Black & Red correspondents (November, 1968)

Alert readers of the Western press may have noted short accounts of a “student rebellion” during the first half of the month of June in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Beyond a few journalistic expressions of admiration for Tito’s handling of students, the press has been left dumb by the events; after all, one might expect a student revolt in Poland or Czechoslovakia, but in liberal Yugoslavia? As yet there exists no analysis of the events of June nor of their impact on Yugoslav society. In order to provide precisely such an analysis, let us begin by recounting what actually happened in Belgrade.

Chronology Of Events

The Explosion

A troop of actors was scheduled to perform free of charge on the second of June before an audience of “Youth-Action” workers camped nearby a large complex of student dormitories located in New Belgrade, a suburb of Belgrade. Student representatives had requested that the performance be held in a large open amphitheater so that those other than members of the Youth-Action could attend. Announcing that such free cultural events were the privilege of the Youth-Action only, the authorities scheduled the performance for a small theater. Angered by this, several students attempted to force their way into the theater before the performance, but after a short struggle were expelled by the police. News of the expulsion flashed through the student village and soon a crowd of over a thousand students gathered in front of the theater. -After only a few minutes of hesitation the crowd attacked the theater, breaking windows, ripping off the doors and fighting with those already inside.

Police reinforcements arrived quickly with a fire truck, but before they could use the hoses, the students captured and burned it. With this, the police attacked. The students responded with barricades made of overturned automobiles and stones. After several violent clashes the students retreated to their dormitory village to discuss further action.

March on Belgrade

Discussions lasting through the night produced a plan: the students would march the next morning in mass to a central square in downtown Belgrade. There they would place before the public the following demands: the immediate release of all students arrested in the previous day’s riot, the resignation of the chief of police, and the withdrawal of all the police from the student village in New Belgrade.

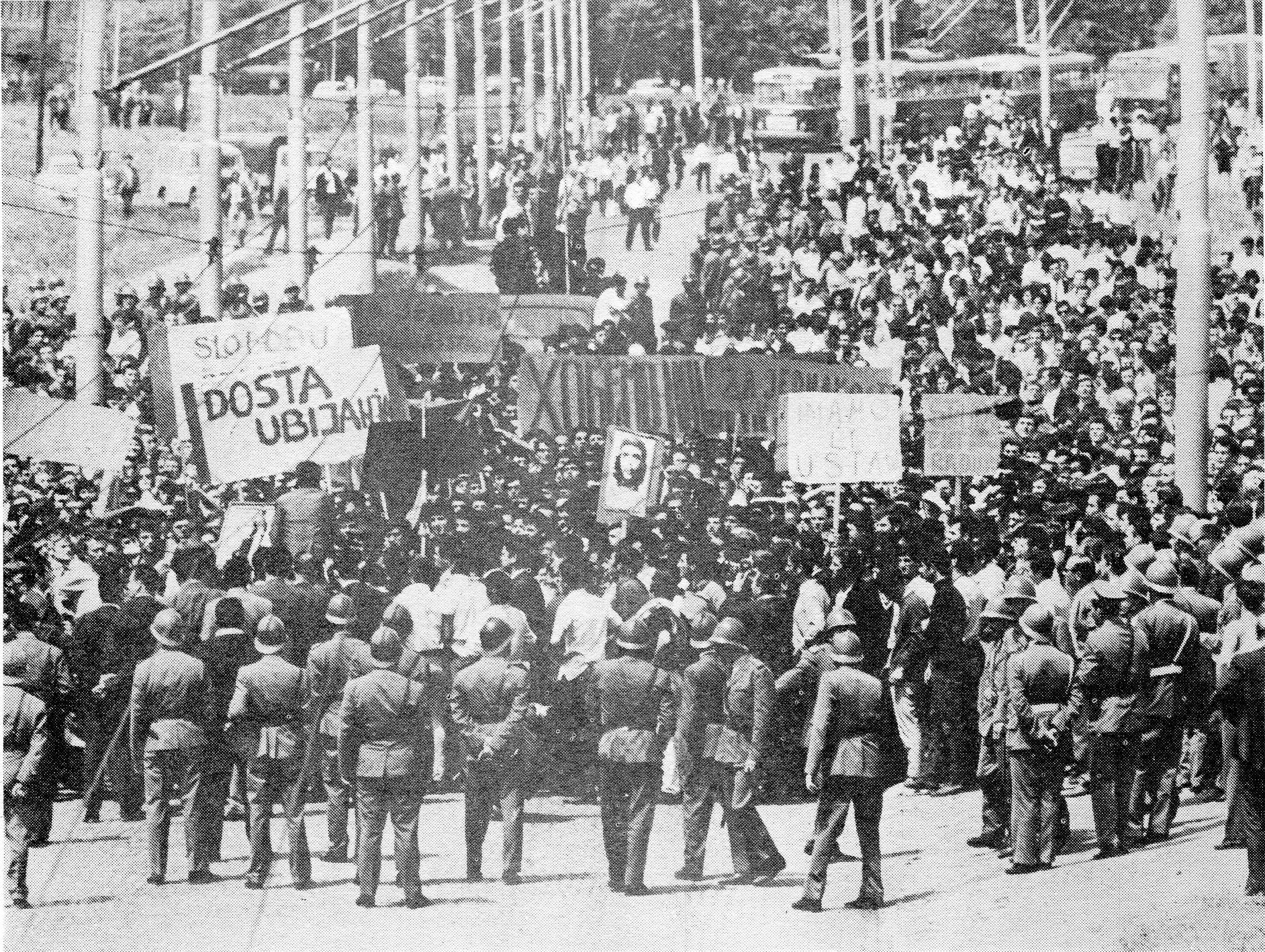

On the morning of June third, three to four thousand students formed and began the ten kilometer march to downtown Belgrade. Approximately midway, they were met by a blockade of thousands of police gathered from all over the state of Serbia. As they neared the blockade, the President of the Parliament of Serbia and the President of the League of Communists stepped forward and invited the students to negotiate. But without warning, soon after negotiations had begun, the police opened fire with their pistols and charged the students. In the violent battle that ensued, 60 to 70 people were wounded, including the two government authorities who had attempted to negotiate with the students.

Mass Meeting

That afternoon, ten thousand students met in New Belgrade and decided to form an “Action Committee” to achieve their demands. While this meeting was going on, in downtown Belgrade a group of several hundred students occupied the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty of the University of Belgrade. Later that afternoon, groups of students distributed, in the streets and cafes, leaflets seeking:

(1) The rapid solution of the employment problem facing new university graduates, most of whom must go abroad if they want to find any sort of employment;

(2) The suppression of the great inequalities in Yugoslavia;

(3) The establishment of real democracy and self-management relations;

(4) The immediate release of all arrested students;

(5) The resignation of the chief of police;

(6) Convening the Parliament to discuss the demands of students;

(7) The resignation of the directors of all Belgrade newspapers, radio, and T.V. for having deliberately falsified the events of the 2nd of June.

On the evening of the 3rd of June, thousands of students in Nis, a large industrial center in Serbia, marched in the streets to demonstrate their solidarity with the students of Belgrade.

Occupation of the Faculties

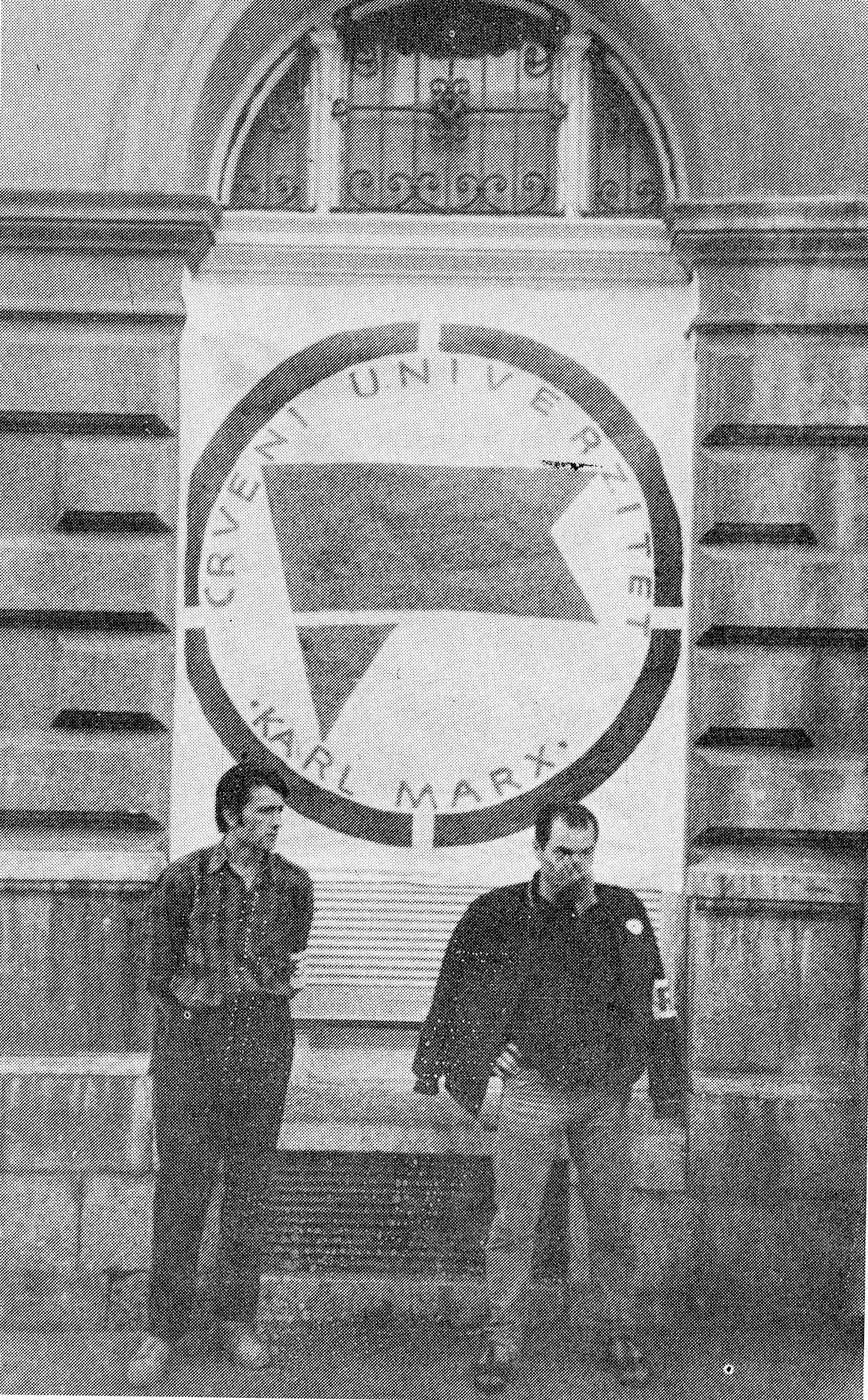

As mentioned before, the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty was occupied on the afternoon of June 3rd. It was there that the organizational forms, the general assembly of all the students and professors, and functional action committees were born. The occupations of other faculties were organized at the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty. With a high degree of inter-faculty coordination, students established committees for the elaboration of their demands, for political agitation and Propaganda, and for the construction of student-worker unity. It was not long before the facades of the buildings were covered with posters carrying such slogans as: “students, workers and peasants unite against the bureaucrats,” “tomorrow without those who sold yesterday,” “down with the red bourgeoisie,” “show a bureaucrat that he is incapable and he will quickly show you what he is capable of,” “more schools, less autos,” and “brotherhood and equality for all the people in Yugoslavia.”

Isolation of the Movement

But as the students organized, the state began to act. At a special meeting of the City Committee of the League of Communists, the Mayor of Belgrade warned, “the enemy is active these days in Belgrade…we cannot allow demonstrations against our system.” The meeting decided to take three actions. First, it filled the streets with steel-helmeted riot police under orders to prevent demonstrations. Second, it called on all Communist League cells in all stores, institutes and factories to prevent all contact between students and workers. Third, League cells in factories were instructed to organize armed workers’ militias to prevent students from destroying social property. Thus, by the evening of June 4th, the League of Communists had tightened its grip and effectively isolated the “enemy” from the rest of society.

On the 5th of June, the second day of faculty occupations, the police began to encircle the faculty buildings. By mid-day it became obvious to all that the police were mobilizing for attack. Borba, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Socialist Alliance justified the attack in advance by printing, “If we would like our self-management democracy to develop normally, we must protect it by all means available against those who would impose their will by means of disorder in the street.”

As if to dishearten the students, letters from workers’ councils in factories in and around Belgrade began to flow in. Following the same formula, all the letters expressed complete faith in the leaders of Yugoslavia and attacked the students for their selfish impatience and for destruction of social property.

From the first day of the occupation certain professors, particularly those of the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty, joined the students. Other than these few professors, only groups of writers and artists made public their support of the student movement. But by mid-day of the 5th, many professors began to return to the faculties. These late-comers, most of whom were high ranking party officials, government ministers, economic, scientific or technical consultants as well as professors, warned the students of their total isolation, and advised that with the aid of the professors, the students would gain all their demands by means of existing party channels.

On the evening of June 5th, it was learned that Sarajevo students manifesting their solidarity with Belgrade students had been brutally attacked by the police.

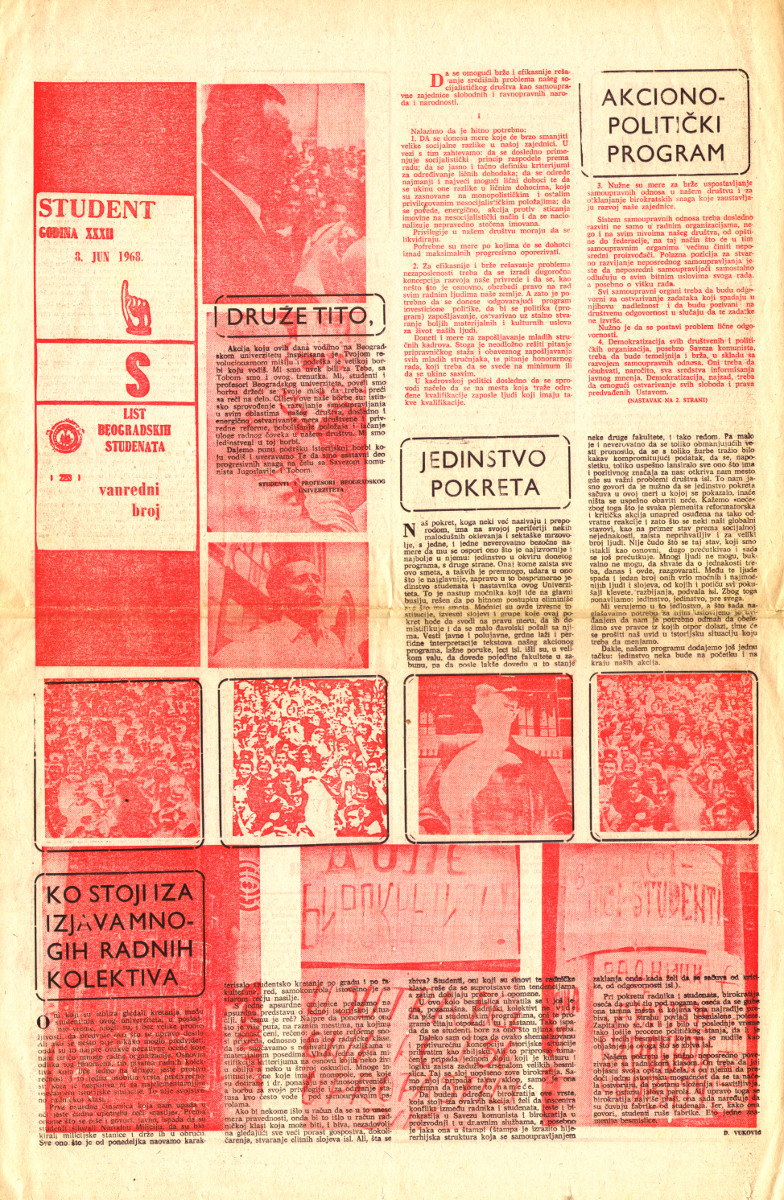

Early on the morning of June 6th, the students decided to take the advice of the late-coming professors, and to frame a summary list of demands to be presented to the University Committee of the League of Communists. As printed in Student, the official student newspaper, the demands were as follows:

Political Action Program

“In order to make possible the most rapid and effective solution to the major problems facing our socialist society and our self-managed community of free and equal people and nations, we find the following to be necessary:

I.

(1) To adopt measures which will quickly reduce the great social differences in our community. In connection with this we require: that the socialist principle of distribution according to work be systematically applied; that criteria for determining personal income be clearly and exactly established; that a minimum and maximum personal income be determined; abolition of those differences in personal income based on monopolistic or other privileged non-socialist positions, action against the accumulation of private property in a non-socialist manner, and immediate nationalization of improperly-gained private property. Privilege in our society must be liquidated. Measures are necessary to progressively tax incomes above the determined maximum.

(2) In order to make possible rapid and effective solution to the problem of unemployment, a long-range development concept of our economy must be adopted, based on the right to work for all people in our country. Following this, it is necessary to adopt a corresponding investment policy in order that full employment be created along with improved material and cultural conditions for all our people. Measures must be taken to make possible the employment of young qualified workers. Honorary and overtime work must be reduced to a minimum or prohibited altogether. Unfilled work-places must be filled only by those possessing the necessary qualifications.

(3) Measures are required for the rapid creation of self-management relations in our society and for the destruction of those bureaucratic forces which have hampered the development of our community. Self-management relations must be systematically developed not only in working to organize unions but also at all levels of our society, communal and federal, in such a way as to make possible real control by producers over these organs. The essential point in the development of real self-management is that workers independently decide on all important conditions of work and on the distribution of their surplus value.

All self-management organs must be responsible for the completion of their particular tasks and must be held socially responsible in case they fail to complete these tasks. Personal responsibility must be given its full importance.

(4) Together with the development of self-management organs, all social and political organizations–in particular the League of Communists–must adopt democratic internal reforms. Most importantly, a basic democratization of the means of public communication must be carried out. Finally, the democratization must make possible the realization of all freedoms and rights foreseen in the Constitution.

(5) Decisively stop all attempts to disintegrate or turn social property into the property of stockholders. Energetically stop all attempts to turn private labor into the capital of individuals or groups. Both of these tendencies must be clearly made illegal by appropriate laws.

(6) The housing law must be amended immediately to prevent speculation on social and private property.

(7) Cultural relations must be such that commercialization is rendered impossible and that conditions are created so that cultural and creative facilities are open to all.

II.

(1) The educational system must be immediately reformed so as to answer the needs of development of economic, cultural and self-management relations.

(2) To adopt a constitutional guarantee for the right of all young people to equal education conditions.

(3) To write into law the autonomy of the University.”

Rejection of Compromise

When the University Committee of the Communist League received the students’ Action Program, it expressed its solidarity with the student movement and began negotiations with the City Committee.

On June 6th, the students addressed the following open letter to the workers of Yugoslavia:

“We do not fight for our own material interests. We are enraged by the enormous social and economic differences in society. We do not want the working class to be sacrificed for the sake of reforms. We are for self-management, but against the enrichment of those who depend on and control the working class. We will not permit workers and students to be divided and turned one against the other. Your interests and our interests are the same, ours are the real interests of socialism.”

That evening several hundred workers attended the General Assembly at the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty and many spoke to an enthusiastic audience of students, workers and peasants. At that meeting it was learned that the newspaper Student had been seized by the state.

As negotiations between the University and City Committees of the Communist League were nearing a compromise agreement, the argument that the students had lost control of their movement by allowing themselves to be represented by the University Committee began to win majority support among the students. Thus, on the following day when the University Committee presented the compromise agreement it had reached with the City Committee, the students promptly rejected it.

The Crisis and Tito’s Solution

On June 9th, events reached crisis proportions. All the newspapers were screaming for stern punishment of the rebellious students. The police closed in on the faculties and cut off all entry. A police unit stationed at the Faculty of Art entered the building and beat and arrested many students. That evening it was announced that the President of Yugoslavia would address the nation on the following day.

President Tito surprised the nation by supporting the students’ Action Program. He found it to be a challenge for Yugoslav communists to turn words into deeds. Yes, he knew that there were extremists among the students and he also felt that he must condemn their use of violence. He praised, however, the new political consciousness of the students and declared it to be the fruit of socialist self-management relations. He called on all communists to make a reality of the students’ program. Finally, he added that if he could not engineer the realization of their program he should resign from his position as head of state.

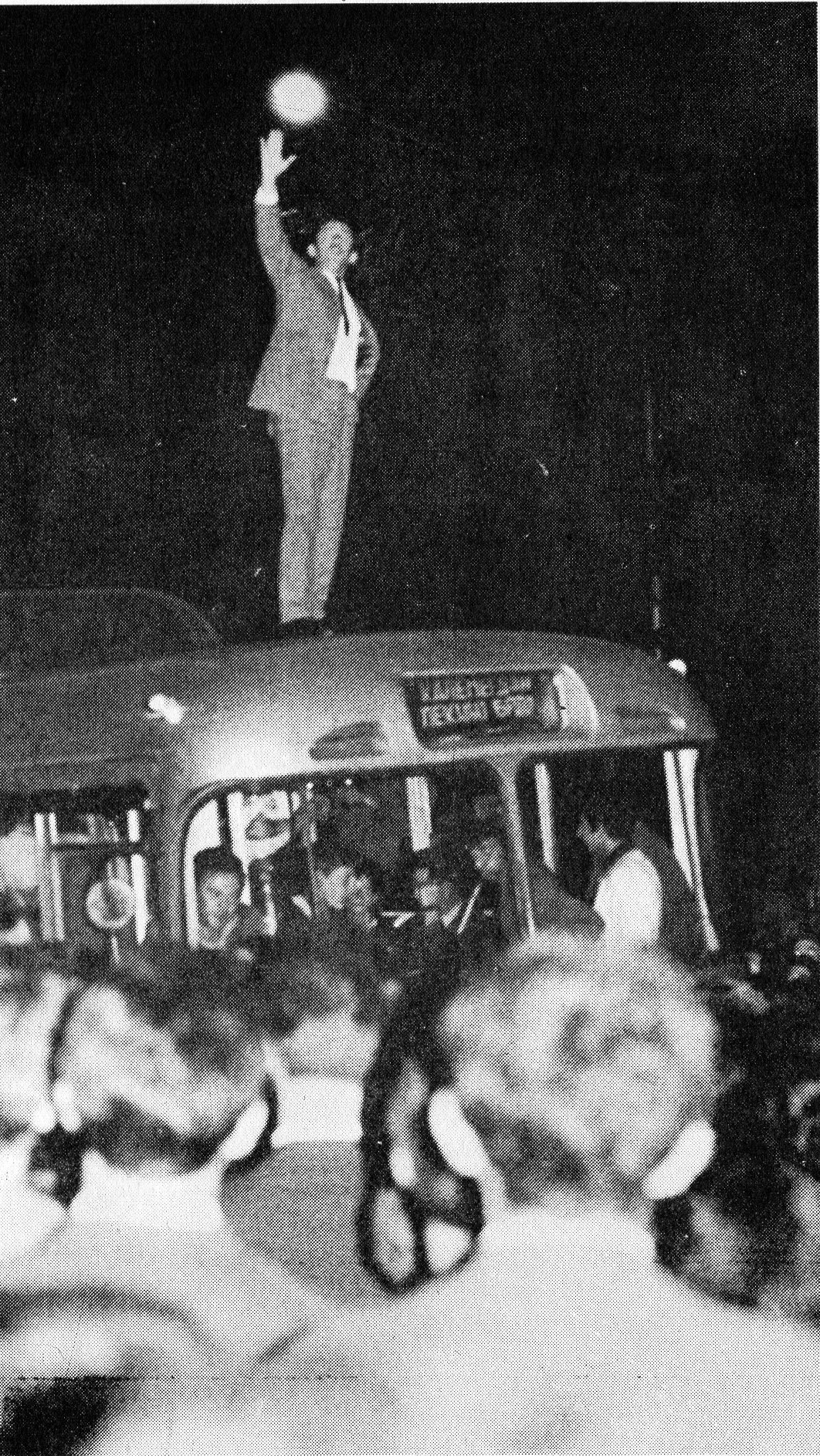

Learning of Tito’s support of their program, the students stormed out of their faculties and paraded in the streets of Belgrade. The police were nowhere to be seen. The evening papers announced that they had misinterpreted the students’ program and, after reconsidering it, found that they must agree with Comrade Tito. Suddenly, the students found that their movement had achieved a semi-legal status.

Revolutionary program

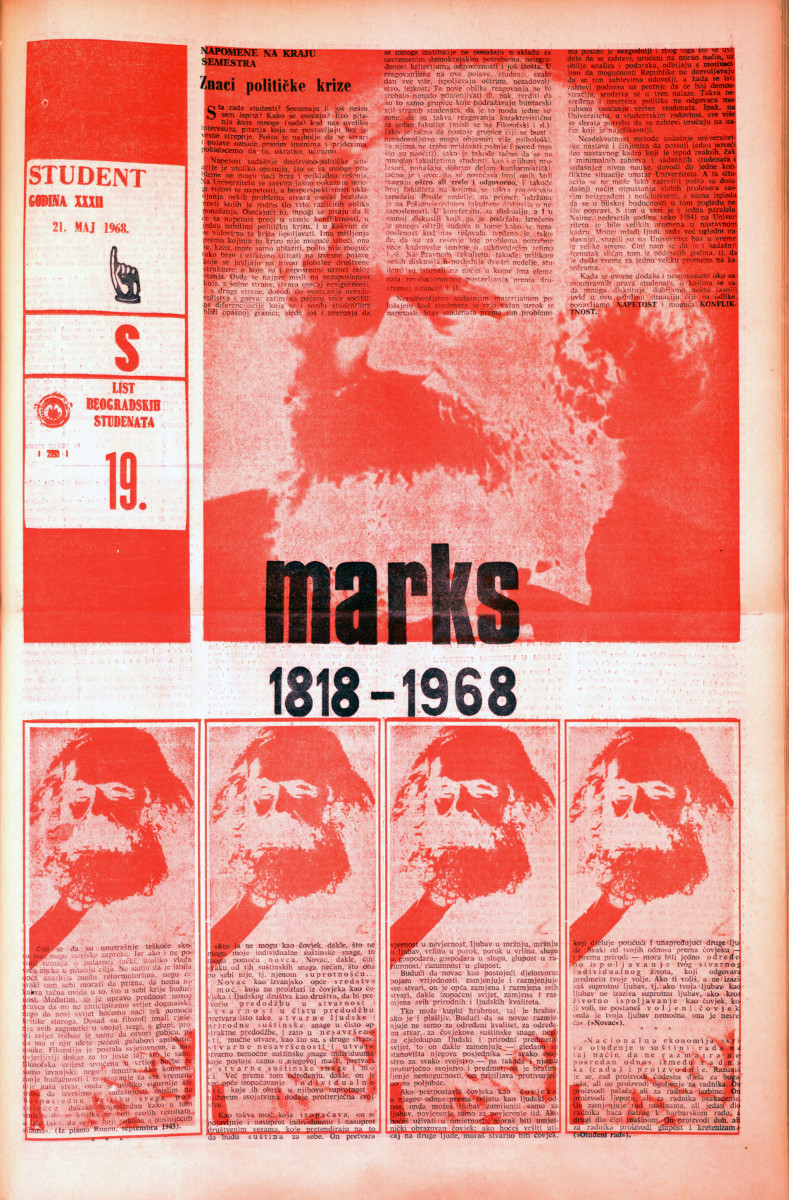

The immediate fruit of Tito’s support was to de-activate the mass movement. Now, they were told, they had done their bit and should concentrate on problems within the university. In most faculties these instructions were, in fact, followed–the exception being the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty. Here, together with their comrades from all other faculties, students continued to construct a radical, critical position toward the society as a whole. They justified their claim for a new type of critical university linked to the working class, by disputing the role of the League of Communists as the vanguard of the working class. They claimed that the League of Communists was restoring capitalism in Yugoslavia.

Expulsion

With the growth of popularity of the General Assembly of the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty came severe attacks from high Party officials. In Tito’s second speech -to the nation he stated that there was not room in the university for extremist professors like those at the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty. Finally, on July 20, the faculty was closed by the police and the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty Committee was expelled from the League of Communists.

Social significance of the June events

With summer vacations, the chronology of events ends. The question remains: what was the significance of the June events to the various segments of Yugoslav society? The most direct and informative way of answering this question would seem to be to simply allow representatives of the segments to speak for themselves. To make this possible, we have gathered the records of conversations and discussions with peasants, workers, students, professors and party functionaries.

Peasants

A middle-aged peasant woman selling tomatoes and peaches at a large open market on the outskirts of Belgrade was asked: “What did you think of the students’ demonstrations in the city?”

Answer: “I don’t know what those city kids are up to, but God knows my life is difficult enough without kids wrecking and tearing things up in the streets. The police will knock on their doors and shoot them down in their homes, mow them down in their schools. Those children better rest easy with what they got, because there is no playing around with THEM.”

A man selling live chickens at the same market was asked if he had seen the posters calling for unity of students, workers and peasants?

Answer: “Yes, I saw a poster like that in front of that big school near the park. But I don’t pay heed to things like that. All they want is power and if they get it, they’ll be just like all the rest. Did you hear the story of the peasant kid who joined the partisans and after the revolution got a position as a communist functionary? Well anyway, he went to one of those schools and got himself graduated, got a villa on the hill, fancy furniture, big car, and a summer house on the ocean. Well, one summer he comes back to his village to see his old mother. After listening to his bragging for a while, the mother says, ‘Son, you have really done well. Live in a big house with fancy furniture. Got a big car. Even got a second house on the ocean…But son, what are you going to do when the communists come and take it all away?’”

Workers

In the evenings, workers fill the open air cafes under the large trees that line Belgrade’s wide sidewalks. Here it is easy to meet workers as they drink slivovica and live the music of Slavic romances. It is also easy to engage them in conversation–that is, so long as political problems are not discussed: “Hell, that’s politics, damn politics, that is all I need, more politics!” But this time it was different. They weren’t listening to the music; instead they were discussing.

We asked a man in his 30’s sitting alone across the table from us if he sympathized with the student demonstration. He answered, “Yes, I guess so. Sure–everyone does. But a lot of good that does them or us.”

“Did you and your fellow workers ever talk about striking?” we asked.

“Yes, we have talked about it. But most of us could not last one week without pay. I heard that three factories went on strike during the demonstration. Don’t know how they did it.”

Later we met a group of workers from a tire factory. As they were expressing loudly and openly their opinions about a certain Yugoslav leader, we asked: “Have you spoken with any students since the beginning of the events in June?”

They answered, “Sure we have. After work we went to Students’ Village. When we proved that we were not reporters they let us in. They wanted us to tell them how self-management really works. We told them that only the director and his friends self-manage the factory. Besides that, the workers’ council meetings are so damn boring that we don’t go unless we are forced to. We told the students that they had proved themselves to be part of the working class and that all us workers know it. We told them that it isn’t possible to reform this bunch of leaders that we’ve got.”

“What did they say to that?”

“They agreed!”

Students and Professors

Students of the Engineering Faculty were some of the most active during June. We recorded the following conversation with a group of students and their professor of mechanics. We asked the professor, “What is your estimate of the success of the student movement?”

Professor: “We really gave the old state a punch where it hurts. Perhaps I should not say ‘we’; the students did it all. When I arrived a few days after they had already occupied the place, I found a group of young people I didn’t know existed. It was as if they had all woken up at once. They didn’t ask; they demanded. They told me to choose their side or get out of my office. That is what I liked best! Of course I chose to work with the students. We worked together in drawing up a set of demands which were found to be very close to those drawn up by other faculties. We faced and still face difficult problems. The students must realize that as engineers they cannot begin to fathom the details of social and economic policy. They cannot butt their heads against the system; instead they must strive to make it more effective. We all agree on this now. In fact, unity in the faculty and between faculties is stronger than it has ever been before. Now students from this faculty go to meetings in other faculties.”

Student 1: What do you mean we cannot fathom the details of “social” policy? Damn it, we know what this society is all about; we live in it.

Professor: Yes, I know you have a general idea what it is all about. But the fact is your impatience shows you lack depth in economics. For instance investment policy: Can you begin to understand the sacrifices necessary for a rational investment policy?

Student 1: No. I cannot understand why a “rational” investment policy should amount to only so much unemployment. You explain that to us, prof.

Professor (laughing): It does sound absurd, doesn’t it?

Student 2: We do not understand, and I don’t think I want to understand that sort of rationality. We are naive if that’s what you mean. But you were the same when you came to power. Now you are rational and we are naive. Hell, professor, I think your rationality is shit. You’ve got a double rationality; one for yourself and one for us. You tell us that we really punched the state where it hurts to get them to double the minimum wage from 15 to 30 thousand dinars a month. Professor, I’ll bet you make from 300,000 to 400,000 a month.

Student 3: That is our first job: to keep our movement from being captured by bureaucratic hands and from adopting a bureaucratic reform. Our second job is to organize with the workers. And our third job is to achieve real autonomy for the University so that not one cop can set foot inside.

Student 4: Yes, organize with workers. In Paris they can do that. I heard that they formed groups of workers and students. But here we couldn’t begin to do that. All the factories were shut in our faces. There were police at the doors. They told the workers that we were sons of city-rich and that we were only interested in destroying the fruit of- their labor, so they would have to work harder to replace it. They even formed armed militias to attack us.

Student 1: That was the work of the communists in the factories. They told the workers that–like they tell the workers everything. Hell, I know a lot of workers that didn’t believe a word of it, but they couldn’t do a thing about it. They don’t have a single opportunity to speak. They are paid so little that they cannot afford to strike. There are so few jobs that they are afraid if they speak up they’ll get fired and never find another job. You know interviews were held for a position of doorman at Radio Belgrade. Hell, sixty university graduates applied for the job. The forced isolation of the workers, lack of voice, low pay, and lack of job security are all used by the League of Communists functionaries in the factories to divide the workers from themselves and from us and finally to control them. If you ask me, that is the real “rationality” behind what you call an “investment policy.”

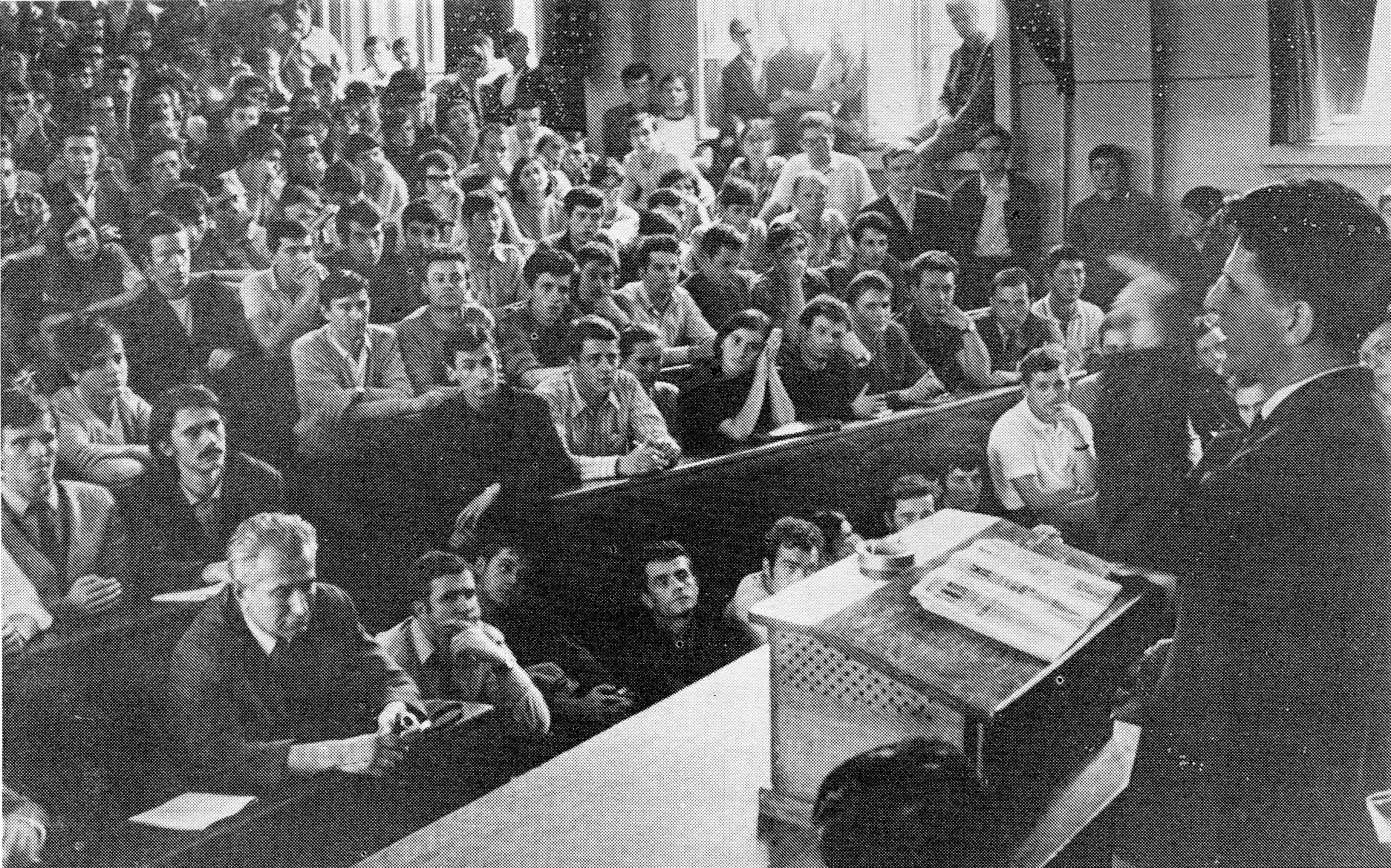

The focus of the student movement was beyond doubt located in the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty. The following is the record of a discussion held by the General Assembly of the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty on July 9th, 1968.

The General Assembly began by describing the extent of the enemy as “everyone who has something to lose through equality.” Following this, during a discussion of the enemy’s total. monopoly on the means of communication, it was noted that the most important reporter of the largest Yugoslav newspaper was present. As the reporter was one of the most vicious spokesmen for their enemy, they asked him to explain his opposition.

Reporter: Well, I’m afraid right now I can’t remember all the remarks I’ve written and as I didn’t bring any material with me…(jeering from the students)…you must realize… I’m not responsible for what is printed in the paper. The final decision is out of my hands (laughter). I guess if you like, I can give you my general opinion of what you people are doing. Essentially you are senseless agitators. You’re not going to agree with that! You believe you’ve grounds for your movement, but the fact is you are only operating out of a petit bourgeois abstract humanism.

It is true that there are deformations in our socialist society, but these problems must be examined scientifically, and so they are by all our institutions. Already many new laws have been passed to correct them. But you simply skip lightly over these difficult problems that our leaders are presently facing in order to disqualify in total everything about our socialist self-management institutions together with our leaders.

Assistant Professor: Please, would you give us a more precise definition of what you mean by “abstract humanism.”

Reporter: Abstract humanism, yes I can do that. One only has to glance at your literature to erase any doubt as to the nature of your ideology. The analysis -that you make of the real difficulties facing our society is based on a simple-minded confusion of the various social, economic and technological problems on the one hand with the nature of management of the means of production on the other. This forces you to overlook the basically socialist nature of our society and the socialist motivation of our leaders. Instead, you strike out blindly at technology, against commodity relations, and even at self-management. But out of this sort of abstraction comes nothing more than more abstraction. This is why the content of your movement is of no value, unless you consider interruption of normal social activity as being of value.

Assistant Professor: I thought you’d define abstract humanism in that way. For you, any analysis that concentrates on the interdependence of what you call “deformations” and the nature of management of the means of production is abstract, humanist, bourgeois. Of course there is no reason why we should expect that you would realize what you call abstract humanism is in reality the basis of Marxist analysis. (laughter) As a spokesman for the League, you are, of course, paid to attack Marxist social analysis.

Professor: You mentioned here, as you have often stated in your column, that we attack technology. No one among us has ever attacked technology as such. For us, the problem of technology cannot be abstracted from the level of development. In a country like ours where half the population scratch the land for a bare subsistence, where productivity of industry is so low that the vast majority of working people can hardly satisfy their basic human needs, where the problem remains to secure all children a school, and all schools teachers, where every fifth person is illiterate, and where every other person lives in a place where they don’t even have a cinema, where, for the purposes of science are invested every year less than one-half of one percent of the national income, where the scientific organization of the technological process has only just now been born; in such a backward country the time and place for an abstract attack on technology would be completely out of place.

No, our basic problem is how to conquer primitivism and backwardness. For example, socialist politics in a multi-national country cannot tolerate the process of increasing the differences between developed and backward nations. It cannot allow the creation of new sharp social differences between groups. In general, it cannot ignore the interests of the weak, the insecure, the helpless, and the underdeveloped. Further, it cannot tolerate the development of a new managerial class or any other type of bureaucratic layer above society as a whole.

But all these negative phenomena which a socialist policy could not tolerate, may serve us as a realistic description of what has been in fact happening in our country. What is more, and here is the point, all of these differences are justified by the League of Communists as the necessary consequences of maximum technological progress. When our domestic technocrats speak of the necessity for an increase in the rate of technological progress in relation to the system as a whole, they conveniently ignore all the political, social, human values for which socialism stands. Or if you like, expressed in more precise terms, they forget that the system about which they speak–that is technological progress–is only one sub-system of the global social system which includes many non-technical and non-economic variables.

Or in terms that you may understand better (addressing the reporter), we don’t attack technology, we only attack the rape of society that you justify in the name of technology. For you, democracy and human values are simply sub-headings under technological advance. For you, where technology is most advanced, there society is most advanced. For you, the United States is the most advanced society and it follows your model.

Student 1: You jump at the chance to attack our movement as non-socialist, as it attacks you and as you are by definition and membership and law a socialist, then of course we cannot be socialist –by definition (laughter). But I ask, if you stand for socialism then why have you ignored that last article by our ambassador to the United Nations on Vietnam published in your paper. In short, he said that the Viet Cong and the United States are equally guilty in Vietnam. I am insulted by that! A more reactionary view of the world revolution could not be imagined. Yet you have not jumped at the chance to attack this position. Is it because you were not paid to attack it?

Reporter: Listen, I’m a simple reporter. My powers are limited. It would have done no good to attack that article. I can’t change All our leaders’ views. I’m just a little man with little ideas.

Student 2: That sort of stuff doesn’t go with us here. We don’t rank people by their party functions, but by their contribution to society.

Reporter (angry now): I have defined for you abstract humanism in quite precise terms and you have nothing in reply but platitudes. You are now silent on commodity production; is it that you cannot defend your position?

Professor 2: Yes, you are quite right. We do attack commodity production and we find it diametrically opposed to socialism. But we may not be strong enough to move our society towards socialism. Nevertheless, we say that you are building capitalism. We demand Marxist criticism of the class you are building and the class which you represent. No, we don’t want any more of this empty so-called socialist propaganda. You have systematically divided and neutralized the power of the working class and in so doing you have created power and privilege for yourselves. What you happen to find opportunistically convenient you call socialism.

Call what you have created what you like, but don’t call it socialism. We here are for real power in the hands of the working class, and if that is the meaning of self-management, then we are for self-management. But if self-management is nothing but a facade for the construction of the competitive profit mechanism of a bureaucratic managerial–why don’t I say capitalist–class, then we are against it. No, you are not socialist and you are not creating socialism. Perhaps we have no way to stop you. But we will attempt to build a truly critical university to help the working class to understand-What you are doing in its name. Yes, you are an avant-garde, but not of the working class. Print that if you like!

From: Black & Red No3, November 1968, Detroit.