ammonia which emanated from the open toilet. The solitary cells are designed to make the prisoner’s life worse. There is no electric light in them. Nor a radiator. The daylight is weak. The cell window, a small opening near the ceiling, covered by some kind of wire, “looks” into the prison hallway, and the hallway onto the high walls of the prison yard. But, with time a person gets used to it. When my first packages arrived with bedding and clothes, and with that books, the cell no longer looked as scary. My friends even got a newspaper subscription for me. With the help of my lawyer, a delightful man and an extraordinary professional, I fought to get a pen. Discovering that my friends had not forgotten about me and that my parents support me meant a lot. My father’s first visit was very painful. He and I barely fought back our tears. Mostly because we were on opposite sides of prison bars, he on the outside, I on the inside. The next visit was already easier. A person gets used to that as well.

I was in solitary a little more than three months, up until the indictment was filed. Later, for another ten days, but this time as punishment. As a woman I had the privilege to walk alone in the prison yard. I was, namely, the only woman in solitary, in a line of solitary cells spanning a long hallway. I consider this a privilege as well. It would have been much more difficult for me had I been forced to hold my hands behind my back and someone followed me during my walks. Neither in solitary nor later, in a group cell, was I ever hit. A guard who had beaten a prisoner in the solitary cell next to mine because he had made his “bed” before it was time hadn’t even waved his baton at me. That wasn’t because I was a woman. In the group room I saw a woman who was “blue” from a beating. In my opinion, prison guards and supervisors were ordered not to beat “political” prisoners. There was shouting, threats of violence, but never physical assault. Of course, I am describing my thoughts and my experience.

From the arrest to the indictment – that is, while I was in solitary – the investigating judge and prosecutor, like the DB officers before them, were most interested in where the books and journals taken during the search came from. I understood, with reason I think, that that question was supposed to lead to a further “investigative narrative.” But, it seemed like at that point that they didn’t have any other charge against me other than the books.

In the decision to initiate the investigation for “proof” of my “enemy association and enemy propaganda,” the confiscated books, brochures, journals and leaflets were deemed Trotskyist, with or without quotes… In a grievance against the decision, I noted that some of those texts qualified as Trotskyist were in fact anti-Trotskyist. That was the way they qualified one shorter text titled “The Truth About Kronstadt,” a text I translated, and in which Trotsky, because of his role in the suppression of the uprising, is called, among other things, a murderer. Also, that was how one book, actually a collection of Russian authors titled “Anarchism, Trotskyism, and Maoism,” which was translated to Serbo-Croatian around the end of the 60s was labeled. I even insisted on this during my first interrogation. The judge and the prosecutor looked at me “obtusely.” It appears that by the time the indictment was brought against me I had managed to “convince” them that this other book was not Trotskyist. It wasn’t mentioned in the charges nor the trial. But they did not give up on “The Truth About Kronstadt.” Maybe because it would be very “convenient if that text were Trotskyist” – both because I had translated it, and because it was found during the searches on multiple occasions. The prosecutor’s questions about where this or that book came from were aggressively pointed. My answer that having books is not an enemy act was replied with the insistence that the possession of enemy works is a hostile act, and that only a person who knows they are guilty would avoid answering such questions. In the moment, instinctively, I accepted his terminology and his “advice” and told him I would tell him where the books came from, if he could prove they were “hostile.” (It’s a good thing I didn’t have the Mein Kampf.) The prosecutor hurried, with nervous movements looking for something “hostile.” He snatched up some bulletin and told me “here, look, this is illegal.” Whether the word “illegal” was used in the bulletin or not, I don’t know. To my answer that illegal does not mean “hostile” as, I said, the KPJ was also illegal before the war, the prosecutor, the infamous Stojan Miletić, first went red in the face and stumbled on his words, and then, literally, jumped up and actually ran out of the courtroom into the hallway. Neither my lawyer, nor even the judge, could hide their snickering. I looked at the judge in astonishment. I wasn’t scared of him anymore. S. Miletić was a small Vyshinsky, without the authority Vyshinsky had.[8] To the questions about literature, asked in a variety of ways during several interrogations, I answered roughly the same, leaning on the fact that books have nothing to do with the criminal charges against me.

Why was I that “hardheaded”? Between everything else, it was the fact that I couldn’t give any, by my understanding, logical response without providing another person’s name. I would have said that I purchased the books at a bookstore, but I knew they would easily “catch me in a lie.” Actually, I could have done it that way and then made them prove that I didn’t. But, plainly, I didn’t think of that. Along with the questions about the literature, they also asked me about Milan’s text (I wasn’t told that it was Milan’s) which was signed “IG RRP.” But, they didn’t push that. I told them I was seeing the text for the first time. It was my right to lie during the investigatory proceedings. The second lie regarded the question of my attendance at a large international conference, primarily of Eastern European dissidents, in Essen, at the beginning of June 1971. I think the investigative judge “read” me, but he couldn’t prove that I was there. With that, the investigative proceedings were primarily completed. In sum, I think, 4-5 interrogations, and maybe even less. There was no confrontation with the accused in the “group.” A charge followed which was an extended and systematic version of the resolution to move forward the investigation. I wasn’t too excited about it. I was more worried that they, that is to say, immediately after the indictment, moved me to a group cell. While I read the indictment I felt, for the nth time, as though I was “thrown into” some sort of theater of the absurd.[9]

In the group cell there is light, the bathroom is closed. The beds have some sort of mattresses. But, I wasn’t worried about “comfort,” but because of the other prisoners. In the room there were usually 10-15 women. Never before that had I had close contact with people who were charged or convicted as “ordinary” criminals. Everything I had read thus far from the mass of prison literature, of the relations between “criminal” and “political” prisoners, told me I was safer in solitary than I was in a group room. And the other prisoners didn’t, at first sight, give me much confidence. I liked only Zelenika, who at the door told me that I was “certainly not the type who stole, nor whored, nor killed,” and thus I must be “a student.” She figured that out, of course, from the books. Quickly I realized that for years she had begged in the Student City [a block of student dormitories in Belgrade]. I remembered her charming way of asking for money, right before the break, when she’d holler at the students “colleagues, should we go to mathematics.” She was delighted when I remembered that. “The ice” was broken. The other prisoners looked at me like an “oddity,” but not in an unfriendly way. Within a day or two, more or less, they all told me their stories. At least half of the prisoners, who I met over those 6-7 months, didn’t even need to be in prison. “My” Zelenika ended up in prison because she was taking money for “palm reading.” Another, also an older woman, because she stole 200 grams of coffee from a store. That poor woman barely walked – she had advanced tuberculosis. Some women were involved in prostitution, and along the way in pickpocketing, at the štajg [sl. train station]. Even if I was a sociologist by training, that was the first time I heard the term “štajg.”

There were of course also women charged with more serious crimes. I was most afraid of Silvija, who was accused of killing an old woman. It turned out that Silvija and I would become the “soul” of the transformation of the group of prisoners in “our” cell into some sort of strange, even comfortable, prisoner “community.” There were conflicts and arguments, but without serious consequences. I taught Silvija to read and write. She fell in love with Larkin’s poetry. On other nights, at lights off, the women carefully listened to my quiet recitations of the poems of D. Maksimović, Larkin, Neruda… Silvija told, in an interesting and juicy folk dialect, “horror stories.” For New Year’s 1973, we sang songs like “Ščepaj ga, ne daj ga, jer je muškarac” [“Grab him, don’t give him away, because he is a man”], the prisoners “hymn,” “Na Sing Singu zastava se vije” [“At Sing Sing the flag is flying”], and, by my request, the Internationale. In the moment while we sang the Internationale one haughty guard who usually “couldn’t stand to see me with his own eyes” flew into the room. Who knows why the singing of this international workers’ “hymn” specifically irritated him. He hit the first woman he “ran into” with his nightstick. I stood between them. He yelled, threatening that I will “meet my maker” when the final verdict is given, but he didn’t hit me. Not because I was some sort of “force,” but, as I said earlier, because he wasn’t allowed to. He managed to shut down our prisoner New Year’s “celebration.” But, not one woman judged me for our singing of the Internationale. We all condemned the guard. There, that’s what our prison community was like. [10]

The Trial

The trial began at the beginning of July. Maybe it sounds pathetic, but I felt “super.” The monotony of prison days was interrupted. I saw my accused comrades. Finally I could normally hug and kiss my father and sister. In some waiting room, some girlfriends managed to approach me. In the courtroom there were many familiar and cherished faces. From the perspective of the accused, only the attendance of such people at a trial means so much. That means that even in “freedom” there is still resistance, which is experienced as a concrete solidarity, as a sign of support and encouragement, at least in the terms of condemning the perpetrators of repression.[11] The presiding judge in our processing, within the five-member panel of judges, was Milivoje Đokić. The prosecutor, as is usually the rule in court proceedings, remained the same. M. Nikolić, the first to be charged, was defended by the most famous lawyer for “political delicts” in Belgrade, Srđa Popović. Imširović’s defense was a distinguished old Belgrade lawyer, Savo Strugar. There was also my lawyer, Vitomir Knežević. As the third defendant, as court procedure required, I was “neglected” for a full two days. In the beginning of the process, I sat at the defendants’ bench for a very short period of time. From the third day, I was a permanent member of the “group” on the defendants’ bench. For two days, my father carefully followed the proceedings, yet my name was unmentioned. At the end of the second day of the trial, he intercepted the prosecutor in the hall and asked him why I was indicted at all, when no one is charging me for anything. S. Miletić snapped at my father that I am “actually the most dangerous, since I “destroyed evidence.” The prosecutor was in “his element” during the whole trial. He threatened Imširović at least 5-6 times with new charges. He responded the same to his closing defense. That was at least to be expected from this eager state prosecutor. But, in that moment, S. Miletić “reversed” on himself: he accused that, all three of us, were, no more, no less, tied to Jelić’s Ustaše. I cannot tell remember what “inspired” him to make such a proclamation, but the memory of that accusation stayed with me for a long time. For a some seconds, literally, I was left breathless. My lawyer broke the silence. The prosecutor didn’t give a chance to “get through to him.” He yelled at V. Knežević, using the informal “you” and calling him “Vanda” (Vanda was at that time a popular Bulgarian sibyl).[12] It wasn’t easy for the presiding judge. But, I wasn’t very concerned about him at the time. I only registered that he was more unbiased than the investigative judge.

For me personally the most painful moment during the trial was when one of my students arrived in the courtroom as a witness to the prosecution. He was the only witness in the whole procedure against “dangerous enemy groups.” For some months, mainly because of money, while waiting for my University stipend, I worked in the Center for Professional Training of Workers PK “Beograd.” At one lecture, after Milan and Pavluško’s arrest, as it was ascertained in the trial, “I spoke of social inequality, and gave one concerned student a flyer about that, and invited other students to meetings and talks at the Faculty of Philosophy.” The poor student gave his testimony in absolutely bureaucratic jargon. He said the words “enemy propaganda,” “inviting,” and “flyer”… When he relaxed and began to speak with his own words, the impressions one could gather about my lectures were quite different. My reconstruction of the lectures I gave 6-7 months ago was more complete, it is understood, than the student’s. But who was even interested in that in this surreal atmosphere of criminal proceedings? So that there is no confusion, I did mention at the end of a class, which I always thought of and conceptualized as a dialogue, that the students in the ’68 protests were against social inequality, that that problem was one of the key themes around which students debated in their assemblies, tribunes, and which was written about in the student press. But, I did not invite students to come to any meetings. I did cite statistics from one text about social inequality, which was distributed at one of many student assemblies. I did give one copy of this text to just one interested student. And that was all. To say only one more thing, that that “flyer” contained primarily statistical indicators about social inequality in our society. If I had known that one of my students would be mistreated by DB officers because of my lecture, I probably would have “skipped” the whole lecture about social structures and class hierarchies. In the context of the key thesis of the indictment, that we were, the accused, an enemy Trotskyist group, my student’s statement played a completely secondary role. Before the trial, the investigation, obviously, had problems with not only “placing me in the group,” but with proving that I was working with “enemy propaganda.” The testimony of my student was one of the “more convincing” secondary evidence for hostile activity of the accused. The other “evidence” of a similar form and function were sentences, and often just words, from private letters, primarily Milan’s, addressed to his girlfriend. The verdicts for the trial were – Milan’s statement that he wrote the text under which was signed IG RRP and that he only showed it to Pavluško (who denied this), and that the margin notes of that text an expert determined were mine (which I did not admit to at the trial). And there, the case was, more or less, “closed.”

Twenty-first of July, 1972. The District Court of Belgrade issued a verdict stating that the accused committed the criminal offense of associating against the people and state from Article 117, Paragraph 1, in conjunction with KZ [criminal law] Article 100. Milan Nikolić and Pavluško Imširović were sentenced each to two years of harsh prison [a category of prison in Yugoslavia, “strogi zatvor”], and I, Jelka Kljajić, was sentenced to one and a half years of harsh prison. In the verdict there wasn’t, as in the indictment, an addition of enemy propaganda charges. In the charge of “enemy association,” the group was not characterized as Trotskyist, but only as enemy. In the reasoning of the verdict, among other things, Trotsky, Trotskyists and Trotskyism were mentioned, but the convicted three [Troika] were not qualified as Trotskyist.

I didn’t feel the sentences were long. Only in one moment, during the sentencing in the courtroom, when it appeared to me that the judge said Pavluško was sentenced to five years of harsh prison, I felt “stunned.” I stayed quiet when the judge asked me if I understood the verdict. Why didn’t I find the verdict horrific? Because I had thought that, in the social climate as it was, that the punishments would be even harsher. And not only because of that. For the crime of associating against the people and state the minimum sentence was five years of harsh prison. Both in the resolution to initiate an investigation, and in the response to my complaint regarding my detention, it was emphasized that is the minimal possible sentence, either as a statement in relation to one of the offenses attributed to me, or worse yet, as a key reason as to why I could not be allowed to defend myself outside of the prison during the trial. I did not regard myself nor my friends as mere victims of a repressive regime. I assumed that a person who in any way opposes such a regime should take into account that with that there is a high likelihood that they will be convicted. That is understood, if the regime is not changed. In the first ten days in solitary, I “pieced out” a sentence of 5 years for myself, and for my friends, 1 or 2 years more. I didn’t even hope that those who arrested us would give up the charges, and it didn’t occur to me that the judge can announce a sentence below the legal mandatory minimum. When my lawyer told me that the legal minimum sentence for specific crimes cannot be, by law, decided before the sentencing, I did not believe him. Not because I didn’t have faith in him, but because I was convinced that he was only trying to comfort me. Even today I don’t understand the logic of pronouncing a punishment under the written mandatory minimum. When I thought not from the perspective of the repressive judicial regime, but from the perspective of what I actually did and how much what I did was actually dangerous to the regime, the punishment looked exceptionally high to me. In solitary my thoughts frequently “screamed” about why I didn’t at least write something the regime would have deemed subversive. When, after leaving prison, I found the “case” of Lazar Stojanović, that is, the fact that he was convicted for his film “Plastični Isus” [“Plastic Jesus”], I “envied” him.

Even if we didn’t “emerge” as the Trotskyist Troika [three] in the verdict, we were still that in the regime’s media. Just like the arrest and the trial, that too was by political orders. I don’t think that was some form of direct orders in terms of “you have to write this and that,” but authors have similarly unmistakably felt how one has to write about trials and convicts.

(…)

While I was in prison, in the period between the announcement of the verdict and the wait for the final sentencing, i.e. the sentence of the Supreme Court of Serbia, in October 1972, certain Party liberals were removed from political party roles. Others, sooner or later, resigned. I can’t say that I felt for them, but I did not rejoice in this inter-party conflict. From my personal point of view, they were primarily executors of Broz’s political orders. Inter-party differences obviously existed, but the “dirty” work, i.e. repressive measures against activists and social critics after the student protests of ’68, all up until their fall from power, was carried out by liberals. I knew, that is, assumed, that after the expulsions of “liberals” it would be even worse. That was not hard to assume. Everyone who even barely followed what was happening in the political scene knew that behind all repressive measures stood a factually conservative party leadership headed by J. Broz.[13]

Translator Notes:

The terms “enemy” and “hostile” were translated from the Serbo-Croatian word neprijateljsko, which translates very literally to “unfriendly”. Within the socialist period, this term somewhat connotes “against the people.”

The term Praxis-ists comes from the author’s use of “Praksisovci.” It may be also said as “Praxis theorists” or “those involved with or using the theories of the Praxis school.”

The term “Troika” (Trojka in Serbo-Croatian) is sometimes used as a noun, but is a reference to “three of something,” usually a group of three political organizers, and here referencing the three charged dissidents.

“Harsh prison” is translated from the Serbo-Croatian term “strogi zatvor.” “Strogi zatvor” is meant for those serving 1 to 15 years in prison, under harsher conditions, for “more serious crimes”.

Jelka Kljajić Imširović (1947-2006), sociologist, member of the Belgrade radical ’68 circle, she called herself an anarchist sometimes, although her major influence was Rosa Luxemburg. She was a feminist and an anti-war activist. Author of the book: Od staljininizma do samoupravnog nacionalizma (From Stalinism to self-managed nationalism, Belgrade, 1991)

[1] In the 1968 student rebellions across the world, and for years after that, Che Guevara was the idol of revolutionaries, perhaps for many the biggest. In contrast to Western nations, neither Mao Zedong nor Castro were not revolutionary idols in Yugoslavia.

[2] I specifically thought of, before all else, some beliefs of professor Lj. Tadić about humanistic intellect and social critique as the substitute for progressive social movements in societies where the proletarian vanguard became the conservative political elite, and where the workers’ movement lost the vitality of being a historical subject.

[3] My presentation at the Korčula summer school, titled Contribution to the critique of the Yugoslav Praxis philosophy, in written form, in Serbo-Croatian and in German, ended up in the SDB [State Security Agency] archives. The text was taken from me, along with many other things, during the arrest. I reconstructed my critiques from then using notes about the Praxis philosophy which were the backbone of my presentation at an Open University session (which, as far as I remember, happened in 1977). At the Korčula school and directly after that, reactions to mine and Milan’s presentations were varied. I will describe, without comment, some reactions. Rudi Supek, directly after our presentations, in the “official” part of the program, qualified our statements as inappropriate, unnecessary, and Stalinist in essence. Gajo Petrović, I can’t remember whether the same day or the next day, evaluated our statements as a plea to dialogue regarding the open questions within critical Marxist theory and praxis. Outside of the “official” program of the Korčula school, Lj. Tadić had a distinctively negative response to, before all else, my presentation. In one smaller circle, that is a social circle, he said that the consequence of my insistence on concrete criticism of Yugoslav society reduces critical thought to action pamphlets and slogans. He learned on, at the same time, Adorno’s responses to the rebelling students from the Free University of Berlin. His second objection (which really frustrated me) was that my and Milan’s critiques were used by the authorities for yet another attack on the Praxis school. I’m pretty sure that I remember the name of the man who wrote a text for Politika which pretty much said that students attacked the Praxis professors in Korčula. But, I’m not completely sure I remember and thus I won’t mention that then-young man’s name. The majority of reactions were positive, either in the sense of agreement with some statements, or, more frequently, in the sense which G. Petrović spoke. The majority of my professors, the Belgrade Praxis-ists, thought that the conversation should continue in the Faculty of Philosophy associations, tribunes, etc.

[4] Politicians and party intellectuals avoided speaking about the strikes, which they usually, when they really did not have a way to get out of saying something about them, called work interruptions.

[5] Milan showed me his text somewhere around fall 1971. I “scolded” him (I wasn’t the only one) for “strolling” around the city with it, but I read the text and in the margins wrote (I tried to, advertently, “switch up” my handwriting) remarks and reminders in short, crude form, at times in the form of only a question mark. Some remarks were of an essential character. At that time I had already decided, i.e. broke it somehow within myself, that the formation of a revolutionary party were necessary. Some reservations persisted, and I still didn’t know how, but – the decision was there.

[6]Even today this doesn’t make sense to me. It’s possible that the narrative about the three was supposed to be the potential for a “deep illegal and conspiratorial character of our Trotskyists,” i.e to frame them in the public eye as dangerous as possible. It’s possible that those days’ prosecutors were repeating some earlier (prewar) models of attack on Trotskyists or “Trotskyists.” Maybe it was a self-projection, i.e. the attribution to “Trotskyism” of some forms of illegal activities of the prewar KPJ… But, it’s possible that the leaders of the attacks on Trotskyism had in mind a fact, based on the intelligence of the SDB, that for the majority of people the charge of “enemy Trotskyist association” was difficult to “prove” in any believable way. And, I suppose, it must have been clear to them that the time of “Dachau show trials,” for example, was a thing of the past. In support of this interpretation is the fact that the authorities failed, though they tried, to remove the second “Trotskyist Troika.”

[7]I openly told two of my colleagues from the sociology department, Marko Vuković and Duško Stupar, that I thought they were working with DB. After that, the socializing stopped. Duško Stupar “climbed up” to the position of Deputy Minister of Serbia’s Ministry of Interior. He left that position because of “some indiscretions,” allegedly giving some “confidential material” to Dragiša-Buci Pavlović during the time of the famous 8th Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Serbia [CK SKS]. Today he’s, as far as I know, a businessman in Russia. Both, I can say with calm conscience, profited from the student protest in ’68. I helped both of them prepare for exams until I “opened my eyes.” Marko swore to me in every way, on multiple occasions during chance encounters, as he did the first time I “attacked” him, that he did not work for SDB. Stupar exposed him to me at the beginning of the 80s. And the Deputy Minister of the Interior of Serbia gave me his honorable word that there was nothing more to my arrest. Perhaps they really had no “connection” to my arrest, but their role, greater or lesser, in the repression that followed the student protests was undeniable.

[8] Stojan Miletić, after our trial, was promoted to the position of deputy public prosecutor of the Republic.

[9] The only thing related to the indictment that hit me was one article in NIN [Nedeljne informativne novine; “Weekly Informational Newspaper”] titled “the Secrets of Our Trotskyists.” I’m not sure which journalist wrote it. I can’t find him in my small “prison documentation.” But, I still remember that the “Trotskyist Troika” was blatantly accused of “planning urban guerilla warfare.” All of that was based on one book on the topic found in Milan’s apartment during the search.

[10] One political prisoner, Ljubica Živković, told me, based on her experience in Požarevac prison that she had problems with “criminals.” I am unsure how I would have gotten by in a huge space with 50-60 women just in the sleeping quarters. I probably would have felt like a “lost cause.”

[11]One consequence of a system of selective repression, and even mass repression, is that people directly attacked by repressive measures are never left without some kind of support. I am sure that for us, and not only for us, the sentence would have been far harsher had the courtroom been empty or, as it happened at the end of the 40s through the 50s, “filled” with plain clothes police officers.

[12]From this work it’s evident that I am somehow “fascinated” by the prosecutor. I have already written some sociological remarks related to this type of character and role-playing. If I had literary talents, S. Miletić would be one of the key figures in my prison drama of the absurd. In relation to my prosecutor I’ll mention only one more detail. When a friend of mine and I, at least 6-7 months after my release from prison, yelled “Booo, prosecutor!” he followed us through the streets of the Old Town for at least one hundred meters.

[13] I didn’t expect that the ousted liberals would become the opposition. Barely anyone expected that of them. After Đilas, barely anyone from the head of the party became a dissident. As far as I know, only D. Ćosić. Not even A. Ranković, nor Slavka Dabčević-Kučar, nor Luka Tripalo became that. Nor M. Nikezić, L. Perović, K. Popović…