Fredy Perlman

“Heretics are always more dangerous than enemies,” concluded a Yugoslav philosopher after analyzing the repression of Marxist intellectuals by the Marxist regime of Poland. (S. Stojanovic, in Student, Belgrade, April 9, 1968, p. 7.)

In Yugoslavia, where “workers’ self-management” has become the official ideology, a new struggle for popular control has exposed the gap between the official ideology and the social relations which it claims to describe. The heretics who exposed this gap have been temporarily isolated; their struggle has been momentarily suppressed. The ideology of “self-management” continues to serve as a mask for a commercial-technocratic bureaucracy which has successfully concentrated the wealth and power created by the Yugoslav working population. However, even a single and partial removal of the mask spoils its efficacy: the ruling “elite” of Yugoslavia has been exposed; its “Marxist” proclamations have been unveiled as myths which, once unveiled, no longer serve to justify its rule.

In June 1968, the gap between theory and practice, between official proclamations and social relations, was exposed through practice, through social activity: students began to organize themselves in demonstrations and general assemblies, and the regime which proclaims self-management reacted to this rare example of popular self-organization by putting an end to it through police and press repression.

The nature of the gap between Yugoslav ideology and society had been analyzed before June 1968, not by “class enemies” of Yugoslavia’s ruling “revolutionary Marxists,” but by Yugoslav revolutionary Marxists — by heretics. According to official declarations, in a society where the working class is already in power there are no strikes, because it is absurd for workers to strike against themselves. Yet strikes, which were not reported by the press because they could not take place in Yugoslavia, have been breaking out for the past eleven years — and massively (Susret, No. 98, April 18, 1969). Furthermore, “strikes in Yugoslavia represent a symptom of the attempt to revive the workers’ movement.” In other words, in a society where workers are said to rule, the workers’ movement is dead. “This may sound paradoxical to some people. But it is no paradox due to the fact that workers’ self-management exists largely ‘on paper’…” (L. Tadic in Student, April 9, 1968, p. 7.)

Against whom do students demonstrate, against whom do workers strike, in a society where students and workers already govern themselves? The answer to this question cannot be found in declarations of the Yugoslav League of Communists, but only in critical analyses of Yugoslav social relations — analyses which are heretical because they contradict the official declarations. In capitalist societies, activities are justified in the name of progress and the national interest. In Yugoslav society, programs, policies and reforms are justified in the name of progress and the working class. However, it is not the workers who initiate the dominant projects, nor do the projects serve the workers’ interests:

“On the one hand, sections of the working class are wage-workers who live below the level necessary for existence. The burden of the economic reform is carried by the working class, a fact which must be openly admitted. On the other hand, small groups unscrupulously capitalize themselves overnight, on the basis of private labor, services, commerce, and as middlemen. Their capital is not based on their labor, but on speculation, mediation, transformation of personal labor into property relations, and often on outright corruption.” (M. Pecujlic in Student, April 30, 1968, p. 2.)

The paradox can be stated in more general terms: social relations already known to Marx reappear in a society which has experienced a socialist revolution led by a Marxist party in the name of the working class. Workers receive wages in exchange for their sold labor (even if the wages are called “personal incomes” and “bonuses”); the wages are an equivalent for the material goods necessary for the workers’ physical and social survival; the surplus labor, appropriated by state or enterprise bureaucracies and transformed into capital, returns as an alien force which determines the material and social conditions of the workers’ existence. According to official histories, Yugoslavia eliminated exploitation in 1945, when the Yugoslav League of Communists won state power. Yet workers whose surplus labor supports a state or commercial bureaucracy, whose unpaid labor turns against them as a force which does not seem to result from their own activity but from some higher power — such workers perform forced labor: they are exploited. According to official histories, Yugoslavia eliminated the bureaucracy as a social group over the working class in 1952, when the system of workers’ self-management was introduced. But workers who alienate their living activity in exchange for the means of life do not control themselves; they are controlled by those to whom they alienate their labor and its products, even if these people eliminated themselves in legal documents and proclamations.

In the United States, trusts ceased to exist legally precisely at the point in history when trusts began to centralize the enormous productive power of the U. S. working class. In Yugoslavia, the social stratum which manages the working class ceased to exist in 1952. But in actual fact, “the dismantling of the unified centralized bureaucratic monopoly led to a net of self-managing institutions in all branches of social activity (nets of workers’ councils, self-managing bodies, etc.) From a formal-legal, normative, institutional point of view, the society is self-managed. But is this also the status of real relations? Behind the self-managed facade, within the self-managed bodies, two powerful and opposed tendencies arise from the production relations. Inside of each center of decision there is a bureaucracy in a metamorphosed, decentralized form. It consists of informal groups who maintain a monopoly in the management of labor, a monopoly in the distribution of surplus labor against the workers and their interests, who appropriate on the basis of their position in the bureaucratic hierarchy and not on the basis of labor, who try to keep the representatives of ‘their’ organization, of ‘their’ region, permanently in power so as to ensure their own position and to maintain the former separation, the unqualified labor and the irrational production — transferring the burden to the workers. Among themselves they behave like the representatives of monopoly ownership… On the other hand, there is a profoundly socialist, self-governing tendency, a movement which has already begun to stir…” (Pecujlic in Ibid.)

This profoundly socialist tendency represents a struggle against the dependence and helplessness which allows workers to be exploited with the products of their own labor; it represents a struggle for control of all social activities by those who perform them. Yet what form can this struggle take in a society which already proclaims self-organization and self-control as its social, economic and legal system? What forms of revolutionary struggle can be developed in a context where a communist party already holds state power, and where this communist party has already proclaimed the end of bureaucratic rule and raised self-management to the level of an official ideology? The struggle, clearly, cannot consist of the expropriation of the capitalist class, since this expropriation has already taken place; nor can the struggle consist of the taking of state power by a revolutionary Marxist party, since such a party has already wielded state power for a quarter of a century. It is of course possible to do the thing over again, and to convince oneself that the outcome will be better the second time than the first. But the political imagination is not so poor that it need limit its perspectives to past failures. It is today realized, in Yugoslavia as elsewhere, that the expropriation of the capitalist class and its replacement by “the organization of the working class” (i.e. the Communist Party), that the taking of national-state power by “the organization of the working class” and even the official proclamation of various types of “socialism” by the Communist Party in power, are already historical realities, and that they have not meant the end of commodity production, alienated labor, forced labor, nor the beginning of popular self-organization and self-control.

Consequently, forms of organized struggle which have already proved themselves efficient instruments for the acceleration of industrialization and for rationalizing social relations in terms of the model of the Brave New World, cannot be the forms of organization of a struggle for independent and critical initiative and control on the part of the entire working population. The taking of state power by the bureau of a political party is nothing more than what the words say, even if this party calls itself “the organization of the working class,” and even if it calls its own rule “the Dictatorship of the Proletariat” or “Workers’ Self-Management.” Furthermore, Yugoslav experience does not even show that the taking of state power by the “organization of the working class” is a stage on the way toward workers’ control of social production, or even that the official proclamation of “workers’ self-management” is a stage towards its realization. The Yugoslav experiment would represent such a stage, at least historically, only in case Yugoslav workers were the first in the world to initiate a successful struggle for the de-alienation of power at all levels of social life. However, Yugoslav workers have not initiated such a struggle. As in capitalist societies, students have initiated such a struggle, and Yugoslav students were not among the first.

The conquest of state power by a political party which uses a Marxist vocabulary in order to manipulate the working class must be distinguished from another, very different historical task: the overthrow of commodity relations and the establishment of socialist relations. For over half a century, the former has been presented in the guise of the latter. The rise of a “new left” has put an end to this confusion; the revolutionary movement which is experiencing a revival on a world scale is characterized precisely by its refusal to push a party bureaucracy into state power, and by its opposition to such a bureaucracy where it is already in power.

Party ideologues argue that the “new left” in capitalist societies has nothing in common with student revolts in “socialist countries.” Such a view, at best, is exaggerated: with respect to Yugoslavia it can at most be said that the Yugoslav student movement is not as highly developed as in some capitalist countries: until June, 1968, Yugoslav students were known for their political passivity, pro-United States sympathies and petit-bourgeois life goals. However, despite the wishes of the ideologues, Yugoslav students have not remained far behind; the search for new forms of organization adequate for the tasks of socialist revolution has not remained alien to Yugoslav students. In May,1968, while a vast struggle to de-alienate all forms of separate social power was gaining historical experience in France, the topic “Students and Politics” was discussed at the Belgrade Faculty of Law. The “theme which set the tone of the discussion” was: “…the possibility for human engagement in the ‘new left’ movement which, in the words of Dr. S. Stojanovic, opposes the mythology of the ‘welfare state’ with its classical bourgeois democracy, and also the classical left parties — the social-democratic parties which have succeeded by all possible means in blunting revolutionary goals in developed Western societies, as well as the communist parties which often discredited the original ideals for which they fought, frequently losing them altogether in remarkably bureaucratic deformations.” (“The Topic is Action,” Student, May 14, 1968, p. 4.)

By May,1968, Yugoslav students had a great deal in common with their comrades in capitalist societies. A front page editorial of the Belgrade student newspaper said, “the tension of the present social-political situation is made more acute by the fact that there are no quick and easy solutions to numerous problems. Various forms of tension are visible in the University, and the lack of perspectives, the lack of solutions to numerous problems, is at the root of various forms of behavior. Feeling this, many are asking if the tension might be transformed into conflict, into a serious political crisis, and what form this crisis will take. Some think the crisis cannot be avoided, but can only be blunted, because there is no quick and efficient way to affect conditions which characterize the entire social structure, and which are the direct causes of the entire situation.” (“Signs of Political Crisis, Student, May 21, 1968, p. 1.) The same front page of the student paper carried the following quotation from Marx, on “the veiled alienation at the heart of labor”: “…Labor produces wonders for the rich, but misery for the worker. It produces palaces, but a hovel for the worker. It produces beauty, but horror for the worker. It replaces labor with machines, but throws part of the workers backward into barbarian work, and transforms the other part into machines. It produces spirit, but for the worker it produces stupidity and cretinism.”

The same month, the editorial of the Belgrade Youth Federation journal said, “…the revolutionary role of Yugoslav students, in our opinion, lies in their engagement to deal with general social problems and contradictions (among which the problems and contradictions of the social and material situation of students are included). Special student problems, no matter how drastic, cannot be solved in isolation, separate from the general social problems: the material situation of students cannot be separated from the economic situation of the society; student self-government cannot be separated from the social problems of self-government; the situation of the University from the situation of society…” (Susret, May 15, 1968). The following issue of the same publication contained a discussion on “the Conditions and the Content of Political Engagement for Youth Today” which included the following observation: “University reform is thus not possible without reform or, why not, revolutionizing of the entire society, because the university cannot be separated from the wider spectrum of social institutions. From this it follows that freedom of thought and action, namely autonomy for the University, is only possible if the entire society is transformed, and if thus transformed it makes possible a general climate of freedom and self-government.” (Susret, June 1, 1968.)

* * *

In April, 1968, like their comrades in capitalist countries, Yugoslav students demonstrated their solidarity with the Vietnamese National Liberation Front and their opposition to United States militarism. When Rudi Dutschke was shot in Berlin as a consequence of the Springer Press campaign against radical West German students, Yugoslav students demonstrated their solidarity with the German Socialist Student Federation (S.D.S.). The Belgrade student newspaper carried articles by Rudi Dutschke and by the German Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch. The experience of the world student movement was communicated to Yugoslav students. “Student revolts which have taken place in many countries this year have shown that youth are able to carry out important projects in the process of changing a society. It can be said that these revolts have influenced circles in our University, since it is obvious that courage and the will to struggle have increased, that the critical consciousness of numerous students has sharpened (revolution is often the topic of intellectual discussion).” (Student, April 23, 1968, p. 1.) As for the forms of organization through which this will to struggle could express itself, Paris provided an example. “What is completely new and extremely important in the new revolutionary movement of the Paris students — but also of German, Italian and U.S. students — is that the movement was possible only because it was independent of all existing political organizations. All of these organizations, including the Communist Party, have become part of the system; they have become integrated into the rules of the daily parliamentary game; they have hardly been willing to risk the positions they’ve already reached to throw themselves into this insanely courageous and at first glance hopeless operation.” (M. Markovic, Student, May 21, 1968.)

Another key element which contributed to the development of the Yugoslav student movement was the experience of Belgrade students with the bureaucracy of the student union. In April, students at the Philosophy Faculty composed a letter protesting the repression of Marxist intellectuals in Poland. “All over the world today, students are at the forefront in the struggle to create a human society, and thus we are profoundly surprised by the reactions of the Polish socialist regime. Free critical thought cannot be suppressed by any kind of power, not even by that which superficially leans on socialist ideals. For us, young Marxists, it is incomprehensible that today, in a socialist country, it is possible to tolerate anti-Semitic attacks and to use them for the solution of internal problems. We consider it unacceptable that after Polish socialism experienced so many painful experiences in the past, internal conflicts should be solved by such undemocratic means and that in their solution Marxist thought is persecuted. We also consider unscrupulous the attempts to separate and create conflict between the progressive student movement and the working class whose full emancipation is also the students’ goal…” (Student, April 23, 1968, p. 4.) An assembly of students at the Philosophy Faculty sent this letter to Poland — and the University Board of the Yugoslav Student Union opposed the action. Why? The philosophy students themselves analyzed the function, and the interests, of their own bureaucracy: “The University Board of the Yugoslav Student Union was in a situation in which it had lost its political nerve, it could not react, it felt weak and did not feel any obligation to do something. Yet when this body was not asked, when its advice was not heard, action ‘should not have been taken.’ This is bad tactics and still worse respect for democracy which must come to full expression in young people, like students. Precisely at the moment when the University Board had lost its understanding of the essence of the action, the discussion was channeled to the terrain of formalities: ‘Whose opinion should have been sought?’ ‘Whose permission should have been gotten?’ It wasn’t asked who would begin an action in this atmosphere of passivity. Is it not paradoxical that the University Board turns against an action which was initiated precisely by its own members and not by any forum, if we keep in mind that the basic principle of our socialism is SELF-MANAGEMENT, which means decision-making in the ranks of the members. In other words, our sin was that we applied our basic right of self-management. Organization can never be an end in itself, but only a means for the realization of ends. The greatest value of our action lies precisely in the fact that it was initiated by the rank and file, without directives or instructions from above, without crass institutionalized forms.” (Ibid.)

With these elements — an awareness of the inseparability of university problems from the social relations of a society based on alienated labor, an awareness of the experience of the international “new left,” and an awareness of the difference between self-organization by the rank and file and bureaucratic organization — the Belgrade students moved to action. The incident which set off the actions was minor. On the night of June 2, 1968, a performance which was to be held outdoors near the students’ dormitories in New Belgrade, was held in a small room indoors; students who had come to see the performance could not get in. A spontaneous demonstration began, which soon included thousands of students; the demonstrators began to walk toward the government buildings. They were stopped, as in capitalist societies, by the police (who are officially called a “militia” in the self-managed language of Yugoslavia); students were beaten by militia batons; many were arrested.

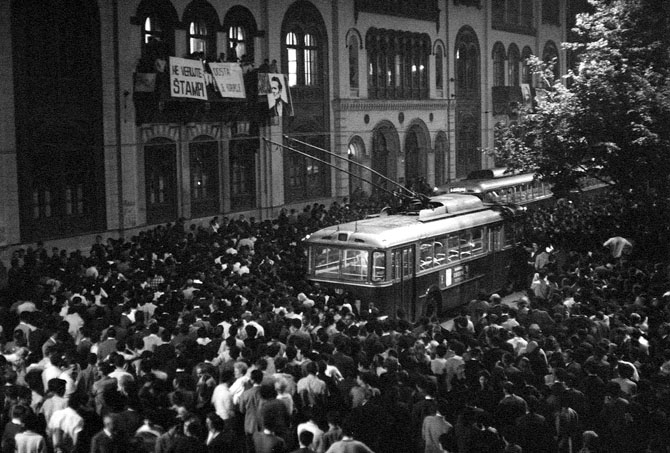

The following day, June 3, continuous general assemblies were held in most of the faculties which compose the University of Belgrade (renamed The Red University Karl Marx ), and also in the streets of New Belgrade. “In their talks students emphasized the gross social differentiation of Yugoslav society, the problem of unemployment, the increase of private property and the unearned wealth of one social layer, the unbearable condition of a large section of the working class and the need to carry out the principle of distribution according to labor consistently. The talks were interrupted by loud applause, by calls like ‘Students with Workers,’ ‘We’re sons of working people,’ ‘Down with the Socialist Bourgeoisie,’ ‘Freedom of the press and freedom to demonstrate!’” (Student, special issue, June 4, 1968, p. 1.)

Police repression was followed by press repression. The Yugoslav (Communist) press did not communicate the students’ struggle to the rest of the population. It communicated a struggle of students for student-problems, a struggle of a separate group for greater privileges, a struggle which had not taken place. The front page of the June 4 issue of Student, which was banned by Belgrade authorities, describes the attempt of the press to present a nascent revolutionary struggle as a student revolt for special privileges: “The press has once again succeeded in distorting the events at the University… According to the press, students are fighting to improve their own material conditions. Yet everyone who took part in the meetings and demonstrations knows very well that the students were already turned in another direction — toward a struggle which encompasses the general interests of our society, above all a struggle for the interests of the working class. This is why the announcements sent out by the demonstrators emphasized above all else the decrease of unjustified social differences. According to the students, this struggle (against social inequality) in addition to the struggle for relations of self-government and reform, is of central importance to the working class and to Yugoslavia today. The newspapers did not quote a single speaker who talked about unjustified social differences… The newspapers also omitted the main slogans called out during the meetings and demonstrations: For the Unity of Workers and Students, Students with Workers, and similar slogans which expressed a single idea and a single feeling: that the roads and interests of students are inseparable from those of the working class.” (Student, June 4, 1968, p. 1.)

By June 5, The Yugoslav Student Federation had succeeded in gaining leadership over the growing movement, and in becoming its spokesman. The student organization proclaimed a “Political Action Program” which contained the revolutionary goals expressed by the students in the assemblies, meetings and demonstrations — but the program also contained, as if by way of an appendix, a “Part II” on “university reform.” This appendix later played a key role in putting the newly awakened Yugoslav student movement back to sleep. Part I of the political action program emphasized social inequality first of all, unemployment, “democratization of all social and political organizations, particularly the League of Communists,” the degeneration of social property into private property, speculation in housing, commercialization of culture. Yet Part II, which was probably not even read by radical students who were satisfied with the relatively accurate expression of their goals in Part I, expresses a very different, in fact an opposite orientation. The first “demand” of Part II already presupposes that none of the goals expressed in Part I will be fulfilled: it is a demand for the adaptation of the university to the present requirements of the Yugoslav social system, namely a demand for technocratic reform which satisfies the requirements of Yugoslavia’s commercial-technocratic regime: “Immediate reform of the school system to adapt it to the requirements of the social and cultural development of our economy and our self-management relations…” (Student, special issue, June 8, 1968, pp. 1–2.)

This crude reversal, this manipulation of the student revolt so as to make it serve the requirements of the dominant social relations against which the students had revolted, did not become evident until the following school year. The immediate reactions of the regime were far less subtle: they consisted of repression, isolation, separation. The forms of police repression included beatings and jailings, a ban on the student newspaper which carried the only complete report of the events, demonstrations and meetings, and on the night of June 6, “two agents of the secret police and a militia officer brutally attacked students distributing the student paper, grabbed 600 copies of the paper, tore them to pieces and burned them. All this took place in front of a large group of citizens who had gathered to receive copies of the paper.” (Student, June 8, 1968, p. 3.)

In addition to police repression, the dominant interests succeeded in isolating and separating the students from the workers, they temporarily succeeded in their “unscrupulous attempt to separate and create conflict between the progressive student movement and the working class whose full emancipation is also the students’ goal.” This was done in numerous ways. The ban on the student press and misreporting by the official press kept workers ignorant of the students’ goals; enterprise directors and their circles of experts “explained” the student struggle to “their” workers, instructed workers to defend “their” factories from attacks by “violent” students, and then sent letters to the press, in the name of the “workers’ collective,” congratulating the police for saving Yugoslav self-management from the violent students. “According to what is written and said, it turns out that it was the students who used force on the National Militia, that they blocked militia stations and surrounded them. Everything which has characterized the student movement from the beginning, in the city and in the university buildings, the order and self-control, is described with the old word: violence… This bureaucracy, which wants to create a conflict between workers and students, is inside the League of Communists, in the enterprises and in the state offices, and it is particularly powerful in the press (the press is an outstandingly hierarchic structure which leans on self-management only to protect itself from critiques and from responsibility). Facing the workers’ and students’ movement, the bureaucracy feels that it’s losing the ground from under its feet, that it’s losing those dark places where it prefers to move — and in fear cries out its meaningless claims…. Our movement urgently needs to tie itself with the working class. It has to explain its basic principles, and it has to ensure that these principles are realized, that they become richer and more complex, that they don’t remain mere slogans. But this is precisely what the bureaucracy fears, and this is why they instruct workers to protect the factories from students, this is why they say that students are destroying the factories. What a monumental idiocy!” (D. Vukovic in Student, June 8, 1968, p. 1) Thus the self-managed directors of Yugoslav socialism protected Yugoslav workers from Yugoslav students just as, a few weeks earlier, the French “workers’ organizations” (the General Federation of Labor and the French Communist Party) had protected French workers from socialist revolution.

* * *

Repression and separation did not put an end to the Yugoslav revolutionary movement. General assemblies continued to take place, students continued to look for forms of organization which could unite them with workers, and which were adequate for the task of transforming society. The third step was to pacify and, if possible, to recuperate the movement so as to make it serve the needs of the very structure it had fought against. This step took the form of a major speech by Tito, printed in the June 11 issue of Student. In a society in which the vast majority of people consider the “cult of personality” in China the greatest sin on earth, the vast majority of students applauded the following words of the man whose picture has decorated all Yugoslav public institutions, many private houses, and most front pages of daily newspapers for a quarter of a century: “…Thinking about the demonstrations and what preceded them, I have reached the conclusion that the revolt of the young people, of the students, rose spontaneously. However, as the demonstrations developed and when later they were transferred from the street to university auditoriums, a certain infiltration gradually took place on the part of foreign elements who wanted to use this situation for their own purposes. These include various tendencies and elements, from the most reactionary to the most extreme, seemingly radical elements who hold parts of Mao Tse Tung’s theories.” After this attempt to isolate and separate revolutionary students by shifting the problem from the content of the ideas to the source of the ideas (foreign elements with foreign ideas), the President of the Republic tries to recuperate the good, domestic students who only have local ideas. “However, I’ve come to the conclusion that the vast majority of students, I can say 90%, are honest youth… The newest developments at the universities have shown that 90% of the students are our socialist youth, who do not let themselves be poisoned, who do not allow the various Djilasites, Rankovicites, Mao-Tse-Tungites realize their own goals on the pretext that they’re concerned about the students… Our youth are good, but we have to devote more attention to them.” Having told students how they should not allow themselves to be used, the President of Self-Managed Yugoslavia tells them how they should allow themselves to be used. “I turn, comrades and workers, to our students, so that they’ll help us in a constructive approach and solution of all these problems. May they follow what we’re doing, that is their right; may they take part in our daily life, and when anything is not clear, when anything has to be cleared up, may they come to me. They can send a delegation.” As for the content of the struggle, its goals, Tito speaks to kindergarten children and promises them that he will personally attend to every single one of their complaints. “…The revolt is partly a result of the fact that the students saw that I myself have often asked these questions, and even so they have remained unsolved. This time I promise students that I will engage myself on all sides to solve them, and in this students must help me. Furthermore, if I’m not able to solve these problems then I should no longer be on this place. I think that every old communist who has the consciousness of a communist should not insist on staying where he is, but should give his place to people who are able to solve problems. And finally I turn to students once again: it’s time to return to your studies, it’s time for tests, and I wish you success. It would really be a shame if you wasted still more time.” (Tito in Student, June 11, 1968, pp. 1–2.)

This speech, which in itself represents a self-exposure, left open only two courses of action: either a further development of the movement completely outside of the clearly exposed political organizations, or else co-optation and temporary silence. The Yugoslav movement was co-opted and temporarily silenced. Six months after the explosion, in December, the Belgrade Student Union officially adopted the political action program proclaimed in June. This version of the program included a Part I, on the social goals of the struggle, a Part II, on university reform, and a newly added Part III, on steps to be taken. In Part III it is explained that, “in realizing the program the method of work has to be kept in mind. 1) The Student Union is not able to participate directly in the solution of the general social problems (Part I of the program)… 2) The Student Union is able to participate directly in the struggle to reform the University and the system of higher education as a whole (Part II of the program), and to be the spokesman of progressive trends in the University.” (Student, December 17, 1969, p. 3.) Thus several events have taken place since June. The students’ struggle has been institutionalized: it has been taken over by the “students’ organization.” Secondly, two new elements have been appended to the original goals of the June struggle: a program of university reform, and a method for realizing the goals. And, finally, the initial goals of the struggle are abandoned to the social groups against whom the students had revolted. What was once an appendix has now become the only part of the program on which students are to act: “university reform.” Thus the revolt against the managerial elite has been cynically turned into its opposite: the university is to be adapted to serve the needs of the dominant system of social relations; students are to be trained to serve the managerial elite more effectively.

While the “students’ organization” initiates the “struggle” for university reform, the students, who had begun to organize themselves to struggle for very different goals, once again become passive and politically indifferent. “June was characterized by a burst of consciousness among the students; the period after June in many ways has the characteristics of the period before June, which can be explained by the inadequate reaction of society to the June events and to the goals expressed in June.” (Student, May 13, 1969, P. 4.)

The struggle to overthrow the status quo has been turned away from its insanity; it has been made realistic; it has been transformed into a struggle to serve the status quo. This struggle, which the students do not engage in because “their organization” has assumed the task of managing it for them, is not accompanied by meetings, general assemblies or any other form of self-organization. This is because the students had not fought for “university reform” before June or during June, and they do not become recuperated for this “struggle” after June. It is in fact mainly the “students’ spokesmen” who have become recuperated, because what was known before June is still known after June: “Improvement of the University makes sense only if it is based on the axiom that transformations of the university depend on transformations of the society. The present condition of the University reflects, to a greater or lesser extent, the condition of the society. In the light of this fact, it is meaningless to hold that we’ve argued about general social problems long enough, and that the time has come to turn our attention to university reform.” (B. Jaksic in Susret, February 19, 1969.)

The content of “university reform” is defined by the Rector of the University of Belgrade. In his formulation, published in Student half a year after the June events, the Rector even includes “goals” which the students had specifically fought against, such as separation from the working class for a price, and the systematic integration of students, not only into the technocracy, but into the armed forces as well: “The struggle to improve the material position of the university and of students is our constant task… One of the key questions of present-day work at the university is the imperative to struggle against all forms of defeatism and demagogy. Our university, and particularly our student youth, are and will be the enthusiastic and sure defense of our socialist homeland. Systematic organization in the building of the defensive power of our country against every aggressor, from whatever side he may try to attack us, must be the constant, quick and efficient work of all of us.” (D. Ivanovic in Student, October 15, 1968, p. 4.) These remarks were preceded by long and very abstract statements to the effect that “self-management is the content of university reform.” The more specific remarks quoted above make it clear what the Rector understands to be the “content” of “self-management.”

Since students do not eagerly throw themselves into the “struggle” for university reform, the task is left to the experts who are interested in it, the professors and the academic functionaries. “The main topics of conversation of a large number of teachers and their colleagues are automobiles, weekend houses and the easy life. These are also the main topics of conversation of the social elite which is so sharply criticized in the writings of these academics who do not grasp that they are an integral and not unimportant part of this elite.” (B. Jaksic in Susret, February 19, 1969.)

Under the heading of University reform, one of Yugoslavia’s leading (official) economists advocates a bureaucratic utopia with elements of magic. The same economist who, some years ago, had emphasized the arithmetical “balances of national production” developed by Soviet “social engineers” for application on human beings by a state bureaucracy, now advocates “the application of General Systems Theory for the analysis of concrete social systems.” This General Systems Theory is the latest scientific discovery of “developed and progressive social systems” — like the United States. Due to this fact, “General Systems Theory has become indispensable for all future experts in fields of social science, and also for all other experts, whatever domain of social development they may participate in.” (R. Stojanovic, “On the Need to Study General Systems Theory at Social Science Faculties,” Student, February 25, 1969.) If, through university reform, General Systems Theory can be drilled into the heads of all future Yugoslav technocrats, presumably Yugoslavia will magically become a “developed and progressive social system” — namely a commercial, technocratic and military bureaucracy, a wonderland for human engineering.

* * *

The students have been separated from the workers; their struggle has been recuperated: it has become an occasion for academic bureaucrats to serve the commercial-technocratic elite more effectively. The bureaucrats encourage students to “self-manage” this “university reform,” to participate in shaping themselves into businessmen, technicians and managers. Meanwhile, Yugoslav workers produce more than they’ve ever produced before, and watch the products of their labor increase the wealth and power of other social groups, groups which use that power against the workers. According to the Constitution, the workers govern themselves. However, according to a worker interviewed by Student, “That’s only on paper. When the managers choose their people, workers have to obey; that’s how it is here.” (Student, March 4, 1969, p. 4.) If a worker wants to initiate a struggle against the continually increasing social inequality of wealth and power, he is checked by Yugoslavia’s enormous unemployment: a vast reserve army of unemployed waits to replace him, because the only alternative is to leave Yugoslavia. The workers still have a powerful instrument with which to “govern themselves”; it is the same instrument workers have in capitalist societies: the strike. However, according to one analyst, strikes of workers who are separated from the revolutionary currents of the society and separated from the rest of the working class, namely “economic” strikes, have not increased the power of workers in Yugoslav society; the effect is nearly the opposite: “What has changed after eleven years of experience with strikes? Wherever they broke out, strikes reproduced precisely those relations which had led to strikes. For example, workers rebel because they’re shortchanged in the distribution; then someone, probably the one who previously shortchanged them, gives them what he had taken from them; the strike ends and the workers continue to be hired laborers. And the one who gave in did so in order to maintain his position as the one who gives, the one who saves the workers. In other words, relations of wage-labor, which are in fact the main cause of the strike as a method for resolving conflicts, continue to be reproduced. This leads to another question: is it at all possible for the working class to emancipate itself in a full sense within the context of an enterprise, or is that a process which has to develop on the level of the entire society, a process which does not tolerate any separation between different enterprises, branches, republics?” (Susret, April 18, 1969.)

As for the experts who shortchange the working class, Student carried a long description of various forms of expertise: “1) Enterprise functionaries (directors, businessmen, traveling salesmen, etc.) are paid by the managing board, the workers’ council or other self-managed organs, for breaking legal statutes or moral norms in ways that are economically advantageous to the enterprise… 2)… 3) Fictitious or simulated jobs are performed for purposes of tax evasion… 4)… 5) Funds set aside for social consumption are given out for the construction of private apartments, weekend houses, or for the purchase of automobiles…” (Student, February 18, 1969, p. 1.)

The official ideology of Socialist Yugoslavia does not conflict with the interests of its commercial-technocratic elite; in fact it provides a justification for those interests. In March,1969, the Resolution of the Ninth Congress of the Yugoslav League of Communists referred to critiques by June revolutionaries only to reject them, and to reaffirm the official ideology. The absurd contention according to which commodity production remains the central social relation in “socialism” is restated in this document. “The economic laws of commodity production in socialism act as a powerful support to the development of modern productive forces and rational management.” This statement is justified by means of the now-familiar demonology, namely by the argument that the only alternative to commodity production in “socialism” is Stalin: “Administrative-bureaucratic management of administration and social reproduction deforms real relations and forms monopolies, namely bureaucratic subjectivism in the conditions of management, and unavoidably leads to irrationality and parasitism in the distribution of the social product…” Thus the choice is clear: either maintain the status quo, or else return to the system which the same League of Communists had imposed on Yugoslav society before 1948. The same type of demonology is used to demolish the idea that “to each according to his work,” the official slogan of Yugoslavia, means what the words say. Such an interpretation “ignores differences in abilities and contributions. Such a demand leads to the formation of an all-powerful administrative, bureaucratic force, above production and above society; a force which institutes artificial and superficial equalization, and whose power leads to need, inequality and privilege…” (Student, March 18, 1969.) The principle “to each according to his work” was historically developed by the capitalist class in its struggle against the landed aristocracy, and in present day Yugoslavia this principle has the same meaning that it had for the bourgeoisie. Thus the enormous personal income (and bonuses) of a successful commercial entrepreneur in a Yugoslav import-export firm is justified with this slogan, since his financial success proves both his superior ability as well as the value of his contribution to society. In other words, distribution takes place in terms of the social evaluation of one’s labor, and in a commodity economy labor is evaluated on the market. The result is a system of distribution which can be summarized by the slogan “from each according to his ability, to each according to his market success,” a slogan which describes a system of social relations widely known as capitalist commodity production, and not as socialism (which was defined by Marx as the negation of capitalist commodity production).

The defense of this document was not characterized by more subtle methods of argument, but rather by the type of conservative complacency which simply takes the status quo for granted as the best of all possible worlds. “I can hardly accept critiques which are not consistent with the spirit of this material and with the basic ideas which it really contains… Insistence on a conception which would give rational solutions to all the relations and problems we confront, seems to me to go beyond the real possibilities of our society… This is our reality. The different conditions of work in individual enterprises, in individual branches, in individual regions of the country and elsewhere — we cannot eliminate them…” (V. Rakic in Student, March 11, 1969, p. 12.)

In another issue of Student, this type of posture was characterized in the following terms: “A subject who judges everything consistent and radical as an exaggeration identifies himself with what objectively exists; thus everything seems to him too idealistic, abstract, Quixotic, unreal, too far-fetched for our reality, and never for him. Numerous people, particularly those who could contribute to the transformation of society, continually lean on reality, on the obstacles which it presents, not seeing that often it is precisely they, with their superficial sense for reality, with their so-called real-politik, who are themselves the obstacles whose victims they claim to be.” (D. Grlic in Student, April 28, 1969, p. 3.)

“We cannot allow ourselves to forget that democracy (not to speak of socialism) as well as self-government in an alienated and ideological form, may become a dangerous instrument for promulgating and spreading the illusion that by ‘introducing’ it, namely through a proclamation, a decree on self-management, we’ve chosen the right to independent control, which eo ipso negates the need for any kind of struggle. Against whom, and why should we struggle when we already govern ourselves; now we are ourselves — and not anyone above us — guilty for all our shortcomings.” (Ibid.)

The socialist ideology of Yugoslavia has been shown to be hollow; the ruling elite has been deprived of its justifications. But as yet the exposure has taken the form of critical analysis, of revolutionary theory. Revolutionary practice, self-organization by the base, as yet has little experience. In the meantime, those whose struggle for socialism has long ago become a struggle to keep themselves in power, continue to identify their own rule with self-government of the working class, they continue to define the commodity economy whose ideologues they have become as the world’s most democratic society. In May 1969, the newly elected president of the Croatian parliament, long-time member of the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party, blandly stated that “the facts about the most basic indexes of our development show and prove that the economic development of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, and of Yugoslavia as a whole, has been harmonious and progressive.” The president is aware of unemployment and the forced exile of Yugoslav workers, but the problem is about to be solved because “Some actions have been initiated to deal with the concern over our people who are temporarily employed abroad; these actions must be systematized, improved, and included as an integral part of our system, our economy and our polity…” The president is also aware of profound critiques of the present arrangement, and for him these are “illusions, confusions, desperation, impatience, Quixotic pretensions which are manifested — regardless of the seeming contradiction — from leftist revolutionary phrases to chauvinistic trends which take the form of philosophy, philology, movement of the labor force, economic situation of the nation, republic, etc… We must energetically reject attempts to dramatize and generalize certain facts which, pulled out of the context of our entire development and our reality, attempt to use them for defeatist, demoralizing, and at times chauvinistic actions. We must systematically and factually inform our working people of these attempts, we must point out their elements, their methods, their real intentions, and the meaning of the actions.” (J. Blazevic, Vjesnik, May 9, 1969, p. 2.)

Official reactions to the birth of the Yugoslav “new left,” from those of the President of Yugoslavia to those of the President of Croatia, are humorously summarized in a satire published on the front page of the May 13 issue of Student. “…Many of our opponents declare themselves for democracy, but what they want is some kind of pure or full democracy, some kind of libertarianism. In actual fact they’re fighting for their own positions, so as to be able to speak and work according to their own will and the way they think right. We reject all the attempts of these anti-democratic forces; in our society it must be clear to everyone who is responsible to whom… In the struggle against these opponents, we’re not going to use undemocratic means unless democratic means do not show adequate success. An excellent example of the application of democratic methods of struggle is our confrontation with bureaucratic forces. We all know that in the recent past, bureaucracy was our greatest social evil. And where is that bureaucracy now? It melted, like snow. Under the pressure of our self-managing mechanisms and our democratic forces, it melted all by itself, automatically, and we did not even need to make any changes whatever in the personnel or the structures of our national government, which in any case would not have been consistent with self-management. The opponents attack our large social differences, and they even call them unjustified… But the working class, the leading and ruling force of our society, the carrier of progressive trends and the historical subject, must not become privileged at the expense of other social categories; it must be ready to sacrifice in the name of the further construction of our system. The working class is aware of this and decisively rejects all demands for a radical decrease in social differences, since these are in essence demands for equalization; and this, above all else, would lead to a society of poor people. But our goal is a society in which everyone will be rich and will get according to his needs… The problem of unemployment is also constantly attacked by enemy forces. Opponents of our system argue that we should not make such a fuss about creating new jobs (as if that was as easy as opening windows in June), and that trained young people would accelerate the economic reform… In the current phase of our development we were not able to create more jobs, but we created another type of solution — we opened our frontiers and allowed our workers free employment abroad. Obviously it would be nice if we all had work here, at home. Even the Constitution says that. But that cannot be harmonized with the new phase of our reform. However, the struggle for reform has entered its final, conclusive stage and things will improve significantly. In actual fact, our people don’t have it so bad even now. Earlier they could work only for one state, now they can work for the entire world. What’s one state to the entire world? This creates mutual understanding and friendship… We were obviously unable to describe all the enemies of our system, such as various extremists, leftists, rightists, anarcho-liberals, radicals, demagogues, teachers, dogmatics, would-be-revolutionaries (who go so far as to claim that our revolution has fallen into crisis), anti-reformists and informal groups…, unitarians, folklorists, and many other elements. All of them represent potential hotbeds of crisis. All these informal groups and extremists must be energetically isolated from society, and if possible re-formed so as to prevent their destructive activity.” (V. Teofilovic in Student, May 13, 1969, p. 1.)

The Yugoslav experience adds new elements to the experience of the world revolutionary movement; the appearance of these elements has made it clear that socialist revolution is not a historical fact in Yugoslavia’s past, but a struggle in the future. This struggle has been initiated, but it has nowhere been carried out. “For as Babeuf wrote, managers organize a revolution in order to manage, but an authentic revolution is only possible from the bottom, as a mass movement. Society, all of its spontaneous human activity, rises as a historical subject and creates the identity of politics and popular will which is the basis for the elimination of politics as a form of human alienation.” (M. Vojnovic in Student, April 22, 1969, p. 1.) Revolution in this sense cannot even be conceived within the confines of a single university, a single factory, a single nation-state. Furthermore, revolution is not the repetition of an event which already took place, somewhere, sometime; it is not the reproduction of past relations, but the creation of new ones. In the words of another Yugoslav writer, “it is not only a conflict between production and creation, but in a larger sense — and here I have in mind the West as well as the East — between routine and adventure.” (M. Krleza in Politika, December 29, 1968; quoted in Student, January 7, 1969.)

Crikvenica

May, 1969.